Between planet and Party, China’s decarbonized future is hazier than ever

As Europe burns and China swelters through a merciless summer, the Paris climate goals are a distant mirage. Determined to double China’s GDP by 2035 and overtake the U.S., it seems impossible that Xi Jinping can meet both his political and environmental commitments.

In its most dire assessment yet, in April the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) told us that “it’s now or never.” Only “rapid, deep and immediate” cuts in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions can prevent runaway global warming and the collapse of civilization.

To keep global warming below 1.5°C, no more than 500 billion tons of CO2 can be emitted beyond 2020, equivalent to little more than a decade of global emissions at current rates. Achieving the 1.5°C Paris goal means that coal use must decline by 95% by 2050, oil by 60%, and gas by 45%. The decreases required to limit warming to 2°C are not much different. Under all scenarios, no more fossil-fuel power plants can be built and most existing ones must be decommissioned.

The IPCC message is clear: “Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action will miss a brief window of opportunity to secure a livable planet and sustainable future for all.”

Prioritizing economic growth over emissions suppression

Most leading industrial nations have reduced their emissions to some degree. U.S. emissions in 2020 were down 14% from their peak in 2005; EU emissions were down 32% from their peak in 1981; Japan’s have dropped 14% from their peak in 2013. Yet these declines are still insufficient to meet Paris obligations that, in themselves, are already insufficient to keep the rise below 1.5°C, or even 2.0°C, degrees. By contrast, China’s emissions increased relentlessly, more than quadrupling from 1990 to 2020. China now emits more than twice as much as the United States, with a GDP just two-thirds as large. In the first half of 2021, rebounding from the first wave of COVID, China’s CO2 emissions rose past pre-pandemic levels with an all-time-high 20% increase in the second quarter before dropping back during the first half of 2022 as the real-estate sector collapsed. Omicron lockdowns, and drought-induced hydropower reductions, have reduced economic growth to near zero. With the loss of hydropower, Beijing has little choice but to go back to coal for reliable electricity generation.

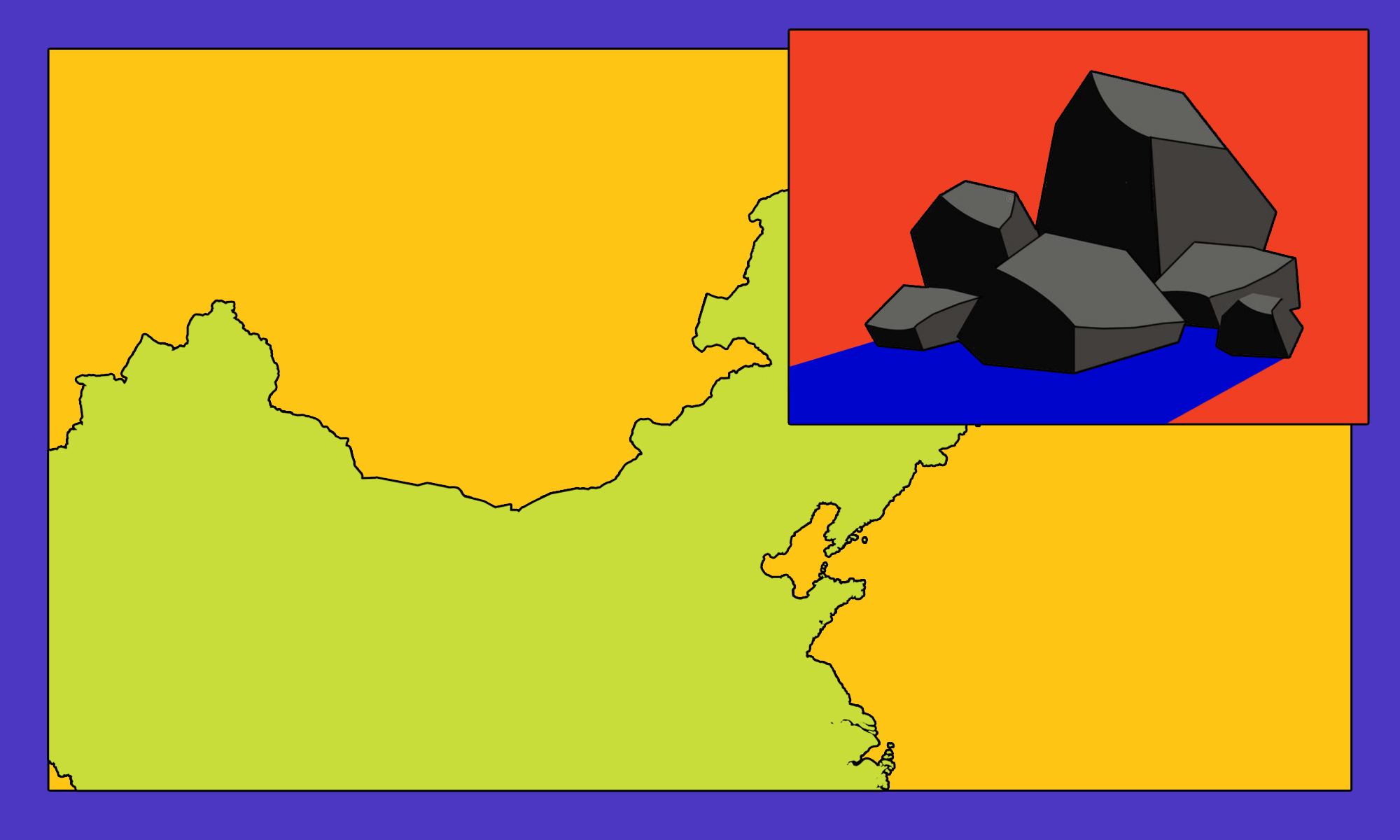

Since 2016, Beijing has repeatedly promised to phase out coal and coal-fired power production, and repeatedly reneged on those commitments. While coal-fired power plants are being decommissioned around the world, a new mega-mine in Ordos will produce 15 million tons each year and could do so for almost a century.

In March, the National Development and Reform Commission committed to boosting domestic production by 300 million tons. China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of coal, and production hit record levels last year. Last summer’s 14th Five-Year Plan stresses the role of coal in “ensuring basic energy needs.”

China may have stopped building coal-fired power plants abroad, but it’s building more at home in a bid to ensure energy self-sufficiency — locking the country into coal reliance for many decades to come, derailing the transition to renewables, and dooming China’s prospects of meeting its Paris obligations. In 2020, the government approved 47 gigawatts of new coal power, more than three times the new capacity approved in 2019. In 2021 it approved another 73.5 gigawatts — more than five times the 13.9 gigawatts proposed in the rest of the world in that year. It approved even more earlier this year.

And it’s not only coal. Beijing is investing heavily in oil and gas and has built pipelines to Kazakhstan and Russia to import natural gas. The Siberian pipeline alone will enable China to import 1.3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas a year (two-thirds as much as Russia supplies Germany) through 2049. China is now the world’s largest importer of natural gas and oil.

Unsurprisingly, 85.2% of China’s primary energy consumption in 2020 still came from fossil fuels, down just 7% from 2009. Fossil fuels accounted for 68.2% of electricity generation in 2020 (65% from coal), down from 79.8% in 2009. Solar and wind power have grown in recent years, but they’re so starved of investment compared with fossil fuels that they contributed only 11.7% of electricity generation in 2020.

In 2020, Chinese leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 pledged to “transition to a green and low-carbon mode of development” and to “peak the country’s CO2 emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.” But how will China ever get off fossil fuels with so much investment flowing into coal, oil, and gas, and so little into solar and wind?

Fossil fuel dependence: a political issue

There is no chance that Xi will meet his carbon-neutral goal. He cannot decarbonize the economy because, since Mao’s day, the Communist Party has been committed to overtaking the United States to become the world’s leading economy. This leaves Xi little choice but to maximize growth of the very industries that are driving emissions off the charts, including coal-fired electricity generation. In my recent book China’s Engine of Environmental Collapse, I showed how Beijing relies on only three tools to drive growth: industrialization, employment policy, and consumption.

In a world dominated by more advanced and powerful capitalist nations, Mao and his successors understood that their only guarantee of security is to overtake the United States by turning China into the world’s leading superpower. The Soviet Union’s failure to win economic and arms races with the U.S. doomed the Soviet Communist Party, a fate Xi is determined to avoid.

Capitalist employers have no obligation to ex-employees. If workers are laid off, it’s not the capitalists’ problem. It’s not even the government’s problem — except in severe downturns like the Great Depression when there is threat of unrest or even revolt.

But the CCP was once a real workers’ party, and because it derives its legitimacy from its status as the self-appointed representative of the working class, it can’t completely ignore the workers. In November 2013, Premier Lǐ Kèqiáng 李克强 made the position clear: “Employment is the biggest thing for well-being. The government must not slacken on this for one moment… For us, stable growth is mainly for the sake of maintaining employment.”

Keeping hundreds of millions of workers occupied often means producing superfluous steel and building needless infrastructure. Maximizing employment is a major driver of overproduction and over-construction, so-called “blind growth” and “blind investment,” and profligate waste across the economy.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

The Soviet Communist Party collapsed in 1991, only two years after the CCP’s own near-death experience in Tiananmen Square. The Party leadership then resolved to create a mass consumer economy and raise incomes to focus attention on shopping and accumulating wealth, taking the masses’ minds off politics.

Since the early 1990s, successive Five-Year Plans have prioritized new consumer industries, and the government has promoted one consumer craze after another: bike sharing, cars, condos, cruise ships, food deliveries, golf courses, online shopping, shopping malls, theme parks, tourism, video games, and more.

After centuries of poverty and decades of privation, the Chinese were surely overdue for some creature comforts. But mindless consumerism for the sake of consumerism has contributed mightily to China’s, and the world’s, waste and pollution crises. Less enviable among the country’s many firsts is this headline, from China Daily in February 2015: “China No. 1 dumper of plastic into ocean.”

To maximize economic growth, employment, and consumerism, Beijing has no choice but to let polluters pollute: There’s just no way around it. This tendency is further exacerbated in China’s case because, as nationalists concerned with self-reliance, the Party strives to rely on domestic energy resources. And that means coal.

Decarbonizing industry: a technical issue

There are, I believe, insurmountable barriers to decarbonizing China. The country is home to the world’s largest concentration of carbon-intensive, hard-to-abate industries — aluminum, aviation, cement, chemicals, shipbuilding, steel.

Thermal electricity generation (90% coal, 10% gas) accounts for around a third of emissions. Replacing coal-fired power plants with solar or wind generators might reduce emissions by as much as a third — a huge gain, if it can be done.

But half of China’s greenhouse emissions come from hard-to-abate industries. Most cannot be decarbonized with current or anticipated technology, certainly not in time to avert runaway global heating and climate collapse. Decarbonizing those industries has defied efforts to date.

While scientists and engineers are dreaming up new technologies — carbon capture and storage, electric and hydrogen airplanes, hydrogen steel, etc. — commercializing those at the scale necessary to replace fossil fuels may never happen. Even when possible, it will take many decades to transform the world economy. For example, Bloomberg’s New Energy Frontier estimates that even with a crash program, the global steel industry could not adopt hydrogen for more than 50% of output before 2050. McKinsey estimates that with massive funding, hydrogen could meet 14% of America’s energy needs by 2050. Too little, too late.

Worse yet, 96% of the world’s commercially available hydrogen is derived from fossil fuels. Producing “green” hydrogen would require a monumental effort to create a huge and entirely new “electrolyzer” industry based on technologies that are still in their infancy and unproven at scale. Even if such an industry could be built in time, the daunting hazards of transporting, storing, and safely fueling steel mills and vehicles, let alone airliners with hydrogen, have no ready solution. Aluminum, aviation, cement, chemicals, and all the other hard-to-abate industries face similar constraints.

A recipe for disaster

Given that we don’t have more decades to waste, the only way to effect “immediate and deep” cuts is to cut production across the economy, from fossil fuels to all manner of superfluous, wasteful, and polluting industries, from ghost cities and aircraft carriers to disposable plastic junk to iPhones 7, 8, 10, 13, etc..

We don’t need self-driving cars, flying robo-taxis, overnight delivery services or dashboard displays the size of TV sets. And it’s not just China and the Chinese Dream: the same arguments apply to Western capitalist economies. A voice-controlled microwave is no more necessary in Baltimore than it is in Zhengzhou.

Yet suppressing production is the one option Xi Jinping cannot accept because those industries have been indispensable to China’s rise and underpin the dream of “the great rejuvenation of the nation” and overtaking the West to the ever-lasting glory of the Communist Party.

Xi can “transition to a green and low-carbon mode of development,” or he can pursue his dream of superpower industrial supremacy. He can’t do both. China’s “engine” of economic growth is driven above all by the superpower ambitions of the CCP. Western capitalist economies are driven by the profit motive. East and West, the fetish of perpetual growth is the engine of planetary environmental collapse. Either we and the Chinese reverse course, or we proceed to our mutual doom.