This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

Sometimes items of exceptional historical value sit unregarded under our noses. One day, when Jakob Moritz Becker was helping his grandmother declutter her house, they stumbled across something remarkable: a collection of about 300 photographs of China taken by her father and his great-grandfather Horst Köntopp during a trip to the country in 1961. Becker already knew about this collection as a kid and had already seen some photographs, but it was only later, when facing the decision of whether they should keep or discard them, that he realized the value of what they had in their hands.

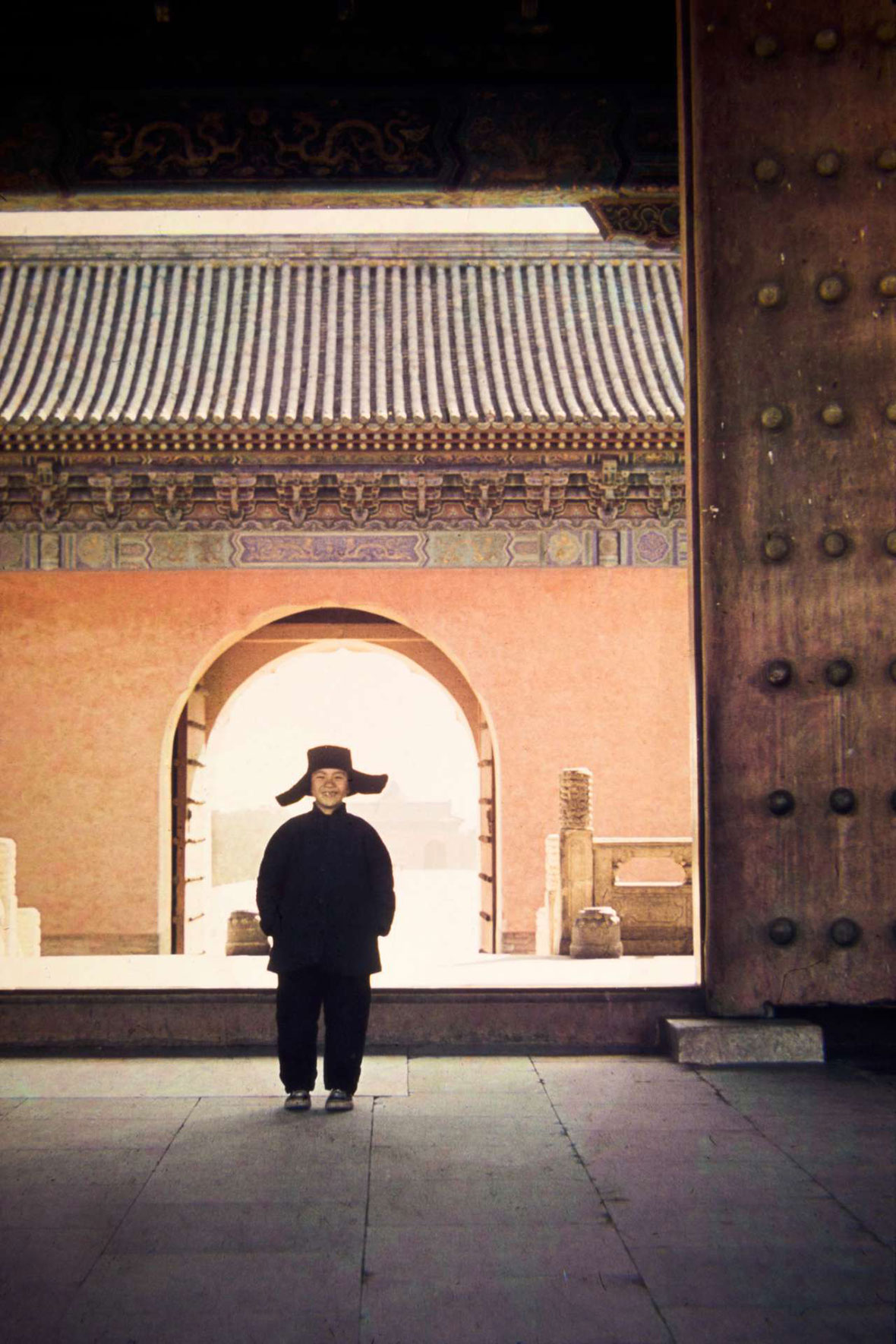

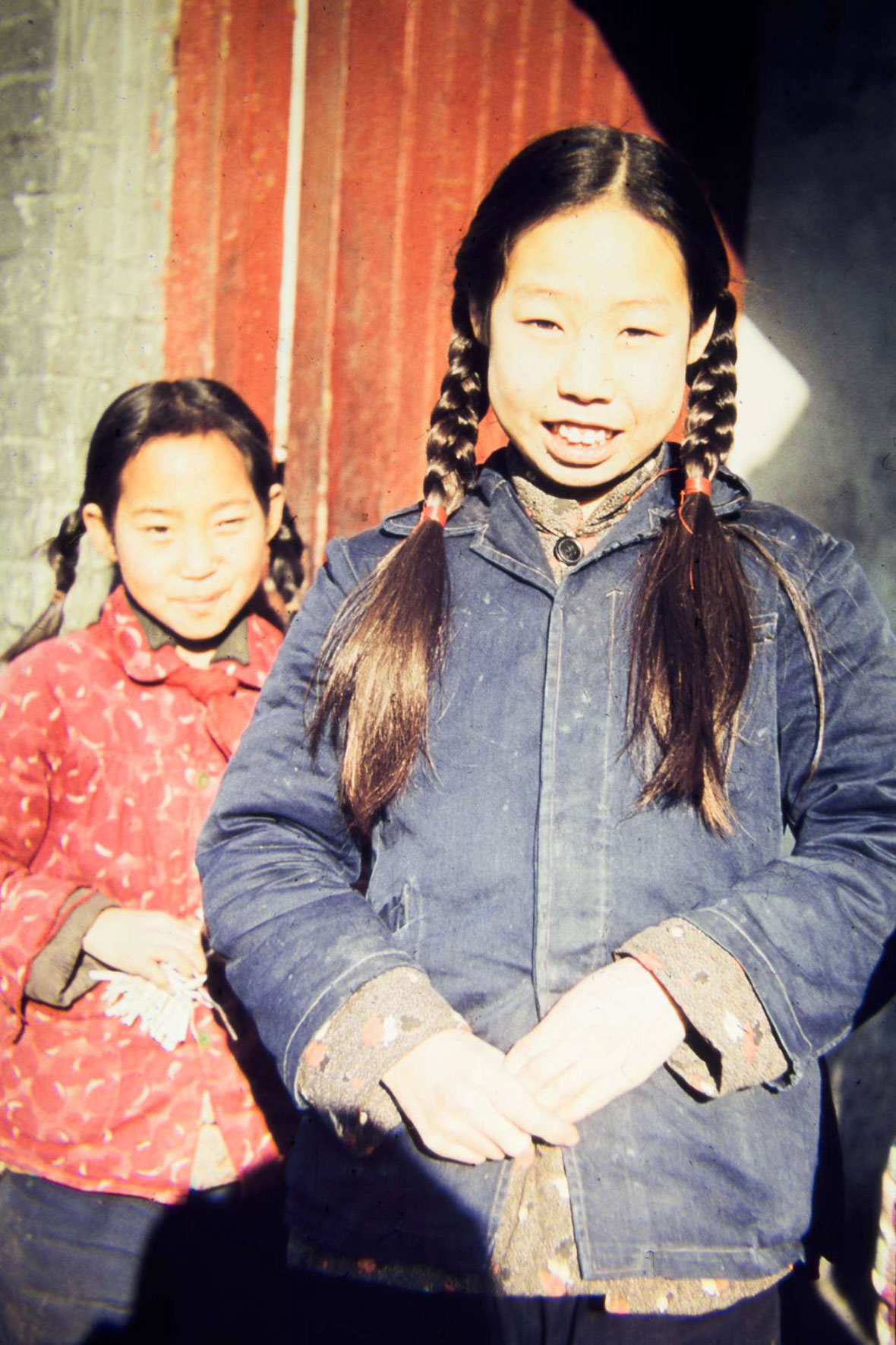

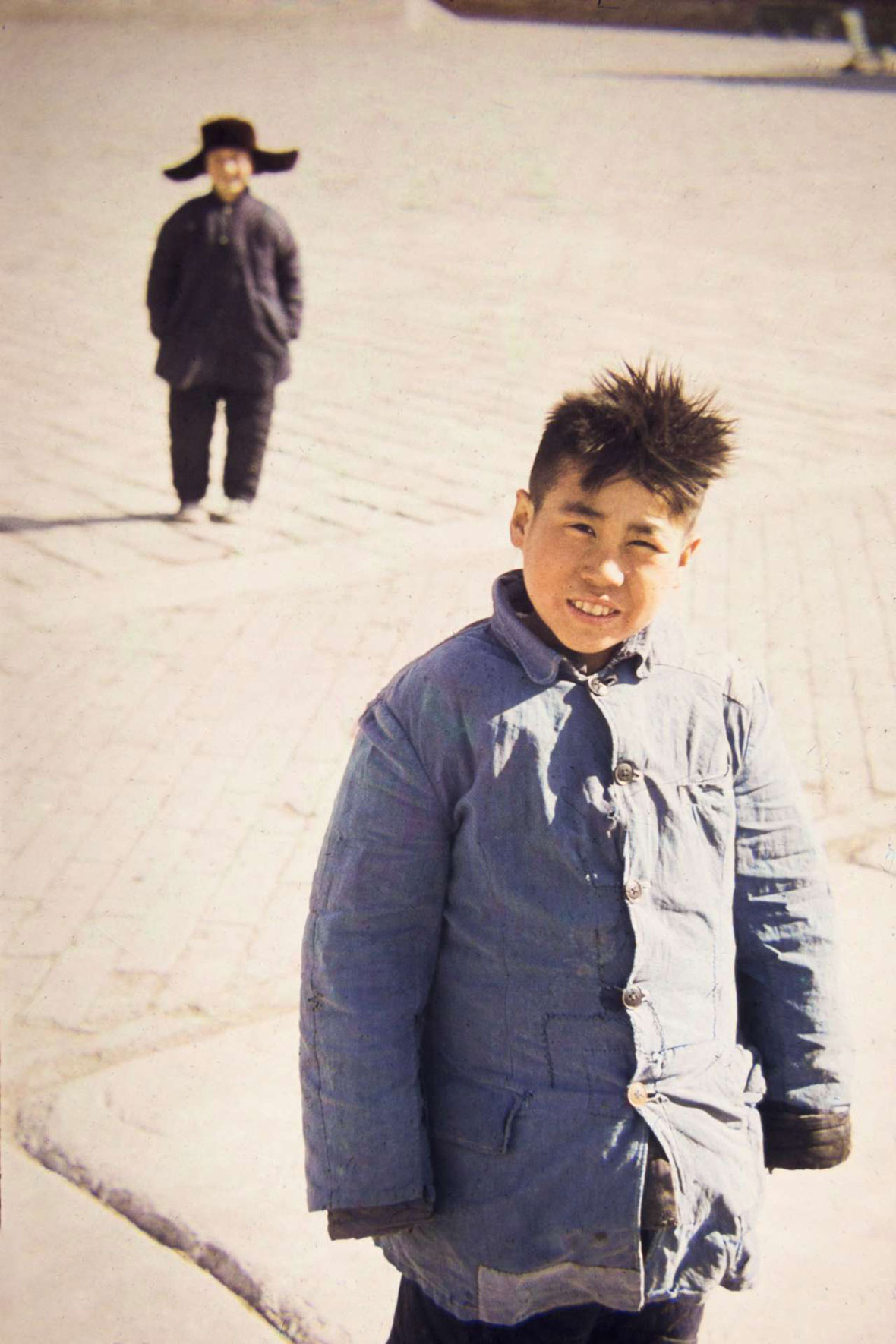

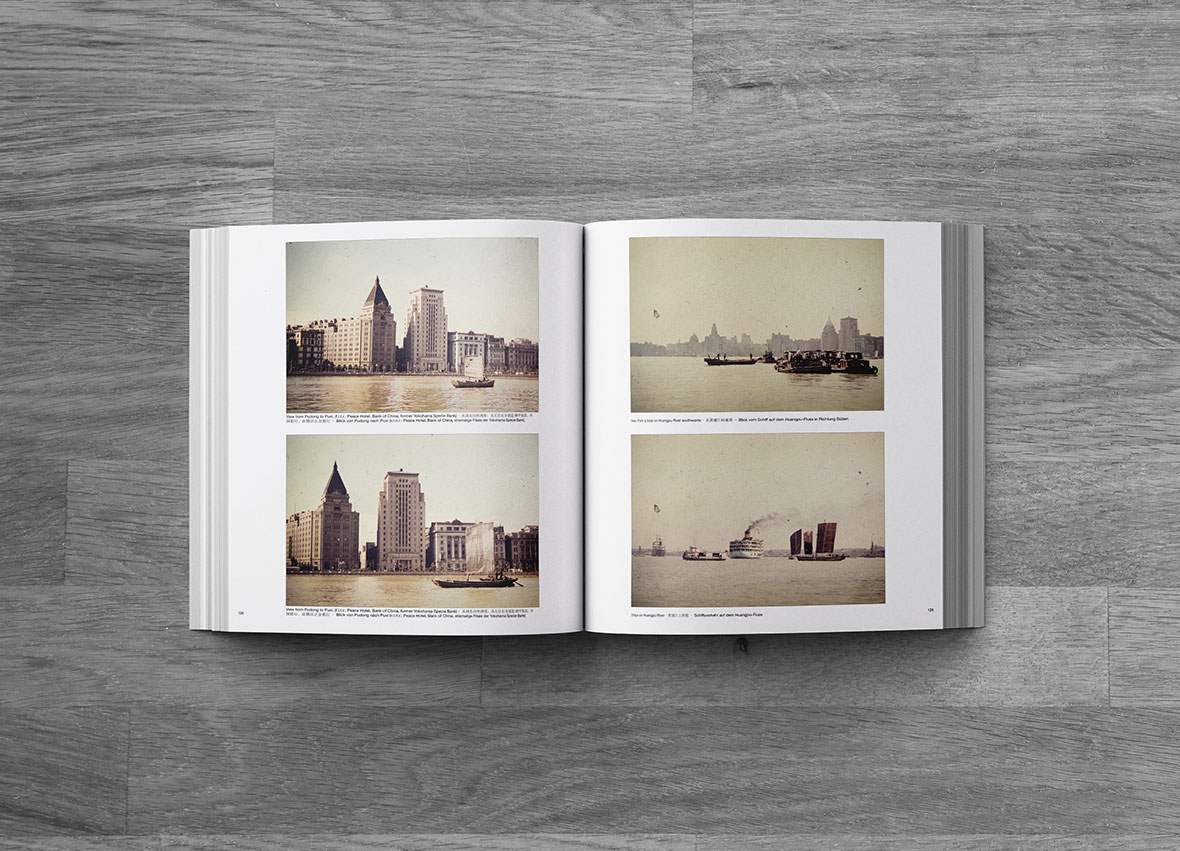

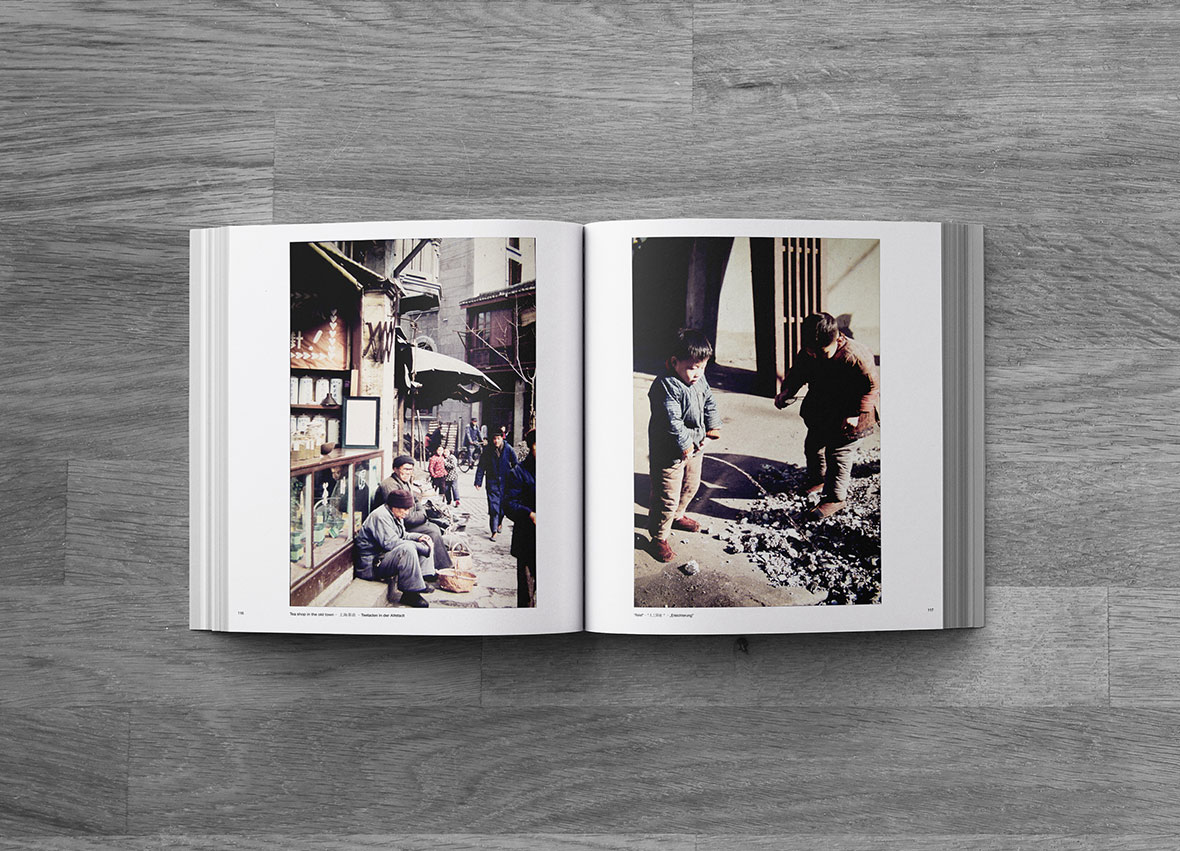

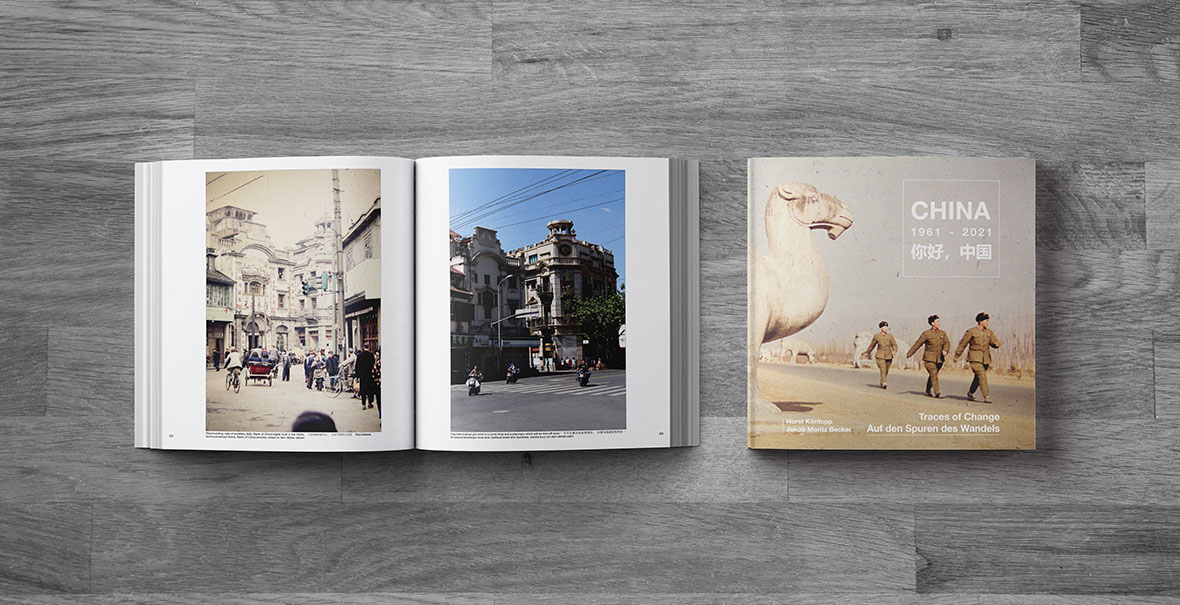

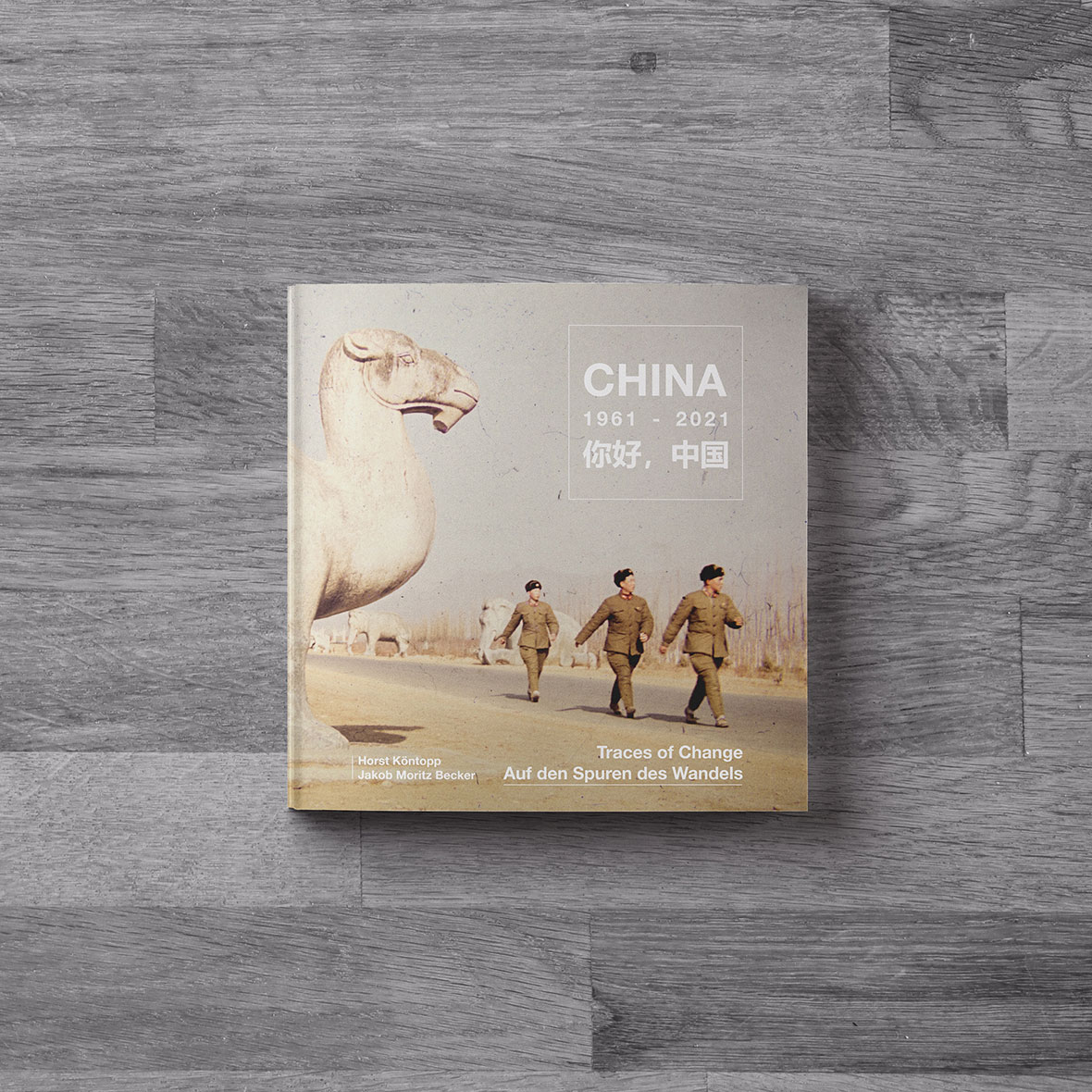

The photographs were all in color slide film and showed city and country life scenes in different provinces of China. Featuring landscape, architecture, fashion, and a fascinating human presence, they provide a rare glimpse into what life was like across the country in the early 1960s. Not just that: Köntopp’s slide photographs turned out to be the oldest sizable collection of color photographs of China known to date. Becker’s fascination with his discovery was such that, in early 2021, he published Traces of Change, a photo book with almost the entire original collection alongside photographs taken by himself on many trips to China more than half a century later as he traced his great-grandfather’s steps.

Becker’s first trip to China had nothing to do with his great-grandfather or the book. It happened before the discovery at his grandmother’s house. Trained as a civil engineer, he used to sing in the choir of the Berlin State Opera in his spare time and went to China for the first time in 2015 to attend choir festivals hosted in the cities of Shanghai and Nanjing. “The atmosphere in China back then was relaxed, everything was open, and everybody was very welcoming,” he recalls. “People from all over the world went to these festivals. It was like a big global classroom, with different groups enjoying and celebrating the beauty of art. It was a magical atmosphere.”

China left a positive impression on Becker. Back in Berlin, he began learning Chinese, already planning to return. Therefore, when he watched the photographic slides with his grandmother, they had gained a more personal value, beyond their historical importance.

The first thing he noticed was their excellent condition and photographic quality. Since they were kept in small slide frames, protected with glass on both sides, most pictures were practically undamaged, with no scratches or specks. Also, Köntopp went to China equipped with the best there was in photographic gear at the time, an Exakta Varex IIa 35mm camera and several Carl Zeiss Jena lenses, which contributed to the excellent results. “My impression of these photos is that they have a certain old charm, very different from photos today. It’s something that comes out naturally with these old lenses and colors,” Becker says.

Born in 1920, Köntopp lived through very tumultuous times in Germany. As a young adult, he served in the Second World War, in the Army Medical Service, and was imprisoned after it ended. He then returned home to what later became East Berlin and continued his medical studies to be a doctor. Köntopp was also a photo enthusiast. He shot in black and white and in color, developing the film at home in his own dark room. He even photographed for a few health periodicals as a freelance photographer. As a doctor, Köntopp helped rebuild the medical system that had collapsed during the war. His specialization was in vaccinations and social hygiene.

In 1961, along with two other doctors, Köntopp was invited on an exchange trip to China to meet Chinese doctors, visit hospitals, and observe local hygiene habits. “He didn’t take many pictures of his workplaces, but you can notice that some photos have a connection because whenever he saw something that had to do with hygiene in the street, he would take a picture. This is the only relationship I can see between his pictures and what he was doing there,” Becker says.

Köntopp’s trip happened in January and February, only months before the Berlin Wall went up. Even though East Germans still enjoyed relative freedom to travel abroad, including to Western European countries, they would more commonly travel to other countries in the Eastern Bloc of Europe. Their currency wasn’t strong nor convertible, making it very difficult to travel elsewhere—a trip somewhere as far as China was a farfetched idea, something extraordinary. The journey wasn’t easy. Köntopp and the two other doctors went by train to Moscow, where they took a plane to Tianjin with a stopover in Mongolia.

The group landed in China during the period of the Great Leap Forward, an economic plan with the goal of accelerating the transformation of the country from an agrarian society into an industrial powerhouse. However, the program had inverse and tragic effects, damaging and shrinking the Chinese economy. The worst happened in the countryside, where a combination of human errors, misleading crop reports, and natural catastrophes caused an unprecedented famine that killed tens of millions of people, the Great Chinese Famine.

Although none of this is self-evident in Köntopp photos, a closer look reveals hints of the bigger picture. “We have to distinguish between the cities and the rural landscape. If you see photos of the cities, you don’t feel a great famine is going on. The cities still received food from the countryside,” Becker says, explaining that, as history shows, rural communes reported faux harvest numbers, painting a positive picture, not to lose the favor of government administrators. Based on these misleading reports, large parts of their stock were sent to cities on a redistribution scheme. After that, when the rural communes reported truthfully that they could no longer provide high amounts, they were accused of hiding stock, which often led to food being taken forcefully. That meant that little, sometimes nothing, would be left for the rural population to eat.

“In one picture taken in the country, we see a group of children working in the field without the presence of any adults. They, too, had to ensure the harvest was properly done,” Becker says. “Knowing this context, it’s interesting to see these photos where these three German scientists are sitting in a hotel having a rich dinner with all kinds of food. It was not something common at this time,” he adds, highlighting the contrast between the harsh conditions in the countryside and city life.

Still, as Becker remarks, even in the cities, there were obvious hints of shortages. For instance, in one picture, we can see dozens of people queueing in front of a shop selling coal, which shows that even basic materials and goods weren’t available in abundance.

Even though the circumstances were harsh, Köntopp’s impressions of people in China were positive. Becker learned from his grandmother that he found Chinese people friendly, calm, and remarkably honest. “My great-grandfather always said that once he had forgotten a tie on a train in China, and he was sure that if he were to go back there, he would still find the tie in the same seat he was because no one would have taken it,” Becker laughs. Köntopp’s trust in Chinese people went as far as his field of expertise, medicine. During the trip, Köntopp felt intense tooth pain, but he didn’t know any dentists in China. His solution was to try Chinese acupuncture, which was still very unorthodox, to say the least, for the Western mentality then.

Indeed, Köntopp’s respect for the Chinese people comes across in the portraits he took. He photographed people of all ages candidly. In one particular shot, he captured a group of young boys, probably around seven or eight years old, gathered around an improvised ping-pong table. They seemed to have made the table to fit their small stature. Also, they ingeniously improvised the net out of a combination of lined bricks. In another shot, Köntopp portrays a group of little girls, about the same age as the boys, playing a game of jump rope. They seemed to have noticed him taking the photo because some of them threw intrigued gazes at the camera and opened smiles.

“I find these portraits remarkable. Today, we’re always hesitant to take photos of people, especially in a different country, but I think my great-grandfather was not afraid. The atmosphere must have been different back then because not everybody was running around with a camera. This was something new, a sort of a privilege,” Becker says.

One thing that catches the eye in particular in Köntopp’s photos is the clothes people wear. We see no traces of European fashion or even more stylish Chinese pieces such as the qipao, and not yet an abundance of Mao suits that became popular in the following years. Instead, there’s a predominance of modest and untailored tang style jackets, baggy pants, and cloth slip-on shoes, all worn by men and women, even in the biggest cities.

Beyond fashion, the mood in Köntopp’s photos seemed modest and, paradoxically, more idyllic. As Becker notices, even when the architecture was preserved, the aura of most places has changed drastically from those times. “Architecture-wise, some of these places he visited look much like they do today. But they feel completely different because they are so crowded today,” he says, showing a photo of the Long Corridor at the Summer Palace in Beijing taken by his great-grandfather. The corridor is uncrowded, with only a few people strolling. But then Becker compares this shot with a recent photo he took of the same corridor overcrowded with people in guided group tours. “This is what fascinated me. My great-grandfather’s photos show the China we all imagine, a peaceful, harmonious, and spiritual place,” he says.

As he studied the photos, Becker wondered if he could find some of the less obvious places his great-grandfather had photographed. Since Köntopp didn’t leave a proper travel journal behind, Becker would have to rely on the images themselves and clues his great-grandfather left in them for guidance. Köntopp had scribbled notes and succinct descriptions in many of the pictures; sometimes, these scribbles revealed the name of the city or area where he shot them; sometimes, they were vague, just simple keywords, like “in the hotel,” for instance. Besides, not all of them were legible, especially considering how intricate handwriting was in the past. And there was yet another complicating factor: Köntopp had used the now obsolete German names given to those places.

To Becker, decoding these clues was a discovery process in itself. His investigation of his great-grandfather’s journey began in Germany. He researched online, on Google and Baidu, and, to his surprise, he found many of the places he was looking for with a simple research. When the difficulty level increased, he asked friends and people he knew in China for help. In the following years, Becker visited China for various reasons. He took the chance to stir his travels within the country towards the places his great-grandfather had been sixty years before.

Still, finding cities and locations didn’t mean the job was done. Becker needed to find the exact spots Köntopp stood to photograph. Some were easy. “Memorials, parks, and gardens didn’t change much. Like the Summer Palace; it didn’t change at all. Maybe the colors became a bit more bright and catchy, but the structure and architecture remain the same,” Becker says.

Some spots, however, were much harder to locate. “Hutongs and other places where people lived in old houses have changed a lot. These were often in the city centers. If you look at the city center of Beijing, it’s full of new modern buildings now. A lot of this old architecture was seen as outdated and replaced,” Becker says.

To locate some places that had changed radically, and some that were simply too hidden, Becker used an interesting approach: he tapped into the memory of the elderly. “I would show pictures to the elderly in the streets and ask them if they knew these places. They really remembered places and promptly started giving me directions. I would follow them, and sometimes, suddenly, I would find the exact location I was looking for,” he says.

Other times, Becker would find nothing of what he was looking for, even if he were in the right place. Some landscapes had changed almost entirely, and he had to look for clues in the photographs that he could identify, like a stream of water or a small bridge, to ensure he was in the right place. Wherever he went, he would try to capture the same angle his great-grandfather did. That wasn’t easy either: sometimes new additions to the landscape had obstructed the view or made it impossible for him to stand in the same place Köntopp did in the past.

Unsurprisingly, some places proved impossible to find. Some spots had changed entirely. Whatever was visible in Köntopp’s photos had utterly vanished to open space for large modern buildings or massive infrastructure projects. “I could only find the places that have changed to a certain degree. But many places changed so much that I had no way of recognizing them. I will never be able to find them—probably nobody will.”

Contrastingly, some things remain the same. A few times, Becker found places where even the lifestyle seemed untouched by time. “With the car, I had more flexibility to go wherever I wanted, so I drove to some remote areas in Sichuan where you can still find life intact and original,” he says. However, he realizes it’s a matter of time until things change. Even in such places, there are hints of modernization, and they usually appear with tourism. “Sadly, most people will sacrifice tradition and culture for the money that comes with mass tourism.”

Becker noticed that in cities, some of the old buildings had their facades stripped of the original ornaments that decorated them, like Chinese texts, dragon images, and friezes. These buildings gained a more practical and unaffected appearance. The most noticeable change, however, was in street life. The book has pictures of 1961 showing people playing games on the sidewalk, reading, hanging their clothes to dry in public, and practicing qigong in the streets and parks. Scenes that you can still see in today’s China but that are getting increasingly rare due to the changes in lifestyle and the results of the gentrification of traditional neighborhoods.

“In the pictures of 1961, the streets were alive, full of people. If you analyze them, you have the impression of a functional social system,” he says, showing a photo of a lively street with many people coming and going on foot, bicycles, and rickshaws. A young man is pulling a cart filled with sacks in the back, and there’s an overall sense of how social the street was back then.

In the book, Becker juxtaposed this picture with a recent shot of the same street. We can immediately notice the emptiness: only a few scooters are racing by, and now there’s a pedestrian crossing, a Family Mart shop, and a pharmacy. The ornaments in one of the buildings are gone, and another building disappeared completely, possibly to open space for a wider road. “It’s a matter of perspective,” Becker says. “If you could ask the people back then, they would probably love what it looks like today: clean, functional, and people having enough money to buy things and eat. At the same time, in our position today, we look back at them and feel this dreaminess of the good old times. We can see the history that has been removed, and now it’s gone.”

Traces of Change is organized into two parts and subdivided into many chapters. The first part shows only Köntopp’s photographs; the second is the re-photography part, where Becker combines the past and the present. Each chapter corresponds to a stop in Köntopp’s journey. Inspired by the poetic character of the photos, Becker opens them with a traditional Chinese poem connected to the local atmosphere.

Even though the textual elements only appear minimally in the book as an introduction to Köntopp’s trip, captions, and the poems mentioned above, Becker had to invest time in researching background information and translating the text, including the poems, to English, German, and Chinese. It was something he wouldn’t be able to do without the help of his father, his girlfriend, and other collaborators. The processes were fairly complex, mainly because of the number of photographs he included in the book, almost the entire colored collection, except for a few duplicates.

Köntopp’s entire photo collection, however, was even more extensive. Becker’s grandmother told him there was also a series of black and white photographs he took in China with another camera, but they had disappeared with time. Had they been around, they would likely make it to this book, or perhaps another one. Becker is eager to protect and share every visual material he can with the broader public. “I wanted to leave nothing out,” he says. “Even though some of these pictures might not look special, they might be relevant to some people. They will see details that you and I won’t. Altogether, these pictures help construct an understanding of the time” he says.

Köntopp’s pictures of China provide precisely this. They are rare missing pieces that help us assemble a better understanding of Chinese society at the beginning of a pivotal period for the country. But they do so in a unique way, distinguishable from the usual scenes of despair or ideological fierceness that dominate the imagery available from the time. They’re more humane and perhaps even more meaningful, taken by an amicable traveler who was genuinely curious about the country in a seemingly apolitical manner. Together with Becker’s recent photographs, they form a window not just to reinterpret how Chinese people lived in the past but where they (and we) stand today.

Like this story? Follow Neocha on Facebook and Instagram.

Website: www.tracesofchange.de

Instagram: @tracesofchange

Contributor: Tomas Pinheiro

Chinese Translation: Yang Young