Women on Xiaohongshu don’t want kids. They want this monkey plushie from IKEA.

A stuffed ape is currently the most popular toy in China. Those who make posts about it on social media are making jabs — self-aware and humorous — at the government's request for young adults to have more children.

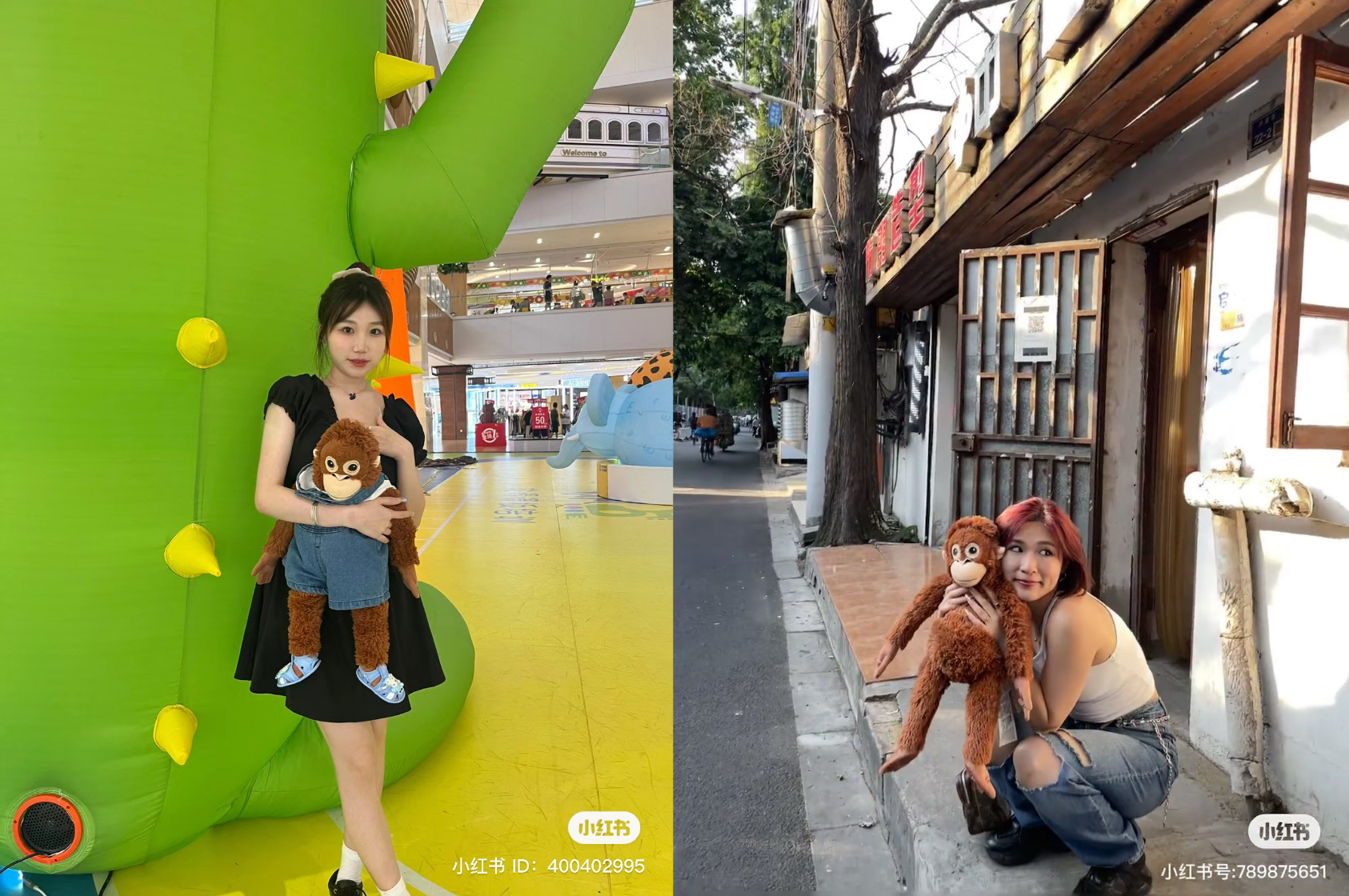

China’s birth rate is falling precipitously as young adults delay traditional life milestones like marriage and baby-making. But it turns out that parenthood is still appealing to them — just not in its traditional form. On Xiaohongshu, the preferred social media app of Chinese millennials and Gen Z, an obscure subculture surrounding a monkey plushie has gone from niche to mainstream in recent weeks, with owners of the toy playing mom and dad to the stuffed animal.

The subject of this online fandom is a cuddly orangutan sold by IKEA, the popular low-cost Swedish furniture retailer that currently has 37 stores across China. As part of IKEA’s soft toy collection called Djungelskog — meaning “jungle forest” in Swedish — the 26-inch, friendly-faced ape is categorized as a product for kids that can hang on one’s hip or back, “just like how real apes climb and hang in the rainforest trees,” according to IKEA’s website.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

But on Xiaohongshu, posts about the toy are mostly from adults. And just like how some parents are obsessed with putting their human babies online, owners of the plushie are incessantly sharing pictures of the lifeless object.

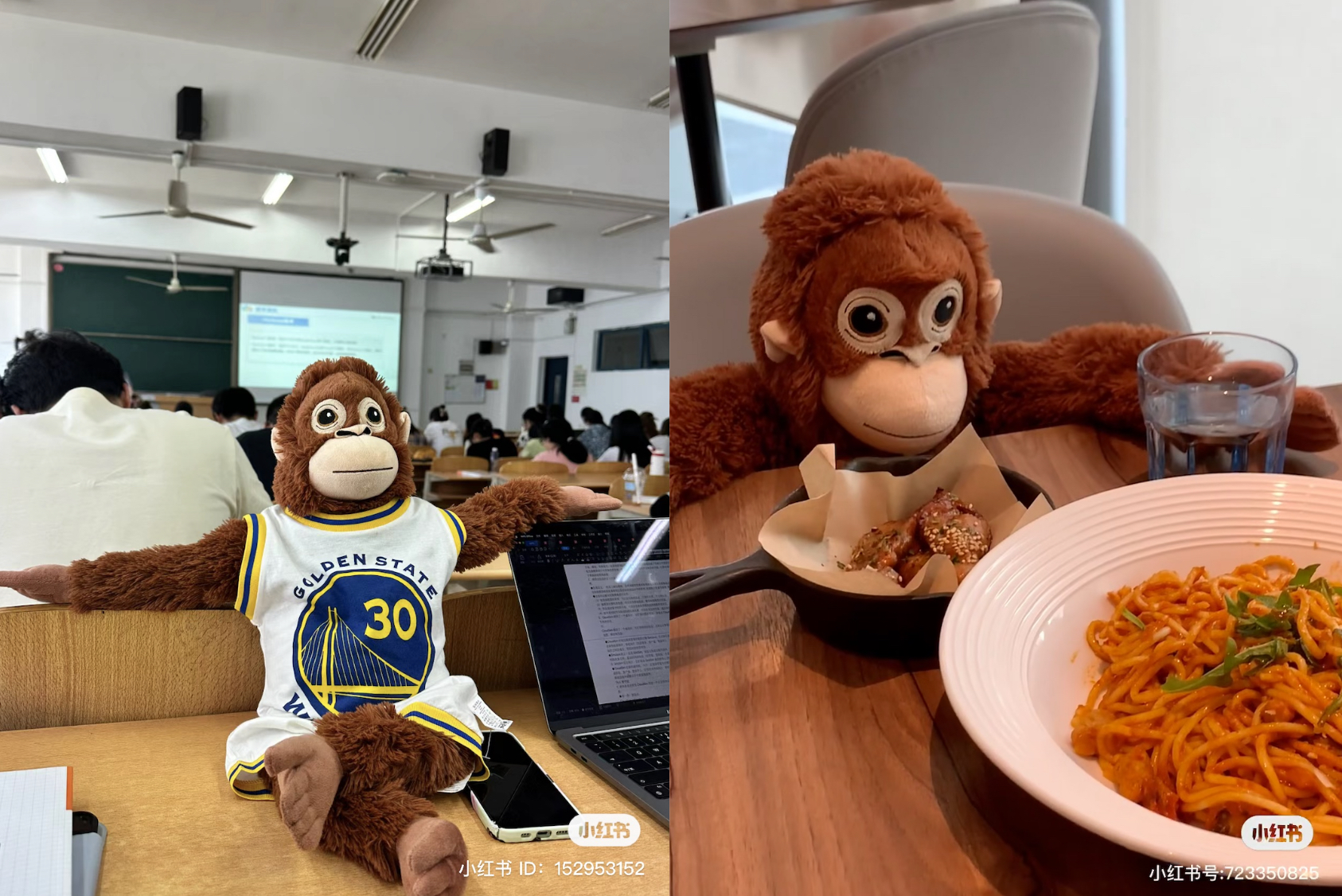

Under the hashtag “IKEA ape” (#宜家猩猩# Yíjiā Xīngxīng), which exploded in popularity this month and has garnered about 5.3 million views to date, many Xiaohongshu users put the monkey in various real-life situations, eagerly informing others in the community about “recent life updates” about their beloved “children.”

“I took my son to Pizza Hut today. I love him so much,” reads the caption of a photo showing the toy with a plate of pasta in front of him. Another creator shared a picture of the monkey sitting in the back of a car with a seat belt, writing, “We are stuck in traffic and this kid seems annoyed. I’m the one who’s hitting brakes constantly in the front so I don’t know why he thinks he has the right to be upset.” The monkey can be seen riding a train, checking himself out in the mirror, reading a book, watching TV, and taking a bath.

Many engaging with this subculture also appear to enjoy dressing up the monkey in children’s apparel. “I bought two new outfits for my son!!” a female Xiaohongshu user wrote while posting pictures of the monkey in an infant-size denim overall and a sweater romper. Other fashion-forward “parents” put their “baby monkeys” in carefully coordinated ensembles, with one toy donning a basketball jersey with a Nike headband and another wearing a McDonald’s-themed costume.

Such is the demand for the toy that it is beginning to become hard to find in IKEA stores. According to some Xiaohongshu users, the demand has resulted in a resale market with marked-up prices. Under a post of a reseller flaunting dozens of the monkey in an IKEA parking lot, angry fans flooded the comment section. “Now I know why it’s sold out everywhere!” one user fumed.

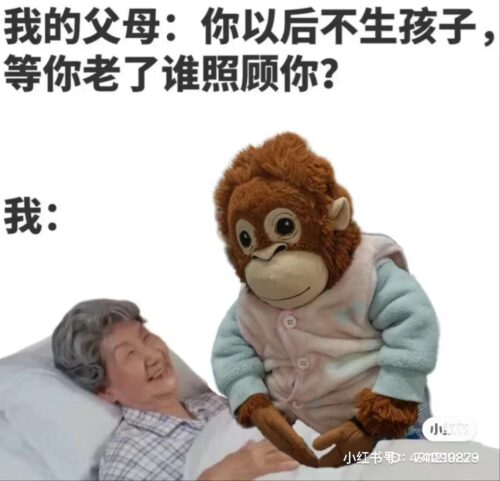

The monkey plushie blowing up on Xiaohongshu and being treated like a real human child is a surreal and timely peek at the mental state of many young adults in today’s China. Although Beijing has taken incremental steps in recent years to remove birth restrictions for married couples in an effort to encourage child rearing, China’s birth rates have been in a steady decline for the last five years. In 2022, China experienced its first drop in population in almost 60 years, and its birth rate also fell to a record low of 6.77 births per 1,000 people, down from 7.52 a year earlier and the lowest level since the founding of Communist China in 1949.

The high cost of raising children, along with pressure at work, unaffordable housing, and a generally pessimistic outlook on the future, has frequently been cited in surveys as the top factors preventing couples from wanting to start a family. Amid a growing trend of singlehood and childlessness among young professionals, many of them have chosen to raise cats or dogs, creating a thriving pet economy.

But now, as a hassle-adverse sentiment — spurred by the “lying flat” (躺平 tǎngpíng) and “let it rot” (摆烂 bǎilàn) movements that have taken root in China in the past few years — continues to dominate young people’s behavior, including their eating habits, many seem to think that taking care of a real pet is too much of a responsibility.

On Xiaohongshu, “parents” of the monkey plushie often praise it for being well-behaved, compliant, and an overall love bug that isn’t anxiety-inducing and is always ready to cuddle. Although humanizing a stuffed animal might seem bizarre, there’s an acute sense of self-awareness and humor in these posts.

It’s possible this post best exemplifies that. The words read:

My parents: If you’re childless in the future, who’s going to take care of you when you’re old?

Me: