This is book No. 20 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“The best thing we have had on the Chinese character and temperament, and so delightfully done that it makes intensely interesting and stimulating reading. Not the conventional study of the Chinese merchant, the Chinese philosopher, the Chinese warlord, the Chinese farmer, the Chinese coolie — but a study of the forces that build this facet and that of the reasons for China’s long sustained history, the reasons he has faith in her working gradually to the fore again.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Mr. Lin Yutang has published a classic; and shown himself to be a philosopher and an original — in a class by himself, and a very high class — just as definitely as Shakespeare or Kipling.”

—The Edmonton Bulletin

“Of his many English-language books, My Country and My People was widely translated and for years was regarded as a standard text on China.”

—Britannica

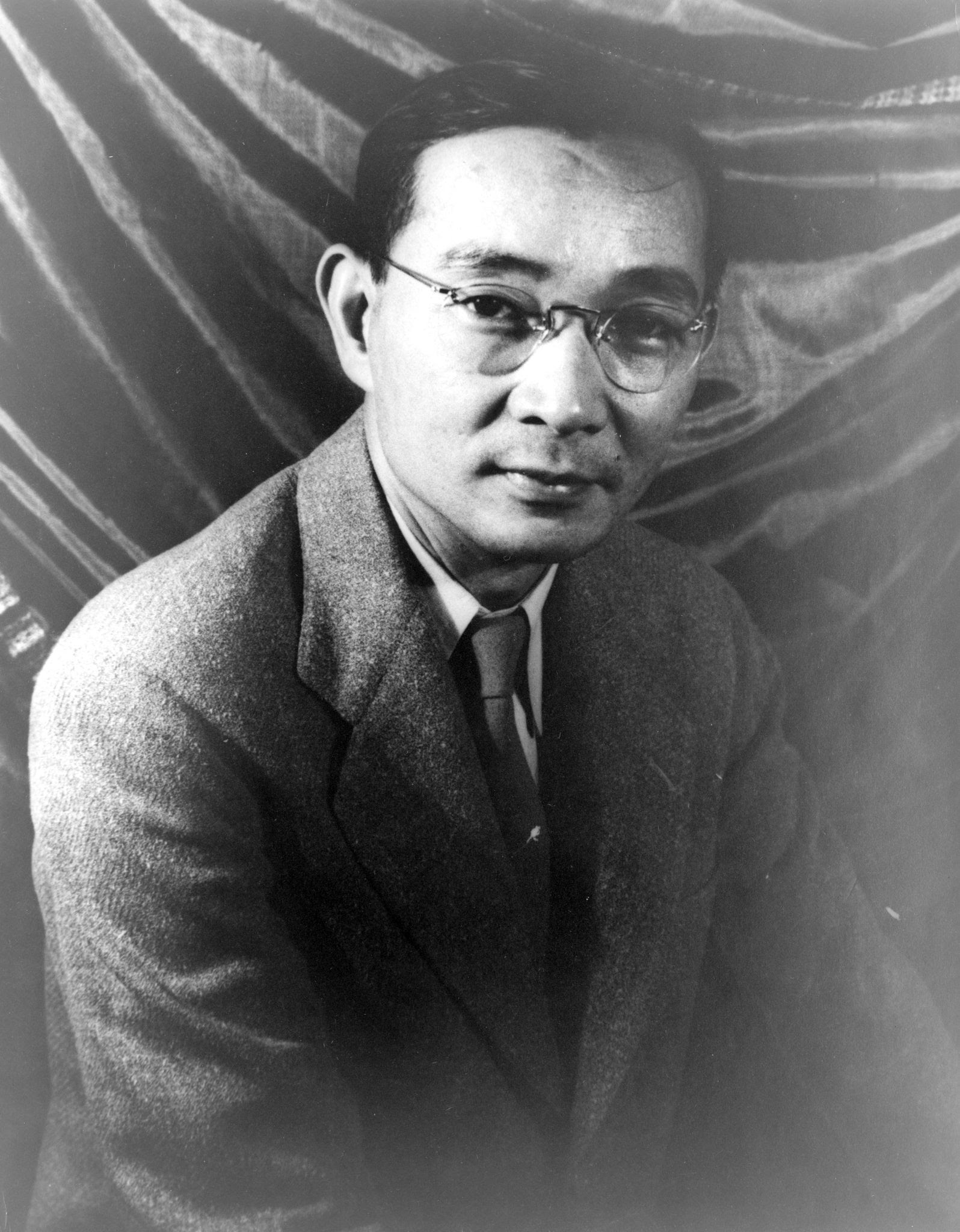

About the author:

Lín Yǔtáng 林语堂 (1895-1976) was born in Zhangzhou, Fujian province. His father was a Chinese Christian minister and Lin himself moved from Christianity to Taoism and Buddhism and then back to Christianity in his later life as recorded in his book From Pagan to Christian (1959). He studied at St. John’s University in Shanghai and then Harvard. He worked as a translator with the Chinese Labour Corps in France during World War One, and then moved to Germany to finish his Ph.D. (begun at Harvard) at the University of Leipzig. For several years in the 1920s he taught English literature at Peking University.

Lin embraced the New Culture Movement and was broadly supportive of the Nationalist government. He developed as a writer of witty and humorous feuilletons for a range of publications while also serving on the editorial board of many. In the 1930s he became distinctly more critical of the Nationalists and began publishing in America through an introduction to John Day Publishers from his friend, the author Pearl S. Buck. From the mid-1930s, Lin lived largely in the U.S., where My Country and My People was a bestseller. His other non-fiction books, as well as his novels, including Moment in Peking (1939) and A Leaf in the Storm (1940), also received praise.

Despite his witty prose, Lin became increasingly critical of Western racism and imperialism during the 1940s and, despite continuing reservations, was supportive of the Nationalist struggle against Japan. He later spent time trying to develop a Chinese typewriter, as well as living and working in Singapore, Hong Kong, and eventually in Taiwan, where he died. Lin Yutang was nominated for the Nobel Prize twice, in 1940 and 1950, but never received it. His wife, Lin Tsui Feng, was a cookbook author who did much to popularize Chinese cooking in America.

The book in 150 words:

Having established his reputation with foreign audiences as a thinker, philosopher, and interpreter of China to the outside world, My Country and My People was both an extension of this work and also cri de cœur, a passionate appeal, to support China’s ability to self-rule and to support her from the increasing aggression of Japan. However, above all the book is an enjoyable read — Lin shares with his readers his personal philosophy, his approach to life, the animal aspects, the human side, the importance of loafing, the home and family, enjoyment of life, of nature, of travel, of leisure, of culture, and the relationship to God. All done in his, by 1939, trademark style of anecdotes, tall tales, interpretations of Chinese legends and stories and humor, essentially turning the popular inter-war style of the feuilleton (light and witty articles though often with a critical point) into a book.

Your free takeaways:

Take off from the people the incubus of privilege and corruption and the people of China will take care of themselves. The people do not have to be trained for democracy, they will fall into it.

If the thing called “government” can leave the Chinese people alone, they are willing to let the “government” alone. Give the people ten years of anarchy, when the word “government” will never be heard, and they will live peacefully together, they will prosper, they will cultivate deserts and turn them into orchards, they will make wares and sell them, and they will open up the treasures of the earth upon their own initiative. And they will have saved enough to provide against all temporary floods and famines.

China is all ready now for democracy and government by law. The only obstacle is the present government by Face, Fate and Favor.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Lin Yutang was one of the most erudite and engaging of Chinese writers to appeal to Western readers and try to interpret his country to an overseas audience between the wars. He was perhaps not the first to experiment with this light and anecdotal style of observations of Western life and interpretations of Chinese society. A Qing diplomat, politician, lawyer, and ardent advocate of vegetarianism, Wǔ Tíngfāng 伍廷芳, had penned America, Through the Spectacles of an Oriental Diplomat (1914) after his 1908-1909 stint as China’s ambassador to Washington, D.C. In the United Kingdom, the Jiangxi-born artist and poet Chiang Yee (蒋彝 Jiǎng Yí) was attempting something similar with his “Silent Traveller” series. But Lin was something perhaps slightly more forceful. Though using a light style of anecdote, bon mots, and tales, he was also forcefully communicating China’s plight in the mid-1930s, as the political situation with Japan worsened and Lin feared a more authoritarian Nationalist government.

The impact of his books (many of which were bestsellers, widely reviewed and discussed in book clubs), especially My People and My Country, is that Lin became the major Chinese personality in the West to create a culture of sympathy and support for Nationalist China on the eve of the all-out onslaught by Japan on the country and just as Europe was starting to experience internal conflicts (Spanish Civil War, French Popular Front, the rise of Hitlerism) too. He was an emissary, a voice from a distant land explaining that land and culture in terms a foreign audience could understand, and seeking points of contact and commonality, shared values, and characteristics, while pointing out the fundamental and intriguing differences as something to be explored rather than feared (in the wake of the Yellow Peril era). Lin was a most effective “soft power” tool for Nationalist China in the 1930s, and his engagement technique of calm explanation, and inviting curiosity, remains in stark contrast to the current vogue for “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy. Lin comes to us in My Country and My People from another time of engagement almost unimaginable.

Lin Yutang has long been a regular favorite writer for many authors engaged with China. Pearl S. Buck (The Good Earth, etc.) wrote an introduction to the American edition of My Country and My People. Evelyn Waugh was a fan of Lin’s erudition and humor. Waugh’s wartime satire Put Out More Flags (1942) takes its title from a quote by an unattributed sage noted in Lin’s 1937 book The Importance of Living (FYI: “A man getting drunk at a farewell party should strike a musical tone, in order to strengthen the spirit…and a drunk military man should order gallons and put out more flags in order to increase his military splendor”).

It seems that despite having slipped from the public consciousness somewhat Lin is still influential on Chinese writers with an avowedly international perspective. The Chinese writer and regular commentator on all manner of matters Chinese, Zhāng Lìjiā 张丽佳 (Socialism is Great!, Lotus) described Lin Yutang’s My Country and My People as a great inspiration to her, “as the first book written by a Chinese, in English, specifically to explain China to a western audience. I have aspired to be an interpreter of China, too.” Additionally, the translator of T.S. Eliot into Chinese and creator of the long-running and bestselling Shanghai-set Inspector Chen detective series (see book No. 7) has also cited Lin Yutang as a major influence and inspiration. “He’s so knowledgeable, and so readable too,” Qiú Xiǎolóng 裘小龙 said.

Perhaps the social and political scientists reading My Country and My People today will find that Lin Yutang is also instructive in that he shows an alternative to the still oft-repeated, and sadly still commonplace, opinion (often coming across as a trope) that China is too populous for democracy, too unruly, its people too uneducated, too selfish for elected representative multi-party government and institutions. While not suggesting this is a simple overnight process, Lin (and here it is important to remember he was not a fully paid-up member of the KMT at all times) still ardently believes democracy possible. He forcefully negates any notion that somehow the Chinese people are “not suited to it.” This argument is of course still often propagated from senior ranks in the Communist Party down to casual foreign observers and regularly used to justify authoritarian one-party rule. Whatever the system in place, Lin Yutang shows us that authoritarianism — whether by the Nationalists or the Communists — was never a universally agreed political inevitability.

Next time:

Our two interpreters of China to the world so far, Eileen Chang (Zhang Ailing) and Lin Yutang, represent a country that would be swept away in 1949. So we need to visit one more interpreter, widely read and popular, who gave international audiences an up-close and warts-and-all look at China on the cusp of the 21st century. He eschewed urbane cosmopolitanism for a quest to see what he perceived as the “real China.”

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.