This is book No. 11 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

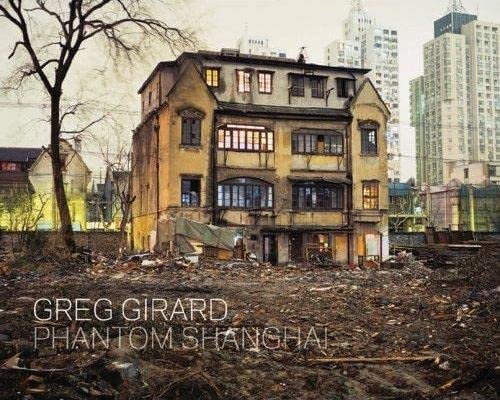

“There are countless photography books on contemporary China in general, but this one focuses on the rapidly changing nature of Shanghai, juxtaposing traditional buildings with the skyscrapers that are shooting up.”

—The Independent (London)

“Girard’s work looks beyond the gleaming skyscrapers of new Shanghai to the old city, to the lane neighborhoods that leave one family living beside a half-demolished building that has become the area’s garbage pile.”

—The Province (British Columbia)

“Because he’s an outsider Girard has a little wiggle room. And in every Shanghai bookshop his Phantom Shanghai is prominently featured. It touched an emotional chord with Shanghai people.”

—National Post (Canada)

About the author:

Greg Girard is a Canadian photographer who has spent much of his career in Asia. His work has examined the social and physical transformations in Asia, especially in its largest cities. Along with Phantom Shanghai, Girard is perhaps best known for his book (now a serious collector’s item) City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City, with co-author Ian Lambot (1993). An updated version, City of Darkness Revisited, was published in 2014.

Girard was based in Shanghai between 1998 and 2011. Other collections of his photography include Under Vancouver 1972-1982 (2017); HK:PM. Hong Kong Night Life 1974-1989 (2017); Hotel Okinawa (The Velvet Cell, Osaka, 2017); Hanoi Calling (2010); and In the Near Distance (2010), a book of early photographs made in Asia and North America between 1973 and 1986.

His photographs have appeared in National Geographic Magazine, the New York Times Magazine, Time, Fortune, the Sunday Times Magazine (UK), and others.

The book in 150 words:

Greg Girard’s Phantom Shanghai is a visual telling in 130 photographs (published by the Magenta Foundation) of the almost wholesale eradication of the physical Shanghai we encountered in our previous two Ultimate China Bookshelf books — Mao Dun’s Midnight (1933) and Riichi Yokomitsu’s Shanghai (1928) — the street-by-street, lilong-by-lilong, shikumen-by-shikumen loss of the old city and many modernist and art-deco treasures. The book includes a foreword from cyberpunk author William Gibson (best known perhaps for Neuromancer), who speculates on the notion of erasing almost an entire pre-existing city to build anew. Girard began his project in 1998 with the express intent of capturing a Shanghai that was unlikely to survive its own vision of urban development.

Your free takeaways:

Shanghai — a city in the process of dismantling its history to accommodate China’s new cosmopolitan vision of itself.

Violence is not the wrong word to describe what happens when there are no impediments to change. There is a sense that this place is disappearing, a place I very much wanted to explore.

These are photographs of Shanghai that will not survive the vision the city has for itself. That these homes, shops, lanes, and buildings survived as long as they did, and in the way that they did, is by accident rather than design. Whatever the utility of this partial and very subjective record, my intentions, as much as I understand them, have little to do with architecture or preservation. I’m not an historian or an architectural photographer. But I do want to make photographs that show what a place, this place, looks like when it’s used in this way. Here is Shanghai’s “lived-in-ness,” the vanishing evidence of the hard flow of time through this city.

From the outside many of these places can look quite grand, in a faded sort of way, but on the inside the conditions can be quite dire. A general lack of upkeep over the decades has given them a patina comprised of layers of peeling paint, dust and cooking grease. So, I wanted to show the insides of these places and what was a very normal way to live for a couple generations of Shanghainese: the shared kitchens and bathrooms, the relative lack of privacy, the sense of lived-in-ness.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:We should never forget that every truly great China bookshelf needs a few coffeetable books nearby — the visual arts are important to us too, of course. There are any number of great photo books of China we could include (and may at later dates), such as Magnum China (2018, edited by Colin Pantall and Zheng Ziyu), Jack Birns’s Assignment: Shanghai (2003) of late 1940s images, and H.S. Liu and Karen Smith’s Shanghai: A History in Photographs, 1842 – Today (2011). Some photography books though have been especially crucial to our better understanding of Shanghai and its almost unique history and development: for instance, James Bollen’s Jim’s Terrible City (2014) that attempted to view the contemporary city through the eyes of former Shanghailander-turned-avant-garde author JG Ballard. Meanwhile, Tess Johnston’s A Last Look: Western Architecture in Old Shanghai from 1993 provided a remarkable catalogue of remaining Shanghai architecture from the treaty port era, just as much of it was meeting its final fate of bulldozers.

Cataloguing that destructive process — running from the 1990s boom years of the Jiāng Zémín 江泽民 administration (see Book No. 3, Wily Lo-Lap Lam’s The Era of Jiang Zemin) to the immediate run up to the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai — makes Greg Girard’s Phantom Shanghai all the more important as a vital historical record. That Girard does it so aesthetically, his images highlighting the contrasts between high- and low-level density housing, electric light seen through the remaining few windows of old Shanghai where once vibrant, multi-generational life dwelt, made Phantom Shanghai a masterpiece worthy of our Ultimate Bookshelf.

It’s a neat trick to convey human stories through photographs that have few human beings in them, yet Girard manages it. The photos, which may appear stark and almost unbelievable to anyone who arrived in Shanghai after 2010, chart the human cost of Shanghai’s “modernization.” Girard himself has said, “You’re looking for ever more intimate things. Ever closer, deeper, more private, more personal.”

Many went quietly, and happily, to their new highrise homes. But many were not happy about compensation rates or the non-negotiable nature of relocation and demolition, while others cited attachments to their homes, long family lineages, and even occasionally architectural preservation. But nothing was to get in the way of government-mandated mass clearances. It still continues of course — what’s left of historic Laoximen and the old city is being cleared as you read this — but the scale of the late 1990s and early 2000s was without precedent.

In his brief but well-crafted introduction to the book, William Gibson notes, “Liminal. Images at the threshold. Of the threshold. The dividing line. Something slicing across accretions of cultural memory like Buñuel’s razor…Documents of the gone world.” I think Gerard largely began to photograph what was around him — those vast tracts of bulldozed and flattened rubble with nothing but the odd, surviving house were so commonplace to those who lived in Shanghai in the 1990s and the turn of the century. But they didn’t last long. The next crew arrived and a highrise apartment block, a mall, an office complex were built as subway lines proliferated and radiated outwards to the then-far-flung districts of northern Hongkou, far eastern Yangpu, the world beyond Xujiahui, and even that remote (mentally and physically) never-world of Pudong.

Shanghai, like many cities (think mediaeval Paris replaced by Hausmann, for instance), is a series of layers. A walled fort alert to Wukou pirates morphs into a colonial possession of 19th-century aggressors, to a modernist city of cosmopolitans, to a drab town of Maoism, to a new and exploding mega-city. Post-COVID, perhaps Shanghai is now beginning to revolve through another iteration, and so much that was built on the ruins Girard captured in his work will be repurposed, refabricated, and perhaps demolished once more to be replaced.

Next time:

Toward the end of the 20th century, Beijing too was going through violent political upheavals as well as its own tumultuous encounter with the bulldozers. Life was upended for so many — hutong dwellers, new migrants, young people trying to find their place in the new China of haves and have-nots, glitzy malls, ring roads, and political freedoms (within strict limits). One writer came to symbolize this period more than any other, a writer who declared, “I am a hooligan, who should I fear?”

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.