In Tainan, a lesser-known museum presents a de-sinicized version of the island’s history, and reveals a political divide over collective memory.

Most visitors to Taiwan don’t make it down to the southern city of Tainan — the island’s capital for more than two centuries — which is two and a half hours south of Taipei by high-speed rail. Even fewer make it to the National Museum of Taiwan History (NMTH), in a wetland area outside of the city center populated mostly by factories. Yet it is one of the most impressive museums I have visited.

Established in 2011, its exhibits present Taiwan’s history as waves of colonization and immigration, drawing a line between that history and the island’s current democratic and diverse society. Whereas other museums in Taiwan — such as the National Palace Museum, the National Museum of History, or the National Taiwan Museum (you’d be forgiven to mix them up) — were established under Japanese or Kuomintang martial law-era rule, the NMTH was one of the first national museums planned following Taiwan’s democratization, and the first to focus solely on the history of Taiwan and its people.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Chang Lung-Chih (張隆志 Zhāng Lóngzhì), the museum’s current director, said in an interview: “We’re talking more about the history of the land and the people, not about regimes, elites and rulers, anything like that. So it’s basically a bottom-up approach to Taiwanese history. Identity is not homogeneous … it is actually more frugal and dynamic, something in the making.”

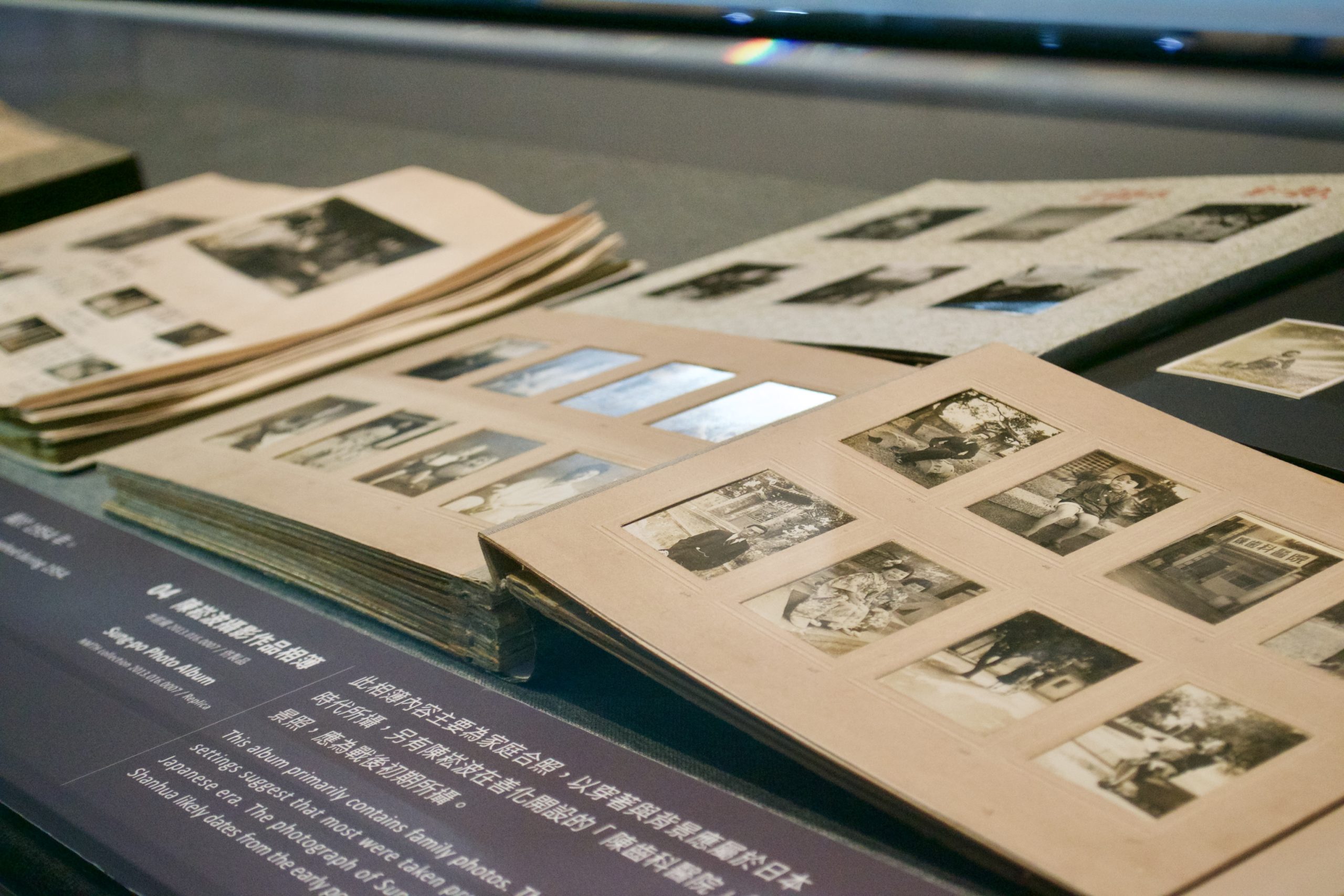

This has been achieved in part by letting museum-goers make the exhibits, contributing their own artifacts and interacting with them during visits. The museum has a collection of about 150,000 artifacts, a third of which were donated by the Taiwanese public.

The first thing you see when you step into the permanent exhibition is a large screen projecting images of museum guests onto the “Taiwanese portrait” — suggesting that anyone who arrives on the island can be Taiwanese. You can scroll through historical maps of Taiwan through the eyes of colonizers, and listen to the names of regions in indigenous languages.

In the section on Qing dynasty Taiwan — which details the complicated relationship between Taiwan’s indigenous peoples and Chinese colonizers — elders of Taiwan’s plains indigenous peoples, or Pingpu (平埔族 píngpǔzú) were invited to construct their own display to replicate a kuwa or meeting place for worship. The Japanese colonial era occupies the greatest space, featuring recreations of Japanese storefronts and a videogame in which visitors can play as an activist member of the Taiwan Cultural Association, a group that advocated for the independence of Taiwan at the time.

The permanent exhibit’s final section, on contemporary Taiwan, spotlights civilian activism and progress in areas such as environmental justice, LGBTQ rights, and transitional justice. It also features some of those artifacts donated by the people — such as a Tatung rice cooker and a New York Times ad purchased by Sunflower Movement activists in 2014 — and allows visitors to vote on which objects best represent certain ideas such as “home” and “Taiwan values.”

“Taiwan’s plural culture, ethnic diversity, spirit of tolerance and interaction between different groups,” said Chang Lung-Chih, “coincided with the emergence of civil society in Taiwan.”

During Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) administration of Taiwan (1949-1975), the Kuomintang (KMT, or Nationalist) party implemented a cultural policy of “Sinicization” that made Mandarin Chinese the official national language. Speaking other languages such as Taiwanese Hokkien or indigenous languages became a punishable offense. Chinese history was taught in textbooks, and the discussion or study of “Taiwanese history” was prohibited.

The lifting of martial law in 1987 and the subsequent democratization process marked a new surge in Taiwanese identity consciousness, as limits on free speech and expression — including the discussion of native Taiwanese culture, history and literature — were lifted.

Following democratization, the proportion of citizens who identify as solely Taiwanese have risen sharply, from 24.5% in 1996 (year of Taiwan’s first presidential election) to 62% in 2021, according to a poll from National Chengchi University. In the early 2000s, the education system underwent significant reform, and institutes for the study of Taiwanese history opened at Taiwan’s national research academy, Academia Sinica, and other universities across the island.

The National Museum of Taiwan History is an extension of this trend. The idea for a museum dedicated to Taiwan’s history was green-lit during the Lee Teng-Hui (李登輝 Lǐ Dēnghuī) administration in 1992, “out of the KMT’s early steps in the direction of ‘indigenization’ as it sought to bolster its democratic legitimacy in the early post-Martial Law era,” writes Edward Vickers of Kyushu University’s Asian Studies department.

Wu Mi-cha (吳密察 Wú Mìchá), who served as the museum’s director for several years of the planning process, described the museum as a “blue-green project” — an effort to unite ideas of the KMT (blue) and the opposition “green” Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Yet it took almost two decades for it to open, likely due to party leadership changes, and the struggle to strike a delicate balance on presenting Taiwanese history that would satisfy both sides.

One flaw of the museum is its lack of attention to the White Terror (1949-87), the period in which Taiwanese people’s freedom of speech, political expression, and movement was strictly limited under martial law. It’s an important facet of Taiwanese identity, but compared to other historical sections such as on Japanese colonization, the February 28 Incident and White Terror occupy notably little space, alongside a downplaying of the ongoing struggles of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples and discriminatory policies faced by the migrant worker population.

Historical memory, and how those memories should be portrayed at national sites, have been contentious issues in Taiwan. To pan-green Taiwanese, the National Palace Museum (housing artifacts from Beijing’s Forbidden City taken to Taiwan by the KMT during the Chinese Civil War) and the National Museum of History (with a collection relocated to Taiwan from Henan Provincial Museum) stand as reminders of the KMT’s attempts to “sinicize” Taiwan.

As the Taiwan Gazette noted in an interview with Chang Lung-Chih: “In Taiwan, people used to say that there is ‘no Taiwan in the National Museum of History, and no history in the National Taiwan Museum.’”

To push back against these narratives, the DPP-led government under Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁 Chén Shuǐbiǎn) approved the construction of a second “southern branch” of the National Palace Museum in Chiayi, southwest Taiwan, which takes a broader focus on Asian art. And national debate has begun to interrogate monuments like Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall, which pay homage to the former leader whom many Taiwanese remember as a dictator who orchestrated the White Terror.

A visit to that Memorial Hall or to the National Palace Museum, as compared to a trip down south to Tainan’s National Museum of Taiwan History, offers visitors a picture of two very different Taiwans: the former a sinicized, colonized island, the latter a nation that Taiwanese are continuing to build themselves. Yet that democratic, egalitarian dream is still in progress, haunted by the past.