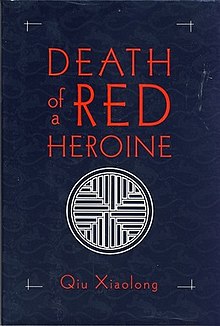

This is book No. 7 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“An engrossing first novel set in China during the 1990s that begins as a simple police procedural and then just keeps on getting more complex.”

—Kirkus

“Qiu Xiaolong knows that words can save your soul, and in his pungent, poignant first mystery he proves it on every page.”

—Chicago Tribune

“What’s so brilliant about this novel — apart from its hard-boiled, intricate plot and subtle characterizations — is its vivid picture of China in the 1990s on the verge of a historic shift into capitalism.”

—Newsday

“Qiu Xiaolong is one of the brightest stars in the firmament of modern literary crime fiction. His Inspector Chen mysteries dazzle as they entertain, combining crime with Chinese philosophy, poetry and food, Triad gangsters and corrupt officials.”

—Canberra Times

About the author:

Qiú Xiǎolóng 裘小龙 was born in Shanghai. The Cultural Revolution began during his last year of elementary school, essentially ending his formal education. He began studying English by himself in a local park. In 1977, after schools reopened, he enrolled at East China Normal University in Shanghai, and then the Chinese Academy of Social Science (CASS) in Beijing. After graduation, he worked at CASS as an associate research professor. He began to publish poems, translations (including of his particular favorite foreign poet, T.S. Eliot), and literary criticism.

In 1988, Qiu went to the United States on a Ford Foundation fellowship at Washington University in St. Louis, where he pursued his Eliot studies, obtaining a Ph.D. in comparative literature. In 1988 he decided to stay in the U.S., becoming a professor of literature and translation at WashU.

Following the success of Death of a Red Heroine, Qiu took the protagonist, Inspector Chen, and started a series of books, of which there are now a dozen. Recent novels include the inspector’s origin story, Becoming Inspector Chen (2020), which reflects back on his amateur investigations as a child during the Cultural Revolution and his very first case on the Shanghai Police Force. Later books have also dealt with more contemporary issues — for instance, a potential serial killer on the loose and environmental activists in Hold Your Breath (2021). Most recently, he has started to revive the Judge Dee franchise of mysteries, originally written by the Sinologist Robert Van Gulick, with The Shadow of the Empire (2022).

The book in 150 words:

The first book in the long-running, and still continuing, series featuring Inspector Cao Chen of the Shanghai Police Bureau’s Special Case Squad. It is the 1990s and Chen is in his early 30s and an amateur poet. Not your typical Shanghai copper. He is given charge of a high-profile murder case that rocks the city. Guan Hongying, the victim, was a National Model Worker, a Party member, a poster girl for devotion to the socialist ideal. But was she really a poster girl for anything wholesome? Inspector Chen soon finds out that his suspect list is comprised of people who just might be above the law. Chen discovers that his prime suspect, Wu Xiaoming, is the son of Wu Bing, a high-ranking Party cadre. Illicit affairs, political careers, and the go-go Shanghai world of the 1990s are captured to perfection in this opening novel in what became a best-selling series.

Your free takeaways:

Entrepreneurs, Chen observed, were springing up like bamboo shoots after a spring rain.

If you work hard enough at something, it begins to make itself part of you, even though you do not really like it and know that part isn’t real.

Justice in Shanghai was like colored balls in a magician’s hand, changing color and shape all the time beneath the light of politics.

“It’s the market economy,” Liu said. “The country is changing in the right direction. And the people have a better life.”

The episode came to him like an echo of his colleagues’ criticism: Chief Inspector Chen was too “Poetic” to be a cop.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Death of a Red Heroine is a police procedural, a not-unknown but generally uncommon literary genre in China and prone to censorship issues (no bent cops allowed!). Qiu Xiaolong’s genius was to pull off an insightful picture of 1990s Shanghai on the cusp of incredible changes within a story worthy of Chandler or Hammett and get a lot of people who would never ordinarily read a book about Chinese economic reform or Shanghai urbanization to buy an entire series detailing the process.

This was the first Inspector Chen book, so perhaps with hindsight the dialogue and plot do not flow as smoothly as they do in later entries in the series, after Qiu had had some practice. But the image of 1990s Shanghai in the first few Chens is most strong — Death of a Red Heroine was followed by A Loyal Character Dancer (2002), When Red is Black (2004), A Case of Two Cities (2006), and Red Mandarin Dress (2007). Others have followed, but these initial five in the series are the best for anyone looking to capture the smells, bells, and whistles of 1990s Shanghai in all its red-in-tooth-and-claw glory and rapid expansion.

Death of a Red Heroine and the early Inspector Chen books most vividly capture the atmosphere — and conflicts — of Shanghai’s transition toward a more capitalist economy while attempting to retain traditional Chinese values. Chen’s struggles are both with this new society and the still oppressive and overly bureaucratic government. Connie Fletcher, writing in Booklist, declared that the book was “fascinating for what it reveals about China as well as what it reveals about a complex man in this setting.”

The books have been dramatized by BBC Radio and also translated into Chinese. Despite it being completely obvious that Inspector Chen’s beat is Shanghai, the censors made Qiu change the name of the location to the supposedly anonymous “City H,” though nobody was fooled and the books remain popular in Shanghai. Naturally there has been some criticism of the novels from China — largely that they are overly focused on official corruption and written only with a Western audience in mind. Indeed, Chen’s uncovering of corruption while investigating cases does turn his idealism about the Chinese political system into pessimism.

However, for those that knew Shanghai in the 1990s and the massive (actual) turn-of-the-century scandals involving the mayor and Communist Party Secretary of Shanghai, Chén Liángyǔ 陈良宇, the world of Inspector Chen rings all too depressingly accurate.

Next time:

Time to step even further back, to the 19th century, to the conflict that came to define the adversarial relationship between the West and China — the Opium Wars. If we are to understand many Chinese grievances, the immense place of opium in Chinese history, and the notion of “Unequal Treaties,” how “the feelings of the Chinese people” were hurt first and foremost, then the two wars over opium need to be understood.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.