This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

When she first began painting, Shāng Liàng 商亮 created carefully arranged, realistic depictions of everyday scenes in a mild color palette. Fifteen years later, her works have different air: one of abnormal power and force. She paints muscular characters that seem to burst out of the frame of her large canvases. They can be human or inhuman, but they all possess the same larger-than-life muscles.

Born in 1981 in Beijing, Shang was raised in a military community in the same city. She attended the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), where she studied oil painting under Liu Xiaodong, one of China’s greatest painters. Several years later, searching for new means of expression, she returned to CAFA for a master’s degree in experimental art, and there she developed a distinctive, slightly surreal style.

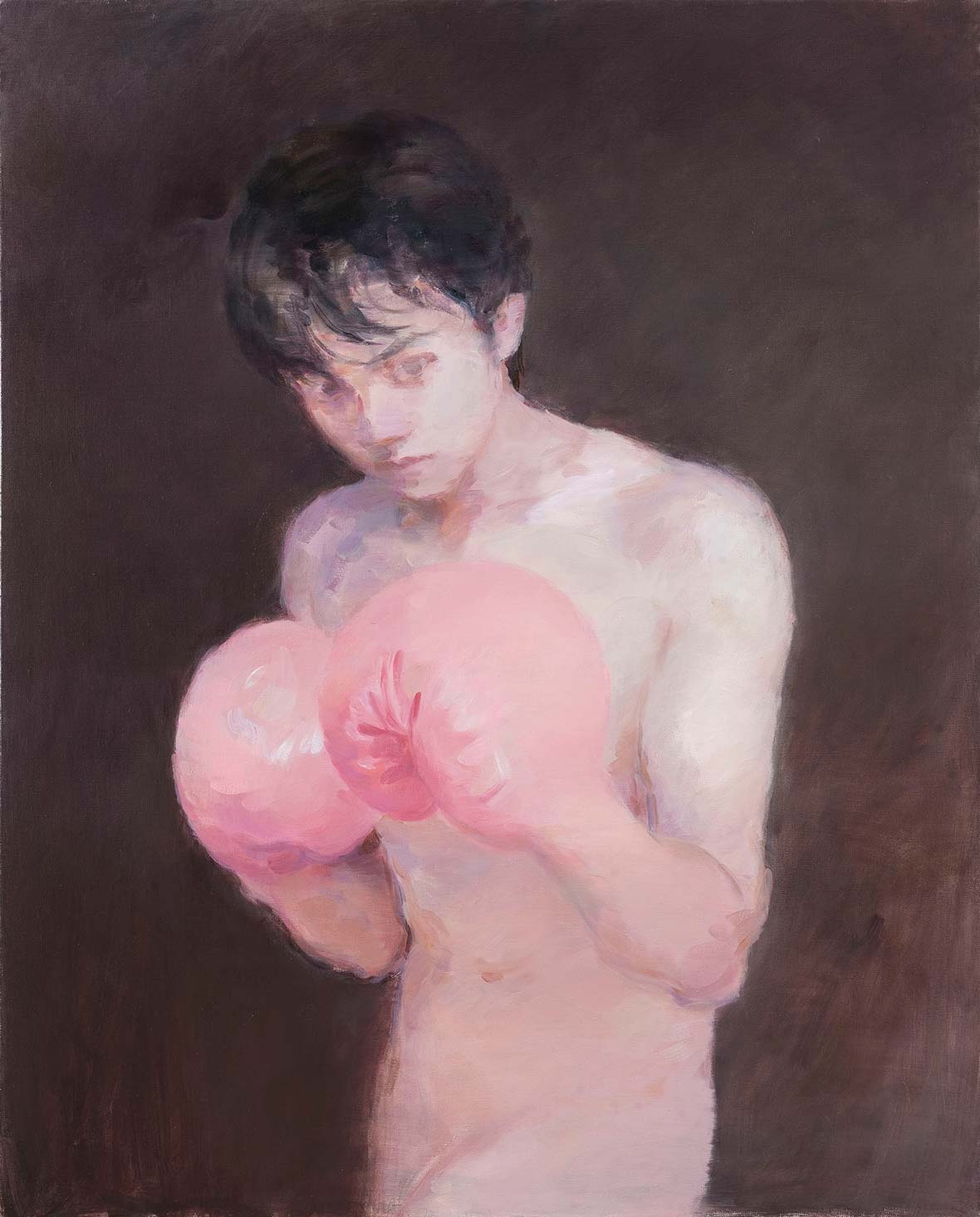

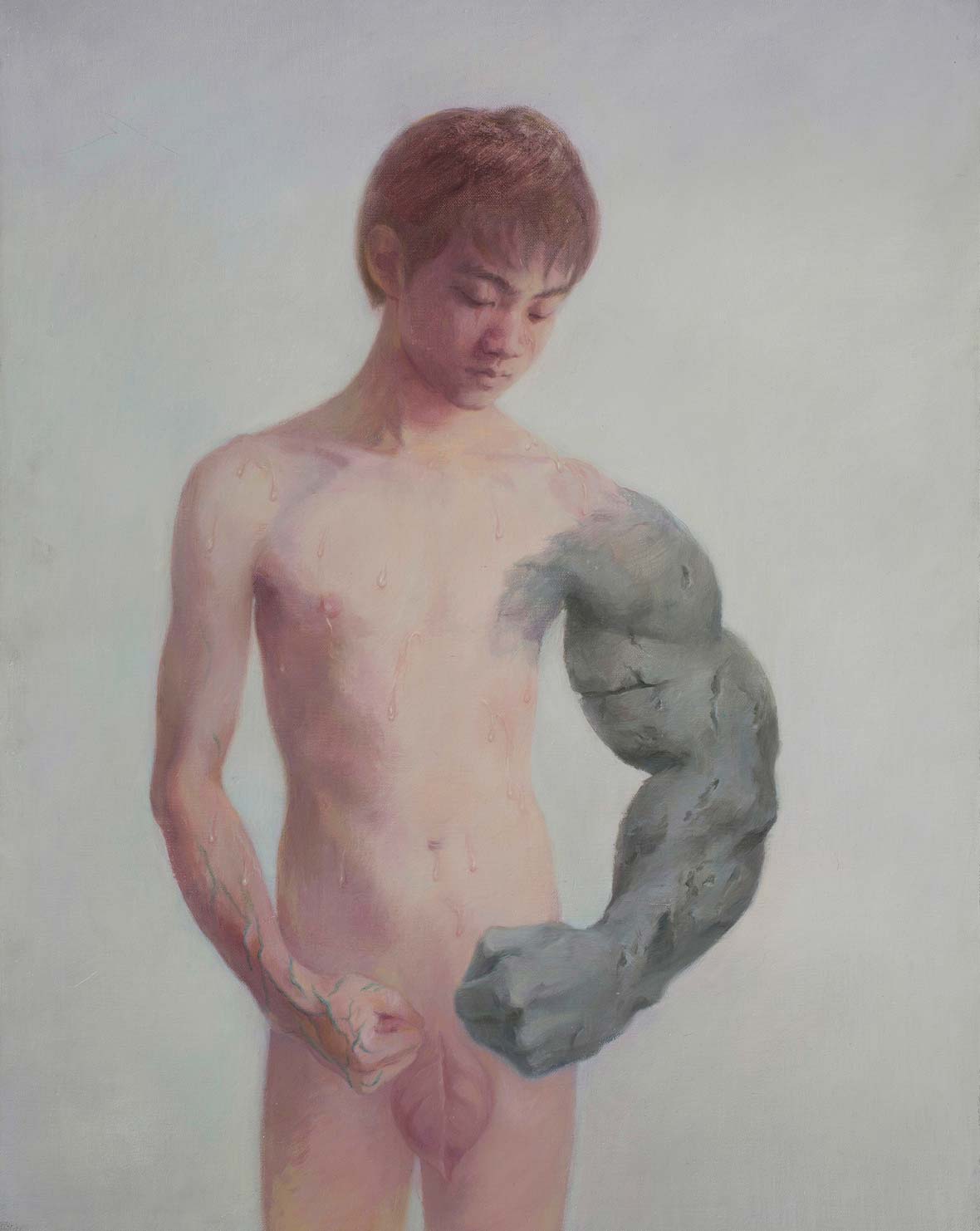

This distinctive style began to appear when she became interested in the subject of adolescence: “I think there is obscurity about this period in life,” she explains, “teenagers have confused emotions and uncertainty about what they will become. It’s a period of intense transformation and development, both in the body and the mind.” More than anything else, adolescence is an important moment for developing a moral sense. Teenagers are complicated beings, innocent and still quite vulnerable to the influences around them.

In 2012, Shang began to work on The Real Boy series, portraying slender teenage boys with hypertrophic abdominals, chests, and arms. Some are flexing their muscles so hard that veins pop out on their skin. Their faces still reveal tenderness and immaturity, but their expressions and body language suggest a longing to become powerful, muscle-bound men.

Some paintings in this series feature boys with long, pointy noses, a clear reference to Carlo Collodi’s classic children’s tale Pinocchio. Like the puppet who dreamed of becoming a real boy, the characters in these paintings have to prove themselves mature without straying from the path of honesty and morality. This series dramatizes the challenges and conflicting impulses of adolescence.

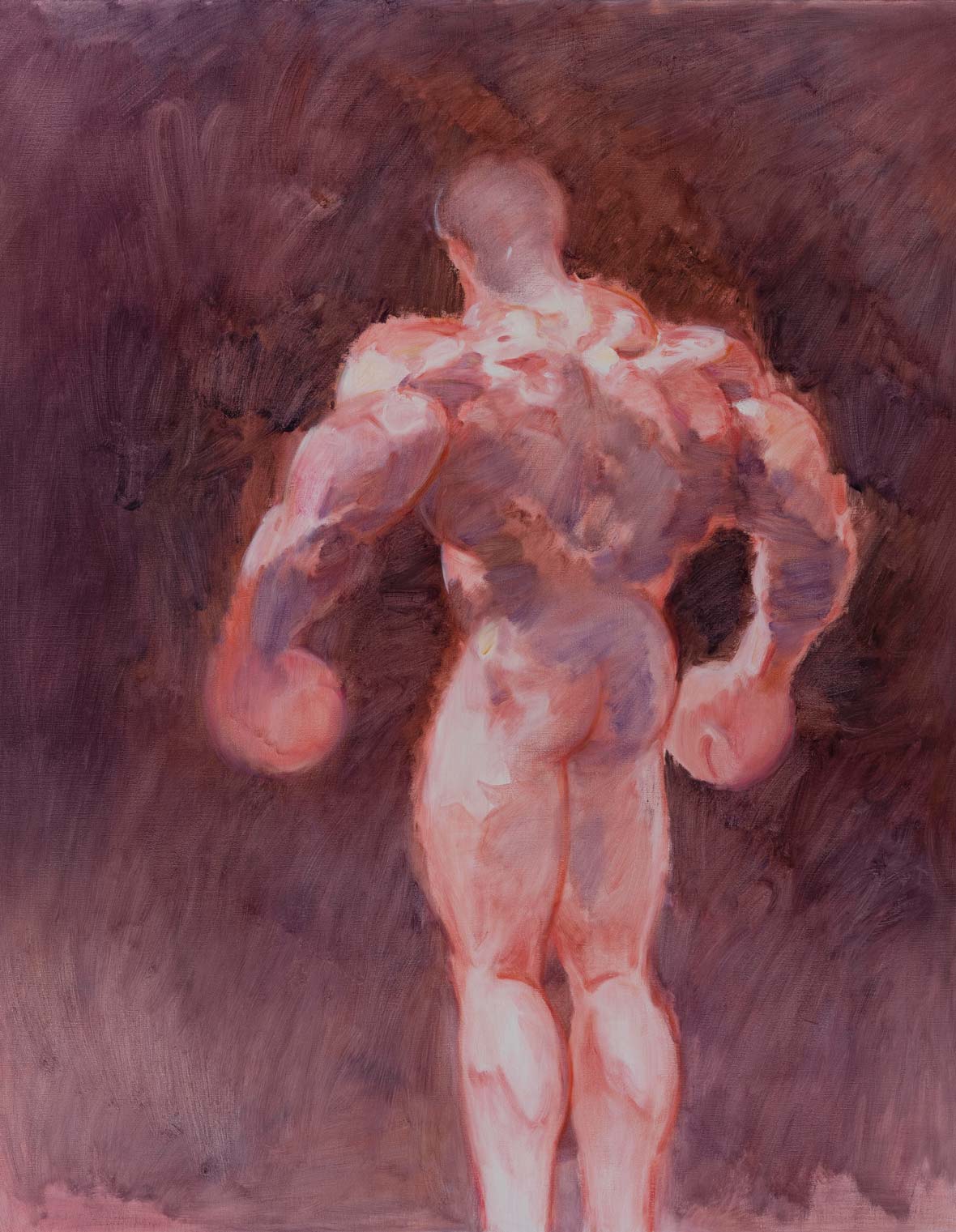

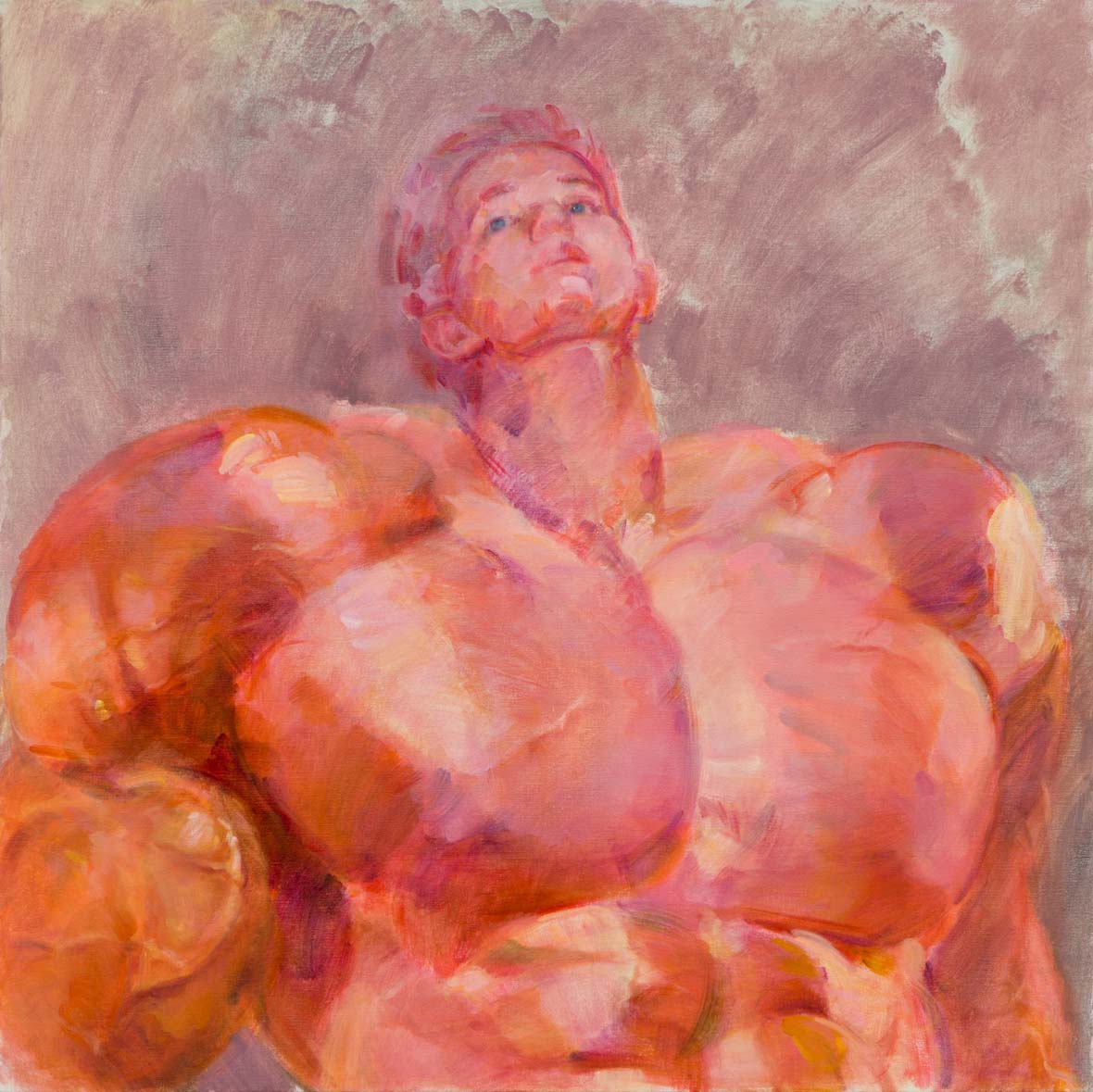

Shang’s following series, Good Hunter, developed naturally from The Real Boy: it’s as if the same characters had grown both in physical form and in confidence. The new characters seem to have exaggerated internal strength, with bodies developed into cartoonish muscular form. Their faces, however, retain the same boyish expressions or have no expression at all. The oversized canvases, bigger than a human body, suggest an intimidating superhuman strength. Standing before these characters, the viewer may feel small, or even oppressed. The exaggerated manliness combined with a complete absence of women seems to be an allusion to patriarchal systems built on oppression and misogyny.

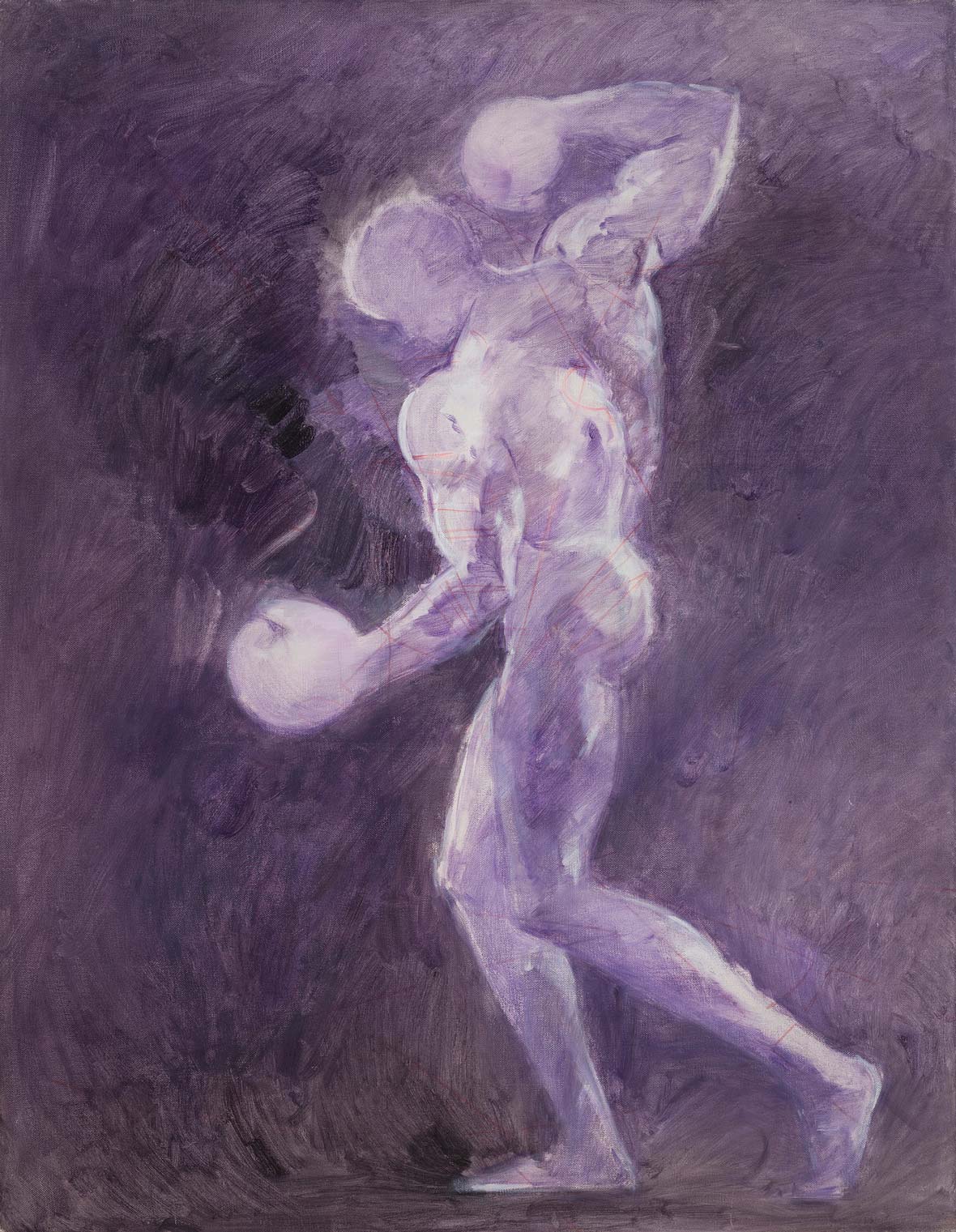

In Boxing Man, her latest series, Shang departs completely from realistic human anatomy, and a new character emerges: one with a boxing glove in the place of the head and no sexual organs. None of her characters ever really have an adult face, and here they are frightening and inhuman creatures. As she explains: “It’s not human. It’s a new species. You can guess how it senses the world, what it feels, and what it thinks.” With the metaphor of strength and power becoming a head on their own, Boxing Man appears as the culmination of all underlying issues found in her previous series: the struggle for the ultimate strength, the torture of moral dilemmas, and the blind pursuit of power.

As references for her characters, Shang looks to bodybuilding and fighting TV shows. She also refers to classical sculptures by Michelangelo. To achieve a certain luminosity, she places different layers of paint one over the other. Red, dark-red, and brown are predominant colors, evoking oxygenated and deoxygenated blood and bruises. Her brushstrokes have a notable strength, which comes, no doubt, from her practice of Chinese calligraphy. There are also elements of taiji embedded in the movements and curves of the characters.

Although she has unconsciously absorbed traditional Chinese elements, Shang’s underlying subject matter is not specific to any country or culture. Her work can be seen as a critical commentary on traditional ideas of masculinity. It is fascinating that this appraisal comes from a female artist. If boys face excruciating difficulties when expected to assume the role of a man, what do girls feel when they, too, are expected to succeed?

Like this story? Follow neocha on Facebook and Instagram.

Website: shangliang.co

Contributor: Tomás Pinheiro

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li