The Formosa Incident: The protest that sparked Taiwan’s democracy

In the wake of widespread protests across China last month, the successes of Taiwan’s democratic protests in 1979 provide an interesting parallel.

This Week in China’s History: December 10, 1979

This week, we look at a moment when demonstrators — who were labeled dissidents by the government — demanded political and social change. The crowd, with students, professors, and journalists at their head, demanded freedom of expression, free public debate, and an end to one-party rule. But the party insisted such reforms would lead to chaos, and banned public discussion of the topic. Defying the ban, protesters took to the streets. As the protests grew in size, armed police and soldiers moved in, with orders to disperse them.

Comparisons with Beijing in 1989 — or even the past few weeks — are obvious. But this was the scene in 1979, in Taiwan’s second-largest city, Kaohsiung, where the Formosa Incident (or the Kaohsiung Incident) lit a slow fuse that would end single-party KMT rule on the island.

Over the last few weeks, protests in a dozen or more Chinese cities have challenged COVID-zero policies, some even calling for an end to Communist Party rule. The abrupt and tragic endings of previous protests in 1976, 1979, 1984, 1986, and 1989 naturally raised questions about the eventual fate of these latest protests.

At the same time, voters in Taiwan successfully tossed the ruling DPP out of power in local elections across the island. President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén), though she wasn’t on the ballot, even announced her resignation on November 26 when voters chose the opposition by a wide margin. The contrast between how “the people” can express their will was clear: a one-party authoritarian state on one side of the strait, a multi-party democracy on the other.

But it’s easy to forget that this is a relatively new development. Just a few decades ago, public expression on Taiwan was as difficult, and as repressed, as on the mainland. Perhaps more so.

The roots of that repression extend back to the start of KMT rule over the island. When Nationalist forces led by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) fled to Taiwan in the late stages of the Civil War, they took the institutions of the Republic of China with them to Taipei and housed them there. That included a legislature, called the Legislative Yuan. The members, elected from constituencies on the mainland, remained in their seats as part of the government in exile.

The KMT announced their time in Taipei would be short, while plans to retake the mainland were carried out. But as time went on, the legislators remained fixed, vestiges of a former polity. As long as they stayed on, there was no real chance for local representation in Taiwan’s government.

Additionally, following the 2-28 Incident of 1947, the KMT imposed martial law, outlawed rival political parties, and assumed broad powers to stifle dissent, further limiting opportunities for free expression. Martial law persisted into the 1950s…

…and the 1960s…

…and the 1970s.

Aside from repressing dissent, the persistence of a system intended to be temporary created some idiosyncrasies: Most seats in the legislature could not be contested, since their constituencies on the mainland lay beyond Taipei’s jurisdiction (as the incumbents aged, some were replaced by appointment, not election).

Local elections could be contested, though, along with seats representing Taiwan in the would-be “national” legislature. But with only one legal political party, there was little opportunity for an organized opposition that could set an agenda or challenge the government’s policies. However, candidates who were not part of the KMT could run as independents. (This had occurred since the early years of KMT rule. Wu San-lian (吳三連 Wú Sānlián) was elected mayor of Taipei as an independent candidate in 1951.)

But by the 1970s, frustrated with their inability to dissent or gain access to real political power, the movement began agitating for an end to single-party rule. An unofficial party of independent candidates and activists gained momentum, forming an “outside the party” (党外 dǎngwài) movement.

The ruling KMT alternated between toleration and suppression of them. In the summer of 1979, dangwai supporters began publishing Formosa magazine, which claimed to be ”the magazine of Taiwan’s democratic movement.” The magazine called for freedom of the press and an end to both martial law and one-party rule, sponsoring public events that, in turn, attracted the attention of the government. In early September, at a reception to launch the magazine at a Taipei hotel, about 1,000 “anti-communist heroes” disrupted the proceedings by throwing rocks and shouting obscenities, while police stood idly by. In early November, ax-wielding vigilantes attacked the magazine’s offices in Kaohsiung, destroying furniture and breaking windows; a similar attack followed later that month. Police refused to intervene; a third attack took place in a smaller branch office in early December.

To draw attention to their cause, and their predicament, dangwai activists planned a rally on December 10, designated by the UN since 1948 as International Human Rights Day. On December 9, organizers announcing the rally were pulled from their car by police, detained, and beaten overnight.

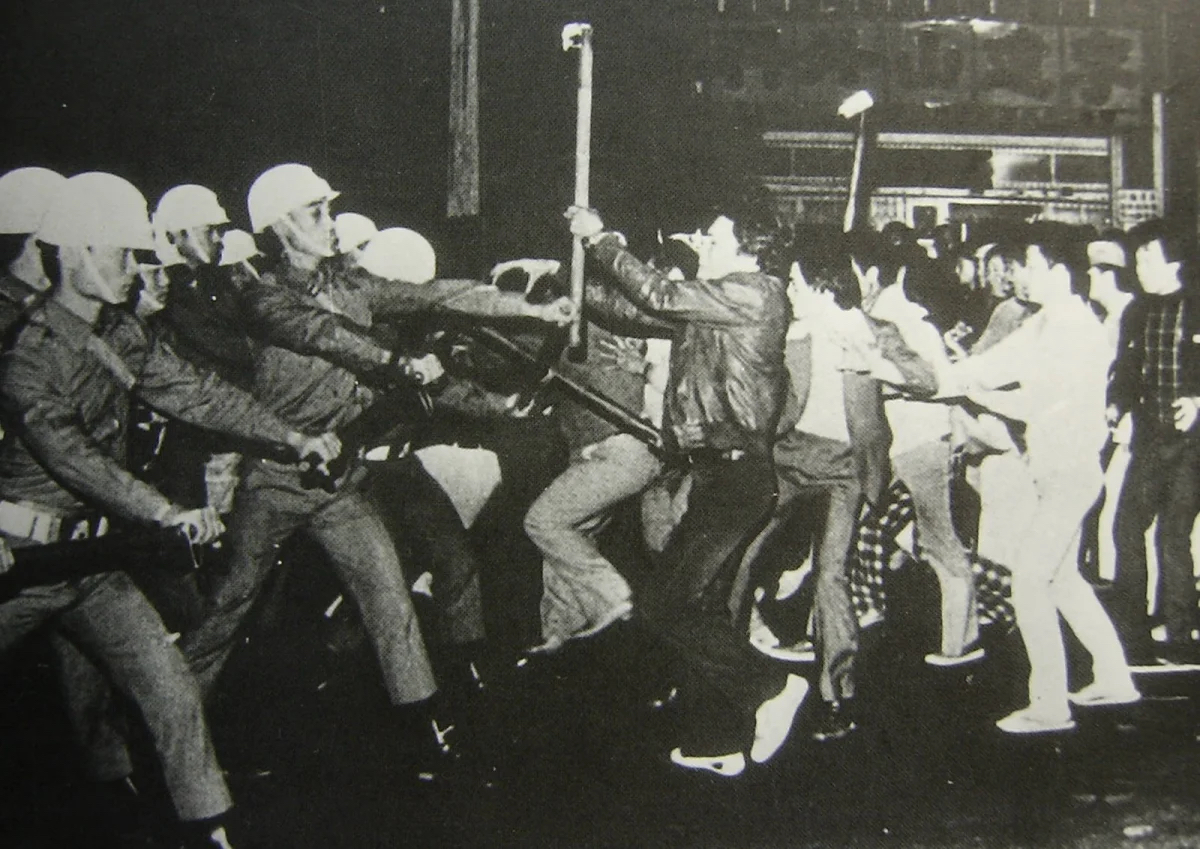

The following afternoon, when protesters began marching toward the planned rally in a local park, police blocked the way. The crowd was forced to double back on itself and eventually gathered in a traffic circle. By the evening, as many as 30,000 people had packed into the circle, surrounded on all sides by police in riot gear and riot-control vehicles. They fired tear gas into the crowd several times, starting at 8 p.m. and continuing until around 11 p.m. when police entered the square. A melee ensued, as police wielding billy clubs and tear gas battled protesters armed with sticks and bricks. More than 100 people were injured in the fight.

The next day, authorities arrested organizers and participants, holding them incommunicado until a trial in the spring. In two batches, the demonstrators were tried, convicted, and sentenced in what were widely seen as show trials.

The results were predictable: The participants were given sentences ranging from six years to life imprisonment. But the trials themselves changed the course of Taiwan’s political society. Under pressure, including pressure from abroad, courtrooms were opened to the public, bringing more attention to the movement than the demonstration had. In March, a New York Times op-ed declared “Freedom of expression remains a transitory thing in Taiwan.”

The demonstrations and trials were an unmistakable inflection point. Just months after those show trials, the ruling KMT agreed to permit non-KMT candidates to run for national elections, although no rival political parties were allowed. In December, dangwai candidates won 25% of the vote for the Legislative Yuan. Formosa’s organizers became the core of the first opposition party, the Democratic Progressive Party (the same party that was just voted out of power), in 1986. Martial law ended in 1987, 40 years after it was enacted. It would take another 14 years, but in 2000, Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁 Chén Shuǐbiǎn) — who had gained prominence as a member of the legal team defending the December 10 protesters — was elected as the first non-KMT president of the Republic of China.

The Formosa Incident, and all that followed, is a flaw in the CCP sophistry that representative democracy is a foreign invader doomed to destroy the country. It is also a reminder that the effects of protests and public criticism are often best measured not in days or weeks, but in years or even decades.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.