This is book No. 9 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“An indictment of Shanghai’s newly emerging industrialists which also tells of peasant uprisings, labor strikes, and rural depression.”

—New York Daily News

“Mao Dun paints a vivid and concrete picture of a time of upheaval in Chinese society. Mao Dun’s literary portrait of an important capitalist added a new touch to Chinese literature.”

—The European Science Foundation Project on Modern Chinese Literature

“Mao Dun desired, in theory at least, that his novels would be formally capable of accommodating all aspects of Chinese society, from the grossest abstraction to the minutest detail. After Lu Xun’s polished miniatures and the restricted scope of Ye Shaojun’s ‘sincere’ observations, this urge for comprehensiveness, and the fundamentally novelistic imagination that results from it (and that Mao Dun exhibits even in many of his short stories), must be recognized as something new in modern Chinese literature.”

—Marston Anderson, The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period

“One of the leading authors of the early-20th century May Fourth period, Mao Dun had a complicated relationship with both the Communist Party and the women’s liberation movement, and his fictional works reflect these twin concerns with revolution and gender.”

—Chen Jianhua, Revolution and Form: Mao Dun’s Early Novels and Chinese Literary Modernity

About the author:

Shěn Yànbīng 沈雁冰, a.k.a., Máo Dùn 茅盾 (1896-1981), was born in Zhejiang Province and was largely raised and educated by his mother. In 1913 he entered Peking University to study both Chinese and Western literature. Later he became a journalist, editor, and columnist, mostly expressing his social thoughts and criticisms. He was active in the May 4th Movement of 1919, and had various publications, translations, and promotions of Western writers in China, including Tolstoy, Chekov, Zola, Balzac, and Flaubert (influences of all can be detected in Midnight). He joined the Communist Party shortly after its foundation in 1921.

Following Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) repression of the left in Shanghai in 1927, Mao Dun sought refuge in Japan, returning several years later and joining the influential League of Left-Wing Writers. During this time he developed his signature style of realism as seen in Midnight, having spent many years observing the industrial situation in Shanghai silk filatures and cotton mills. In 1937 he joined the anti-Japanese resistance and then, after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, he was Mao’s secretary and Culture Minister until 1965. Mao Dun spent the Cultural Revolution under house arrest, but survived, and was rehabilitated.

He was elected chairman of the Chinese Writers’ Association in 1978. China’s prestigious literary prize, the Mao Dun Literature Prize, is named after him. His former residence in Beijing is now a museum.

The book in 150 words:

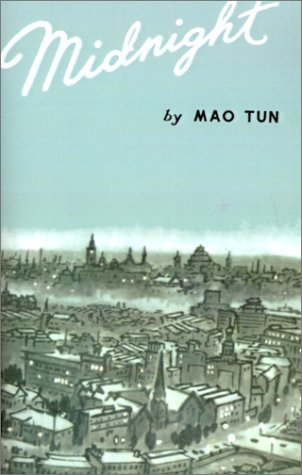

Originally published in 1933 and then published in English in 1957 by Foreign Languages Press, Beijing (translated by Hsu Meng-hsiung, later editions revised by Archie Barnes), Midnight (子夜 zǐyè)is generally regarded as Mao Dun’s masterpiece, a realist depiction of life in contemporary and cosmopolitan Shanghai. Mao Dun declared that literature should not be an “intoxication,” and though Midnight has been described as Shanghai’s “Vanity Fair” (after Thackery’s 1848 novel), it is a far tougher novel. Midnight shows treaty port Shanghai as essentially built on violence and corruption. The city’s great sits alongside low wages, awful conditions, and exploitation. This is Shanghai as a powder keg about to explode.

Your free takeaways:

The sun had just sunk below the horizon and a gentle breeze caressed one’s face…Under a sunset-mottled sky, the towering framework of the Garden Bridge was mantled in a gathering mist. Whenever a tram passed over the bridge, the overhead cable suspended below the top of the steel frame threw off bright, greenish sparks. Looking east, one could see the warehouses of foreign firms on the waterfront of Pootung like huge monsters crouching in the gloom, their lights twinkling like countless tiny eyes. To the west, one saw with a shock of wonder on the roof of a building a gigantic NEON sign in flaming red and phosphorescent green: LIGHT, HEAT, POWER.

China was not traveling the capitalist road; but under the exploitation of colonial and feudal powers, allied with the bureaucrat-compradore class, China was sinking deeper into a semicolonial, semifeudal condition.

On a Shanghai amusement park:

They’ve got good wine and good music, and there are White Russian princesses, prince’s daughters, imperial concubines and ladies-in-waiting to dance attendance on you. Green, shady trees and lawns as smooth as velvet. And then there’s a little lake for boating…ah, it reminds me of the happy hours I spent on the banks of the Seine.

Wu Sunfu, an industrialist and a Nationalist, desires to rebuild his home village of Shuangqiao into a model town:

With a forest of tall chimneys belching black smoke, a fleet of merchantmen breasting the waves, and a column of buses speeding through the countryside.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

The subtitle given to Midnight in its first English translation, “A Romance of China,” may appear odd given that the novel is a searing indictment of capitalism in the International Settlement of Shanghai between the world wars. But Mao Dun was one of a number of contemporary modern Chinese writers who were left-wing, embraced realism, and wanted to write in the way that people spoke rather than the more highfalutin, classical style. They wanted to be more modern, and a great number of them naturally gravitated toward China’s most modern city, Shanghai.

In order to create a contemporary Chinese literary phenomenon — which would coalesce around the works of Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅, Bā Jīn 巴金, Lǎo Shě 老舍, and others — the words they wrote had to be published. And in the Shanghai International Settlement, there was considerably less censorship compared to the rest of China. Outside the “protection” of the foreign concessions, a lot of the books that they were writing would have been censored. The nascent Chinese film industry centered itself in Shanghai for the same reasons, and the Chinese newspaper industry in many cases had its head offices in Shanghai with papers registered there, or as far away as the United States, to avoid censorship. This is the conundrum of Shanghai: it was a semi-colonial, rapaciously capitalistic city, yet somewhere that provided left-wing creatives with room to breathe and express themselves. And this is the Shanghai Mao Dun critiques so forensically in Midnight, with themes of class conflict and historical development, from a Marxist perspective.

Mao Dun’s is not the only, but it is one of the grittiest portrayals of Shanghai written in the 1930s — we could call upon foreign writers such as Andre Malraux, Maurice Dekobra, and Riichi Yokomitsu (and may in future articles), and the likes of Ba Jin and Lao She within China. Mao Dun’s work has stood the test of time and deserves more recognition overseas. It was not immediately translated in the 1930s — non-Chinese readers had to wait till the late 1950s to read the novel (perhaps one reason the Shanghai treaty port authorities never banned it in the way they did books they could easily read, such as DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and James Joyce’s Ulysses, which they deemed too erotic or too left-wing).

Midnight looks at the two sides of the Chinese experience in Shanghai: the terrible and awful conditions in the factories that led to the organization of trade unions and socialist and communist parties; and, on the other side, the incredibly wealthy class of Shanghainese. Probably three million of Shanghai’s population of four million at the time were completely impoverished or on the breadline, but the wealthiest Chinese in China also lived in Shanghai. Mao Dun shows both those sides: the ones that are starving and losing fingers and eyes in the factories for pennies, and these others who are sending their feckless children off to university at Cambridge, living in great houses in grand splendor. They are also adopters of Western culture in what they’re reading, studying, wearing, and often worshipping.

There are issues with the novel, particularly some that appear more obvious to contemporary readers. Mao Dun’s representation of women is sometimes problematic. In Midnight, women are relegated to distinctly second-class characters and a somewhat caricatured femme fatale. In the years after the May 4th Movement, Mao Dun accentuated positive female characters — New Women — but by the 1930s this approach slipped somewhat.

Still, Midnight is a crucial text for a number of reasons and deserves its prominent place on the Ultimate China Bookshelf. It is an excellent (and today under-read) example of the left-wing school of novelists at work in Shanghai in the late 1920s and 1930s. It is also a work by an avowed communist that avoids the bland landscape of the socialist-realist novel that would come to dominate. At the same time as being critical of semi-colonial Shanghai, it is, especially in the first third of the novel, an unabashed hymn to the glories of the “modern” (módēng 摩登) in the city — Citroen cars, radios, foreign mansions (fǎng yáng 纺洋), guns, high heels, beauty parlors, jai alai, taxi dancers, movie stars, silver ashtrays…It is an image, and a contradiction, of Shanghai that resonates down to the second decade of the 21st century.

Next time:

Mao Dun’s searing indictment of Shanghai’s naked capitalism and exploitation hit a chord with many on the left in China and globally. Other novels also examined Shanghai, often from a more outsiders’ perspective. Since the Second Sino-Japanese War, and World War Two generally, relations between China and Japan have been poisoned. All too often the enormous interchange — academic, artistic, political, diplomatic, military — between the two countries has been overlooked, even arguably purposefully obscured to reinforce the current narrative. But the interchange was substantial and ran both ways — for instance, both Sun Yat-sen (孙中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) and Chiang Kai-shek spent time in Japan. So perhaps it is worth considering another great novel of Shanghai, slightly earlier than Mao Dun’s, by a Japanese author.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.