Breaking ground and making waves: Eight noteworthy women in Chinese cinema

The history of Chinese cinema is filled with creative, courageous women who evolved the industry with their unique talents and perspectives. We’ve rounded up eight Chinese women who have made significant advances in directing, producing, writing, or acting.

This article is brought to you by Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, a leading international joint venture university based in Suzhou, Jiangsu, China.

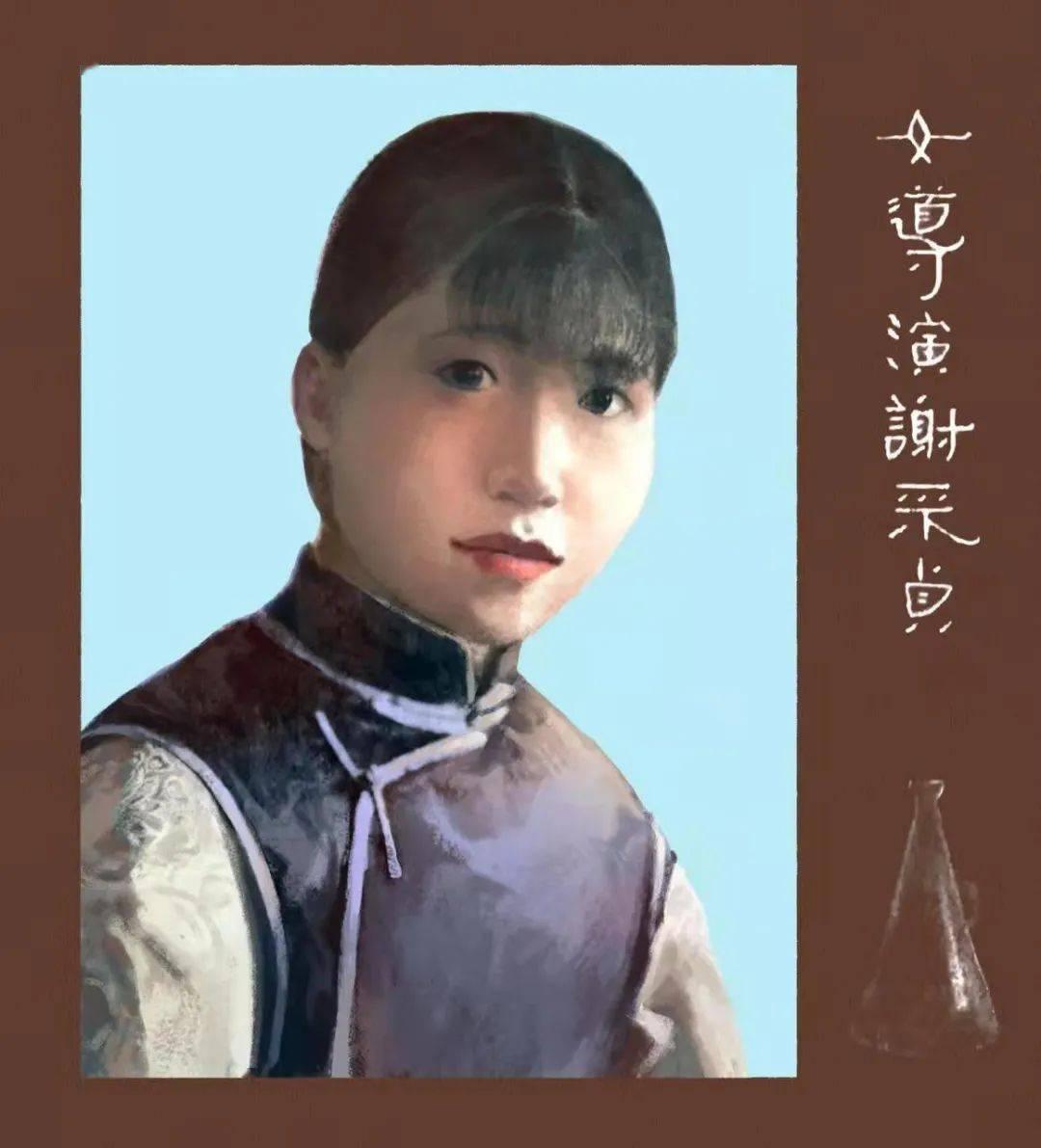

Have you heard of a woman called Xiè Cǎizhēn 谢采贞? Unless you are a scholar of Chinese film history, then chances are you haven’t. Active in the 1920s, Xie originally started as an actress and went on to become the first woman in China to helm a film. Sadly, her directorial work was lost for a long time and her name hardly rings any bells these days.

But make no mistake, Xie was a pioneer. It is women like her who influenced Chinese cinema in a profound way, challenged the industry’s male-centric status quo, and inspired generations of Chinese women to be strong forces both behind the camera and on the big screen.

Below, we take a look at eight women whose contributions to Chinese cinema deserve to be recognized and celebrated.

Xie Caizhen is considered to be the first woman in China to direct a film. She got her start in the big-screen business as an actress, landing key roles in films like Some Girl, Filial Girl Takes Revenge, and He’s Not a Fool — all of which came out in the 1920s. As her acting career flourished, Xie was tapped by Nanxing Film Company in 1925 to direct and play a leading role in the silent feature film An Orphan’s Cry.

As the only known directorial work by Xie, An Orphan’s Cry is a family melodrama that also offers a glimpse into the life of working-class women at the time. Upon the film’s release, it is said to have created ripples among audiences owing to Xie being a woman and the film’s complex storyline. Local newspapers reported that the film stayed in theaters for eight days due to high demand (the average run of a film in theaters was three or four days at the time) and had a rather impressive box-office record.

But “for people who didn’t spend years at film school, they rarely know her name,” says Dr. Xiao Lu, an assistant professor in the School of Cultural Technology at XJTLU Entrepreneur College (Taicang). “I wish there were more digital or physical materials that could be easily accessed via a library or the internet,” Lu says. “I would love to learn more about her and her work.” But Lu notes that the loss of work in early Chinese cinema is a “common problem,” and it happens to women filmmakers disproportionately both in China and overseas.

Esther Eng was the true definition of a trailblazer and a go-getter. Born in San Francisco in 1914, Eng grew up with a passion for films. As a teenager, she learned about them by watching hundreds in local theaters. At the tender age of 19, Eng convinced her father to create a film production company and name her as the co-producer of the 1936 movie Heartaches, a Chinese-language romantic drama set in the context of contemporary Sino-Japanese conflicts.

Eng’s first directing credit was for National Heroine, which was filmed during her time in Hong Kong. Upon its release in 1937, the movie received much praise from local audiences, who were captivated by its portrayal of a heroine fighting alongside male comrades for the sake of China. This film’s success prolonged Eng’s stay in the Asian city for two more years, during which she continued to direct more films, including It’s a Women’s World, a feminist movie featuring an all-female cast of 36 actresses. After she returned to the Bay Area in 1939, Eng shifted her focus from filmmaking to distributing Cantonese films in Central and South America.

Throughout her legendary career, Eng was always upfront about being a lesbian. Unbothered by other people’s opinions, Eng often dressed herself in men’s clothes and openly talked about her same-sex relationships.

Eng was largely forgotten until a 1995 column in Variety drew attention to her. In the column, Todd McCarthy, who was the magazine’s chief film critic at the time, described Eng as “an Asian woman filmmaker who had utterly eluded the radar of the most diligent feminist historians and sinophiles.” Golden Gate Girls, a 2013 documentary by filmmaker S. Louisa Wei, also helped restore Eng’s place in film history.

Before entering the film business, Pu Shunqing was a famed playwright whose work celebrated women embracing feminism and subverting gender stereotypes. After marrying Hóu Yào 侯曜, a pioneering Chinese film director, screenwriter, and film theorist, Pu got involved in filmmaking by starring in Hou’s The World Against Her, a movie about the troubled life of a young mistress.

Pu then adapted her own play Cupid’s Puppets into a film of the same name, a melodrama about a female journalist that made Pu China’s first female scriptwriter. According to Columbia University’s Women Film Pioneers Project, Cupid’s Puppets is noted as “the first Chinese film narrated from a female perspective.” Pu also heavily influenced Hou’s work, convincing him to become an advocate of women’s rights during their years of collaboration.

Never content to just be the daughter of the renowned 1940s director Huáng Zuǒlín 黄佐霖 and actress Jīn Yùnzhī 金韵之, Huang Shuqin was one of China’s most prestigious female directors, who carved out her own place in the film industry, especially among the fourth generation of filmmakers in the country, by introducing a unique, female point of view into her work.

Coming from a background of formal education and classic training, Huang graduated from Beijing Film Academy in 1964. However, she was unable to make films until 1981 because of the Cultural Revolution. Since her directorial debut, The Modern People, released in 1981, Huang helmed a total of 10 movies and five TV series. The most notable of these is Woman Demon Human, a powerfully unorthodox drama that’s regarded by critics and scholars as the first truly feminist film made in China.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Part biopic and part psychological mystery, Woman Demon Human follows the life of a female Beijing opera star named Péi Yànlíng 裴艳玲, who was recognized for portraying male roles onstage, and who stars in the film, playing a fictional version of herself, Qiū Yún 秋芸. With the opera as its backdrop, the film gives elliptical fragments of Qiu’s career, from enduring brutal training regimens and experiencing incipient fame to suffering losses and tackling the trappings of gender conventions both in her field and in society at large.

Sijia Meng, a part-time lecturer in the School of Cultural Technology, XJTLU Entrepreneur College (Taicang), who is currently completing a doctorate on contemporary Chinese society through cinema at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) in Suzhou, notes that before Huang, Chinese women directors were “more concerned with bigger issues such as revolutionary problems in their work, just like their male counterparts.” In an age where “female voices and perspectives were missing” in Chinese cinema, Huang differentiated herself with her sensitive female point of view on women’s topics and her empathetic portrayal of the plight of women.

Heading into the Chinese New Year holiday in 2021, few imagined that Hi, Mom — a feature from a first-time director with a relatively unknown cast — would bring in big bucks during one of the most competitive periods at the Chinese box office. But the hilarious tearjerker, which sees its director, Jia Ling, playing a woman who travels back in time to befriend her deceased mother, struck a special chord with audiences and shattered all expectations, raking in more than 5.41 billion yuan ($781 million) in ticket sales.

The appeal of Hi, Mom mainly lies in its relatability, Lu says. “It’s a straightforward story and it’s down to earth. It tells an accessible story,” she adds.

In addition to collecting a cinematic success under her belt, Jia, who was previously a popular xiangsheng performer and comedian, also made history with Hi, Mom as the movie surpassed Patty Jenkins’s Wonder Woman to make her the world’s highest-grossing female director for a single film.

Meng hopes that Jia’s commercial success at the box office will bolster the status of women in the Chinese filmmaking business, but she points out that opportunities for female filmmakers still don’t occur frequently enough. “Women can make great films if given the chance,” she says, adding that a cohort of up-and-coming women directors have proved themselves in recent years, including Shào Yìhuī 邵艺辉 and Yáng Lìnà 杨荔钠.

A member of China’s star-studded fifth generation of film directors along with Chén Kǎigē 陈凯歌 and Zhāng Yìmóu 张艺谋, Li Shaohong stands out from her peers by telling realistic tales of rural life in China that reflect the transformation of society as well as people’s ideology during tumultuous times.

Blush, a 1995 film telling the story of the Chinese government’s campaign to “reeducate” prostitutes through the eyes of two women and a female narrator, is Meng’s favorite work from Li. “Compared with her male counterparts, Li’s female perspective makes the movie a sharp, unconventional, and more delicate portrayal of the female subject, specifically underclass, marginal women like prostitutes,” Meng says. “Li’s work also presents women’s individuality, the diverse qualities among women.”

Beyond being a prolific, award-winning director, Li has also shattered multiple glass ceilings in the Chinese film industry by having her own production company and being the first female head of China Film Director’s Guild.

A prolific actress and a rare example of a Chinese celebrity being recognized globally, Gong Li established herself as one of the biggest international stars to come out of China in the early 1990s, starring in Oscar-nominated films like Ju Dou, Raise the Red Lantern, and Farewell My Concubine. She then cemented her status as a global actress with films like Memoirs of a Geisha and Mulan.

Acclaimed Chinese film director Zhang Yimou, who is internationally known for helming several Oscar-nominated films and choreographing the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics, played a crucial role in Gong’s early career by casting her as the leading actress in multiple movies. Although it was Zhang’s mentoring and guidance that helped Gong rise to prominence, Meng mentions that her favorite acting performance from Gong is from Coming Home, a 2014 historical romance movie directed by Zhang.

Meng says: “Gong’s acting has matured in this film compared with her early films with Zhang. She has become more mature, establishing her own critical thinking on the role she is assigned to play, instead of just passively following the script, so she offered constructive suggestions on the development of the script to Zhang and they were later adopted by the director.”

Having studied at the London Film School in the early 1970s and worked as the assistant director to martial arts film master King Hu (胡金铨 Hú Jīnquán) afterward, Ann Hui was showered with accolades for her debut feature, The Secret, when it was released in 1979. Since then, she has directed 26 features, including Boat People, A Simple Life, and The Golden Era, which are among the six films that won her best director titles at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

In 2020, the veteran filmmaker became the first woman director to win the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement from the Venice Film Festival. In his speech honoring Hui, Venice chief Alberto Barbera described her as one of “Asia’s most respected, prolific, and versatile directors of our times,” someone who never abandoned an auteurist approach while still paying attention to the commercial side of movies.

“In her movies, she has always shown particular interest in compassionate and social vicissitudes, recounting — with sensitivity and the sophistication of an intellectual — individual stories that interweave with important social themes such as those of refugees, the marginalized, and the elderly,” Barbera remarked. “In a trailblazing fashion, through her language and her unique visual style, not only has she captured the specific aspects of the city and the imagination of Hong Kong, she has also transposed and translated them into a universal perspective.”

Jiayun (Jenny) Feng is the Society and Culture Editor at The China Project. Born and raised in Shanghai, she is a bilingual journalist committed to reporting on China-related issues with a global perspective. Read more

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Performance cookies are key in allowing web site screens and content to load quickly on all types of devices.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| _gat | This cookies is installed by Google Universal Analytics to throttle the request rate to limit the colllection of data on high traffic sites. |

| YSC | This cookies is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos. |

Preference cookies are used to store user preferences to provide them with content that is customized accordingly. These cookies also allow for the viewing of embedded content, such as videos.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| bcookie | This cookie is set by linkedIn. The purpose of the cookie is to enable LinkedIn functionalities on the page. |

| lang | This cookie is used to store the language preferences of a user to serve up content in that stored language the next time user visit the website. |

| lidc | This cookie is set by LinkedIn and used for routing. |

| PugT | This cookie is set by pubmatic.com. The purpose of the cookie is to check when the cookies were last updated on the browser in order to limit the number of calls to the server-side cookie store. |

Analytics cookies help us understand how our visitors interact with the website. It helps us understand the number of visitors, where the visitors are coming from, and the pages they navigate. The cookies collect this data and report it anonymously.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| __gads | This cookie is set by Google and stored under the name dounleclick.com. This cookie is used to track how many times users see a particular advert which helps in measuring the success of the campaign and calculate the revenue generated by the campaign. These cookies can only be read from the domain that it is set on so it will not track any data while browsing through another sites. |

| _ga | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gid | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| _omappvp | The cookie is set to identify new vs returning users. The cookie is used in conjunction with _omappvs cookie to determine whether a user is new or returning. |

| _omappvs | The cookie is used to in conjunction with the _omappvp cookies. If the cookies are set, the user is a returning user. If neither of the cookies are set, the user is a new user. |

| GPS | This cookie is set by Youtube and registers a unique ID for tracking users based on their geographical location |

Advertisement cookies help us provide our visitors with the most relevant ads and marketing campaigns.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| __qca | This cookie is associated with Quantcast and is used for collecting anonymized data to analyze log data from different websites to create reports that enables the website owners and advertisers provide ads for the appropriate audience segments. |

| _fbp | This cookie is set by Facebook to deliver advertisement when they are on Facebook or a digital platform powered by Facebook advertising after visiting this website. |

| everest_g_v2 | The cookie is set under eversttech.net domain. The purpose of the cookie is to map clicks to other events on the client's website. |

| fr | The cookie is set by Facebook to show relevant advertisments to the users and measure and improve the advertisements. The cookie also tracks the behavior of the user across the web on sites that have Facebook pixel or Facebook social plugin. |

| IDE | Used by Google DoubleClick and stores information about how the user uses the website and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This is used to present users with ads that are relevant to them according to the user profile. |

| mc | This cookie is associated with Quantserve to track anonymously how a user interact with the website. |

| personalization_id | This cookie is set by twitter.com. It is used integrate the sharing features of this social media. It also stores information about how the user uses the website for tracking and targeting. |

| PUBMDCID | This cookie is set by pubmatic.com. The cookie stores an ID that is used to display ads on the users' browser. |

| TDCPM | The cookie is set by CloudFare service to store a unique ID to identify a returning users device which then is used for targeted advertising. |

| TDID | The cookie is set by CloudFare service to store a unique ID to identify a returning users device which then is used for targeted advertising. |

| test_cookie | This cookie is set by doubleclick.net. The purpose of the cookie is to determine if the users' browser supports cookies. |

| uid | This cookie is used to measure the number and behavior of the visitors to the website anonymously. The data includes the number of visits, average duration of the visit on the website, pages visited, etc. for the purpose of better understanding user preferences for targeted advertisments. |

| uuid | To optimize ad relevance by collecting visitor data from multiple websites such as what pages have been loaded. |

| uuidc | This cookie is used to stores information about how the user uses the website such as what pages have been loaded and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This data is used to provide users with relevant ads. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | This cookie is set by Youtube. Used to track the information of the embedded YouTube videos on a website. |