Tattoos as female power: Wearing female experiences on the skin

Pink elephants, fish, genitalia: For young feminists in China, tattoos have become a way to express their womanhood and take back their bodies.

In China, tattoos have long been associated with thugs and “bad girls.” But today, that is changing — and one tattoo artist in particular is helping women express themselves in ink.

When Língméng 灵濛, a Chongqing-born millennial also known by her nickname “kk,” began tattooing in 2018, she said she felt that the culture was very male-dominated. Determined to change that, she founded 11km daily studio in Chengdu one year later, leaving an advertisement job and a work environment that she called “a bit misogynistic.”

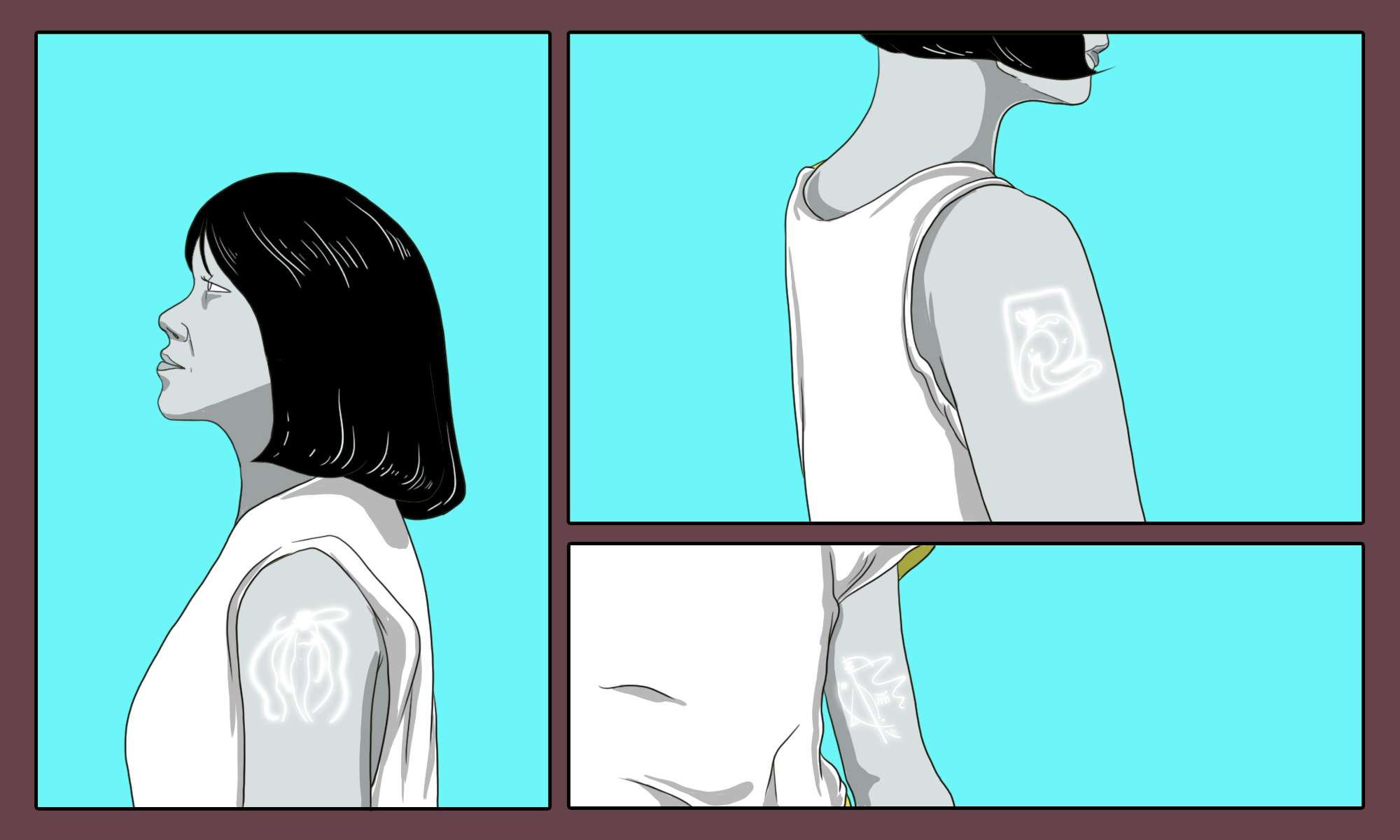

Her first gender-themed project, F.EVER: Find Female’s Feelings Forever, was launched in April 2020. She solicited stories online from women about their growth and experiences. These stories were visualized as tattoos, which the participants had the option to have inked.

The project has received more than 100 submissions. Chinese women shared their thoughts on empowerment, intimate relationships, female identity, fertility issues, and gender violence. Within a year, more than 30 participants had gotten tattoos based on their submissions.

For Lingmeng, these stories were not just inspiration for her tattoo designs, but another way to promote women voices and raise gender awareness in China: “I also wanted to build a platform for girls to tell their own stories, hoping that more people can pay attention to the individual life experiences of women.”

The submissions, paired with Lingmeng’s art, were eventually exhibited at a series of art shows in Chengdu, including Us Here Now at Chengdu Women’s Month in March 2021. Lingmeng’s own tattoo studio also showcased a mini exhibition, The Girl is Magic Art, featuring candles in the shape of the female body.

“For women,” Lingmeng said, “we want to provide them with a space where they can feel comfortable, safe, relaxed, and not disturbed during the tattoo process; at the same time, we also want to break the stereotypes of tattoo parlors.”

In China, getting inked has traditionally been seen as a contentious act. Filial piety in Confucianism holds that “the skin of your body is received from your parents” (身体发肤,受之父母 shēntǐ fà fū, shòu zhī fùmǔ), and tattoos are frowned upon by elder generations. Women with tattoos are often sexualized or stigmatized as “bad girls.” There is an increasingly evident crackdown on tattoo culture, including requirements for tattooed taxi drivers in Gansu to remove their body ink and bans on tattoos in soccer.

On the other hand, tattoos are increasingly popular among younger generations, who embrace them as a new art form and reject the stigma. Women, especially, are using tattoos as a way of speaking out.

Xiāo Měilì 肖美丽, a well-known Chinese feminist activist, asked Lingmeng to design a tattoo for her in May 2021, after experiencing cyber attacks as the result of one of her social media posts. In the post, she shared a video of a man throwing hotpot oil at her after she asked him to stop smoking; the post eventually resulted in the removal of her Weibo account.

Xiao described the tattoo as a ray of light, and wrote: “I hope I live in an era where…I don’t go against my principles because of fear or because I’m being besieged. I feel that the effort to choose the right thing is the ‘light.’ There are many areas where you can give up, give in, or compromise, but you must never be a part of the darkness. I want to use this tattoo to remind myself to stick to my principles, and to do the next right and virtuous thing even when times are tough.”

Pān Jìng 潘婧, a 28-year-old who works at a Beijing-based internet company, tattooed a uterus on the inner side of her upper arm when her mother was about to have her uterus removed due to an ovarian cyst. She told me, “First, even if women don’t want to have children, I think the uterus is a particularly important organ for women. Second, for myself, my mom’s womb was my first little house in my life. I hope to leave memories of her on my own body, so that I will always remember that I grew up there.”

Pan added that her boyfriend accompanied her when she got the tattoo, but he didn’t seem to understand why she did it. “I think men still don’t quite understand women’s emotional needs. My male friends around me, including my boyfriend, always think it is bad for girls to get weird tattoos, but my girlfriends seldom raise objections.”

Lǐ Zhuóyǐng 李卓颖, 25, a recent graduate in Shanghai, chose to get a cyborg tattoo, designed in proportion with her body, to represent her feminist identity. When writing her undergraduate dissertation, she read Simians, Cyborgs and Women by Donna Haraway, and was inspired by its interpretations of feminism. “If women were to want a world of complete gender equality, it would have to be a world where women were no longer burdened by childbirth,” she said. “One way ahead for women would be to become cyborgs. This became the inspiration for my tattoo.”

Other tattoos designed by Lingmeng as part of the F.EVER project include a clitoris in the shape of a flower, described by the person who submitted it (@水母啫喱) as “an organ that allows us to take control of our own sexual pleasure” and “liberation from the traditional idea that a woman’s role in a sexual relationship is only to ‘serve’ the male.” A pink elephant, for @lcarus, was “a metaphor that…the more you are afraid of [gender violence], the more you have to face it,” specifically mentioning the Nth room case. @iris-yu, meanwhile, submitted (and got inked) a fish tattoo, which she described as “contradictory and complex…tough and tender.”

Lingmeng has continued to explore ways to disrupt stereotypes in the tattoo industry. She hopes to normalize tattoo art among women, and thinks that the stigma and bias around tattoos comes from male domination of the industry. One solution is to place tattoos in more public settings, such as in photos, illustrations, and exhibitions, to raise awareness.

“I hope to make [tattooing] more of an everyday thing,” Lingmeng said. “So it is imperative to raise voices, and it needs to be…more visible to the public.”

In May, Lingmeng temporarily closed her tattoo studio because of personal health reasons. Returning to Chongqing, she joined a painting program with a group of high school art students. Even though the majority of the art students were women, Lingmeng felt that very few displayed gender awareness, and among those who had tattoos, they were mostly small and hidden.

This autumn, Lingmeng plans to start a new project, Girl’s Bedroom Tattoos (女孩的卧室文身 nǚhái de wòshì wénshēn), relocating the tattoo work to her female customers’ own bedrooms, then producing a collection of photographs with the stories behind the designs. “If the location is changed to their familiar environment,” she explained, “I wonder if there will be some new experience.”

As more women seek to make their experiences heard, tattoos have become a method of telling stories. It may be a small amount of ink, but it represents a permanent mark on bodies that women control. “Feminism has given me my own freedom and power,” Lingmeng said. “[With the] constant compression of space for women’s voices…no matter what the state of the overall environment we are in, someone needs to speak out, innovate, and renew.”