This Week in China’s History: April 27, 1911

In the early morning hours of April 27, 1911, Lín Juémín 林觉民 wrote to his wife, Chén Yìyìng 陈意映. The next day, he would be part of an uprising that would — he hoped — overthrow the Qing dynasty, but he held out little faith that he would survive. “As I write, I am a man in this world; when you read this, I shall already be a ghost.”

What had brought Lin to this desperate state was the country he observed collapsing all around him. Death was not something that could be avoided; it was just a question of which of the many calamities facing the country would take its toll. His generation, he wrote to Yiying, faced “death from natural disasters; death from bandits and robbers; death from the foreigners slicing China apart; death from corrupt officials. In China, we may die at any time and in any place.”

As Lin wrote, there were just a few hours before the planned uprising, but such sentiments had been building in Qing China for some time. Starting in 1895, there had been no fewer than 15 organized uprisings against the dynasty, each one thwarted by the authorities, their participants jailed, executed, or sent into exile. This time, organizers were confident of success, buoyed by wealthy overseas backers, battle-tested leaders, and guns and ammunition smuggled from abroad.

Historian Linh Vu, in her book Governing the Dead, described what happened next, as “a group of local gentry, businessmen, overseas students, and secret society members armed with pistols and explosives smuggled from Hong Kong broke into the residence of the viceroy of Guangdong and Guangxi,” determined to bring down the Qing dynasty.

Leading the insurrection was General Huáng Xìng 黄兴, a veteran revolutionary and renaissance man who had earned a jìnshì 進士 — the highest rank in the Qing civil service exam — in 1893 (and would later be portrayed by Jackie Chan in the 2011 film 1911). Like many future leaders, he studied abroad in Japan — handpicked by reformer Zhāng Zhīdòng 张之洞 — studying military tactics and strategy along with his more conventional curriculum. Returning to China, he became active in anti-Qing movements, including a 1903 uprising that was discovered by authorities, who forced Huang to flee back to Japan.

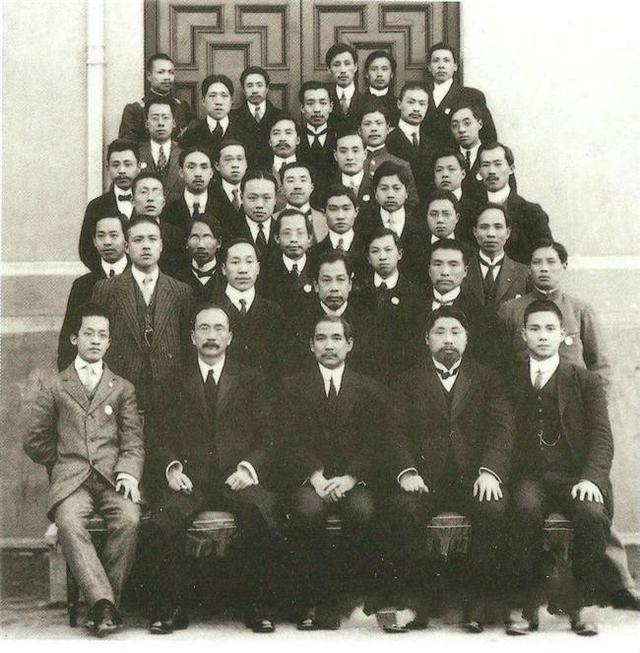

It was during that second sojourn in Japan that Huang met Sun Yat-sen (孙中山 Sūn Zhōngshān). Bonding over their shared commitment to overthrowing the Qing through republican revolution, the two men unified their forces to create the Revolutionary Alliance in 1905. The Revolutionary Alliance brought together the largest anti-Qing groups into an umbrella organization that had little ideological unity other than opposition to the Manchus, who they viewed as weak, corrupt, and incapable of defending China against foreign incursions (or, worse, complicit in it).

Huang was second only to Sun in leading the organization, and he developed a robust revolutionary network throughout East and Southeast Asia. Returning to China in 1907, Huang became the leader of the southern branch of the Revolutionary Alliance at Sun’s request, and focused on planning an uprising in Guangzhou, but maintained his ties to Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.

The burden of knowing the past is that we know what happens next: Sun would lead a successful revolution to bring down the Qing dynasty, becoming known on both sides of the Taiwan strait as the father of modern China. Yet in the fall of 1910, Sun and Huang were running out of chances. They had led nine failed uprisings against the Manchus. Convincing backers to finance the revolution became more difficult with each failed attempt.

Agents of the Qing government were continually hunting down rebels, and had managed to have Sun declared persona non grata in much of the region. Fleeing Hong Kong for Singapore, where pressure eventually drove him out of that colony as well, Sun finally set up a base of operations at 102 Armenian Street, in the Georgetown neighborhood of Penang in Malaysia, under the guise of a reading club, where he would gather support for what he believed would be the decisive battle, the insurrection that Lin Juemin was preparing for as he wrote to his wife.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

On November 13, Sun gathered together some of the most prominent members of the local Chinese community and made what he said was a last plea for more support. Though the revolution had not yet succeeded, he told a dozen or so men that the Qing was on the verge of collapse. He needed one last chance, and if he failed, Sun declared, “I will not trouble you again.”

The speech worked. Sun raised several thousand dollars on the spot and began planning the uprising that Sun assured supporters would topple the hated Manchus. A date was set for April, 1911, and networks across East Asia went into action, buying guns and explosives in Japan, Hong Kong, and China and smuggling them to Guangzhou.

After an additional delay, plans went into action on April 27. Huang Xing led nearly 100 revolutionaries, including Lin Juemin, to capture the Qing viceroy of Liangguang — i.e., the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi — as a first step to taking the city. From there, the revolt would spread quickly as the brittle dynasty crumbled.

Fueled by surprise, the plan began well, but soon went awry, in part because plans for the uprising had leaked to the authorities. The Qing viceroy, Zhāng Míngqí 张鸣岐, escaped, and soldiers confronted the rebels. Dozens of rebels were killed in a firefight, and most of those who survived were arrested and executed (Huang Xing, who escaped with gunshot wounds, was an exception). Nearly all of the 120 or so revolutionaries who embarked on the attack were killed. Eighty-six bodies were recovered, but of those, only 72 could be identified.

Despite Sun’s assurances, the uprising — like so many before it — had failed.

But the story of the uprising did not end there. Local officials planned to ignominiously dispose of the bodies, dumping them in a burial ground used for common criminals, but two participants intervened and managed to have the 72 buried in a nearby park. As historian Vu describes, “The site, with its simple graces, became the Yellow Flower Hill,” and the uprising came to be known, ironically, for the site that was a visual reminder of its failure. When the greater revolution eventually succeeded — following the October Wuchang Uprising — Yellow Flower Hill became a nationally sacred site.

The rebellion itself accomplished little, but its legacy became important, not only to the revolution but in popular culture even to the present, exemplified by the 2011 Hong Kong film 72 Martyrs. As Vu writes, “Instead of being condemned as criminals, these insurgents came to represent the ideal citizens of the Republic of China.”

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.