This Week in China’s History: May 20, 1645

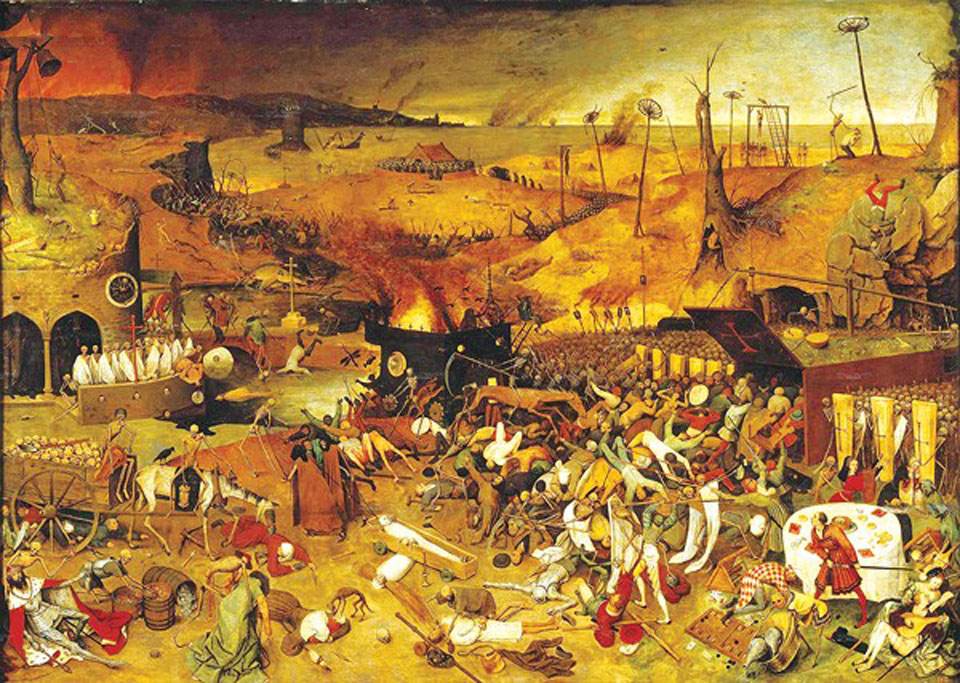

“The ground was stained with blood and covered with mutilated and dismembered bodies. Every gutter and pond was filled with corpses lying one upon the other.” This was the scene in Yangzhou in the spring of 1645, as the Manchu conquest of China took a grisly turn.

In her book on the city’s history, Speaking of Yangzhou, historian Antonia Finnane describes Yangzhou, in the Yangtze Delta, as evoking “images of artists, men of letters, great merchant families, waterways, an urban environment of considerable charm, a past imbued with color and romance.” Less well-known today than neighbors like Hangzhou, Suzhou, or Nanjing, Yangzhou was among the most beautiful and sophisticated of cities in late Imperial China, famous especially for the poetry and painting its denizens produced.

Yangzhou has ancient roots. It was one of the provinces mentioned in classical texts like The Rites of Zhou and became a regional capital in the Sui dynasty. At that same time, the completion of the Grand Canal, linking the north and south, made Yangzhou a port city — where goods could move between the canal and the Yangtze River — and one of the most important commercial centers in China. In the Tang, the city was home to a large community of Arab merchants (more about that in another column). Yangzhou was briefly the capital of the Song dynasty, after Kaifeng fell to the Jurchens in 1126, and under the Mongol Yuan dynasty it seems to have been an international city, with a community of Italian merchants, including one Marco Polo, who claimed to have served as its governor (though the claim is hard to substantiate).

It was under the Ming that Yangzhou reached its greatest prominence. Five and half miles of walls surrounded the city, which remained a flourishing commercial center right through the end of the dynasty.

This column has focused several times on different aspects of the Ming fall and Qing conquest. Even after Lǐ Zìchéng’s 李自成 capture of Beijing, the last Ming emperor’s suicide, and the battles and bargains of Wú Sānguì 吳三桂, the collapse of the Ming and its replacement by the Manchus was far from orderly or certain. A rump Ming court established itself in Nanjing, hoping to keep southern China from the Manchus and to rule as the Southern Ming. As the Manchu invasion moved inexorably south, Yangzhou, just a few miles from the new capital, found itself in the crosshairs.

The Southern Ming court at Nanjing viewed Yangzhou as essential, and Shǐ Kěfǎ 史可法, the minister of war, coordinated the city’s defenses personally. By mid-May, the Manchu armies had arrived at the city’s gates, and began a siege. For a week, the Manchu commander, Dodo, sought Shi Kefa’s surrender. He sent Li Yuchun, a former Ming official who had gone over to the Qing, to implore Shi to change sides, offering not only riches and prestige, but the chance to shape policy and guide conduct in the new empire. Unpersuaded, Shi Kefa instead drew an arrow and shot the messenger dead, offering his own take on the wages of collaboration. A series of messengers, with similar offers, followed, meeting similar fates.

Rebuked by his adversary, Dodo began the assault on May 20. For a time, the Ming defenders held their positions, relying on cannons mounted atop the city walls to rain artillery down on the Manchu attackers, but the respite was brief.

As Frederic Wakeman records in the epic history of the Qing conquest, The Great Enterprise, “Dodo had ordered his men to take [Yangzhou] whatever the cost, and as each Qing infantryman was struck down by an arrow, another took his place. Soon the corpses were piled so high that some of the attackers did not even need ladders to scale the walls.” Once inside, Qing troops opened the city walls and soldiers streamed in. Contemporary accounts record happened next: “All was chaos…soldiers descending from the city walls, victors with bows and swords pursuing the vanquished….Before nightfall, a great massacre had commenced.”

Lynn Struve, who has collected primary sources of the conquest in her essential China in Tigers’ Jaws, translates the desperation of one survivor, Wang Xiuchu: “By dusk, the sound of Qing soldiers slaying people had penetrated to the doorstep, so we climbed onto the roof for temporary refuge. The rain was heavy…every strand of our hair got soaked. The sounds of lamentation and pain outside struck terror from the ears to the soul.”

The slaughter went on for six days. Collaborators and informants were accused of leading Qing troops to find families in hiding or trying to flee. Puddles and streams ran red. As Wakeman put it, “Yangzhou was transformed into a charnel house, reeking of blood and strewn with mutilated bodies.” Contemporary accounts put the death toll at 800,000.

Wakeman notes reasons to view this number skeptically. Estimates place the population of the entire prefecture at around 1 million. Finnane goes further, calling the 800,000 figure “impossibly large,” and estimates that the city held no more than 175,000 people at the time. Historian Zhang Defang guesses that only 20,000 to 30,000 residents were in Yangzhou — considering the overall population and the threat posed by the Manchus — at the time of the attack, though others dispute this as low. And in any case, there were soldiers and refugees in the city besides its permanent population.

In Finnane’s view, the number of deaths is both besides the point and exactly the point, depending on the question being asked. The large, round figure need not be literally accurate to convey the trauma the city and its residents endured. Bodies — and body parts — were piled in the streets. Every family lost members. For days after the massacre, smoke rose from piles of burning corpses. Whether it was 8,000 or 80,000 or 800,000, the city was transformed by the violence.

Finnane’s other point, though, was that the massacre was not quite the cataclysm the numbers suggest. “The depiction of carnage in Wang Xiuchu’s diary,” she writes, “leaves [the impression] of a city laid waste…such that a long period of convalescing might well be imagined as necessary to its recovery.” A close reading of the diary — and the fact of its publication a decade after the massacre — suggests that the city endured a devastating trial, but that it recovered quickly, rebounding to flourish once again within a relatively short period of time.

The memory of Yangzhou came to be as important as the massacre itself. Writing in the journal History and Memory, Peter Zarrow illustrates the way late Qing nationalists, including Sun Yat-sen (孙中山 Sūn Zhōngshān), Zōu Róng 邹容, and Zhāng Bǐnglín 章炳麟, used the events of 1645 to fuel their nationalist movements through “anti-Manchuism and memories of atrocity.” At a time when Qing weakness was undeniable, the notion that Manchu rule had undermined China’s greatness was a powerful narrative, and charges of atrocity were a powerful message for building revolutionary fervor.

In the 20th century, the events at Yangzhou were given another meaning: as Japanese armies occupied Jiangnan, some pointed to the actions of collaborators in Yangzhou to see the city as treasonous and untrustworthy, as though the actions of the 1640s presaged those of the 1940s.

Whatever the numbers, it’s vital that we remember the victims of past wars — including the massacre at Yangzhou — so that we might, somehow, find a way to prevent such atrocities from recurring.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.