‘Return to Dust,’ homegrown arthouse hit depicting rural life, gone from Chinese streaming sites

"Return to Dust" built buzz among Chinese moviegoers over the summer mainly through word of mouth, eventually becoming the top film at the local box office earlier this month. Now, it’s nowhere to be found on streaming services.

Return to Dust (隐入尘烟 yǐnrùchényān), a domestically produced arthouse title that has been a surprise box-office hit in China for its realistic portray of rural life in the country, has disappeared from all Chinese streaming services, likely a result of censorship.

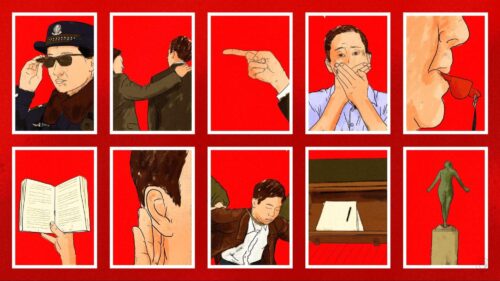

The issue was brought to people’s attention on Monday, when a slew of complaints surfaced on Weibo about the movie’s sudden removal from virtually all streaming sites in China, including major outlets like iQiyi, Tencent Video, and Youku. On Douban, a popular Chinese forum similar to Reddit and IMDb, short reviews seem to have been disabled, with the most recent comment time-stamped at around noon yesterday. (Although the official page of the film is still available.)

On Weibo, the hashtag #隐入尘烟# (Return to Dust) was unsearchable for a short period of time on Monday due to what the site cited as “relevant laws, regulations and policies,” which is the default explanation given for censorship of phrases on the platform. (As of the time of writing, the hashtag is viewable again.)

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

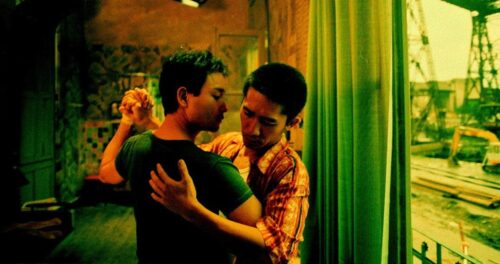

Written and directed by Chinese filmmaker Lǐ Ruìjùn 李睿珺, Return to Dust premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in February and has since been receiving heaps of praise from critics around the world. Set in a remote village in the northwestern province of Gansu, where Li was born and spent most of his formative years, the film centers on the tender love story between two middle-aged outcasts in the countryside — Cáo Guìyīng 曹贵英, who is disabled and suffers from chronic incontinence, and Mǎ Yǒutiě 马有铁, a humble farmer who owns nothing but a donkey for farm labor. Initially, the pair are pushed by their family members into an arranged marriage. But as time goes on, what seems at first like an odd relationship born out of nothing other than convenience gradually blossoms into a gentle late-life love and tender companionship.

The film itself isn’t necessarily radical or political, but because its main theme is rural Chinese life, the story inevitably touches on some subjects relevant to people living on the fringes of modern society and struggling in poverty, such as the authorities’ ruthless quest to acquire land to fuel urban development, a common goal among local governments that’s often achieved through exploitation of farm workers. In one memorable plot line that highlights the wealth gap between resourceful developers and powerless farmers, Ma and Cao, who are reluctant to ride their donkey for fear of overloading him, have to fend off a developer who drives a luxury car and wants to push them out of their home.

“The reality is, villages in China are shrinking, forcing farmers like Youtie to change their lifestyle, but it’s a necessary progression of modern society,” director Li told The China Project in March. “When a society develops, some enjoy experiencing the advances and the new technology, some don’t. I think this is a common problem with urbanization in the world, and perhaps one can’t offer a black-and-white solution. Think about this: while most people can enjoy technology, how come people like Youtie can’t enjoy all the good things that come with modern civilization? With this film, I wish to record the progression and make it available for others to reflect upon.”

Li also said he took pride in his commitment to authenticity and true-to-life portrayal of rural China in the movie. His earnest approach and choice of topic, which are hard to come by in Chinese films nowadays, as city dramas with star-studded casts tend to make more money, have, to many people’s surprise, paid off remarkably well in the domestic box office. While the film was met with a moderate response when it was released last July, the slow-burn title later proved to be a massive sleeper hit in the summer. In the first week of September, Return to Dust topped the Chinese box office in its ninth weekend of release, raking in nearly 90 million yuan ($12.5 million) before it left theaters.

So far, there has been no official explanation for why the film was pulled from Chinese streaming sites. On social media, speculation was rife that the film’s deception of rural life and social issues was so realistic that it hit a nerve with Chinese officials and censors. “Some people lack the courage to face the reality. Has art completely become a tool used by the ruling class in China?” a Weibo user asked, while another person fumed, “Some people’s suffering has been invisible in our society. Now that their struggles are shown to the public, some people have decided to hide the problem because it’s too real. Why are we doing this? Is it because we want the world to know that everyone in our society is well-off? Since that’s the official narrative, who dares to challenge it?” Another fan of the movie said, “I’d rather feel pain than be numb.”