This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

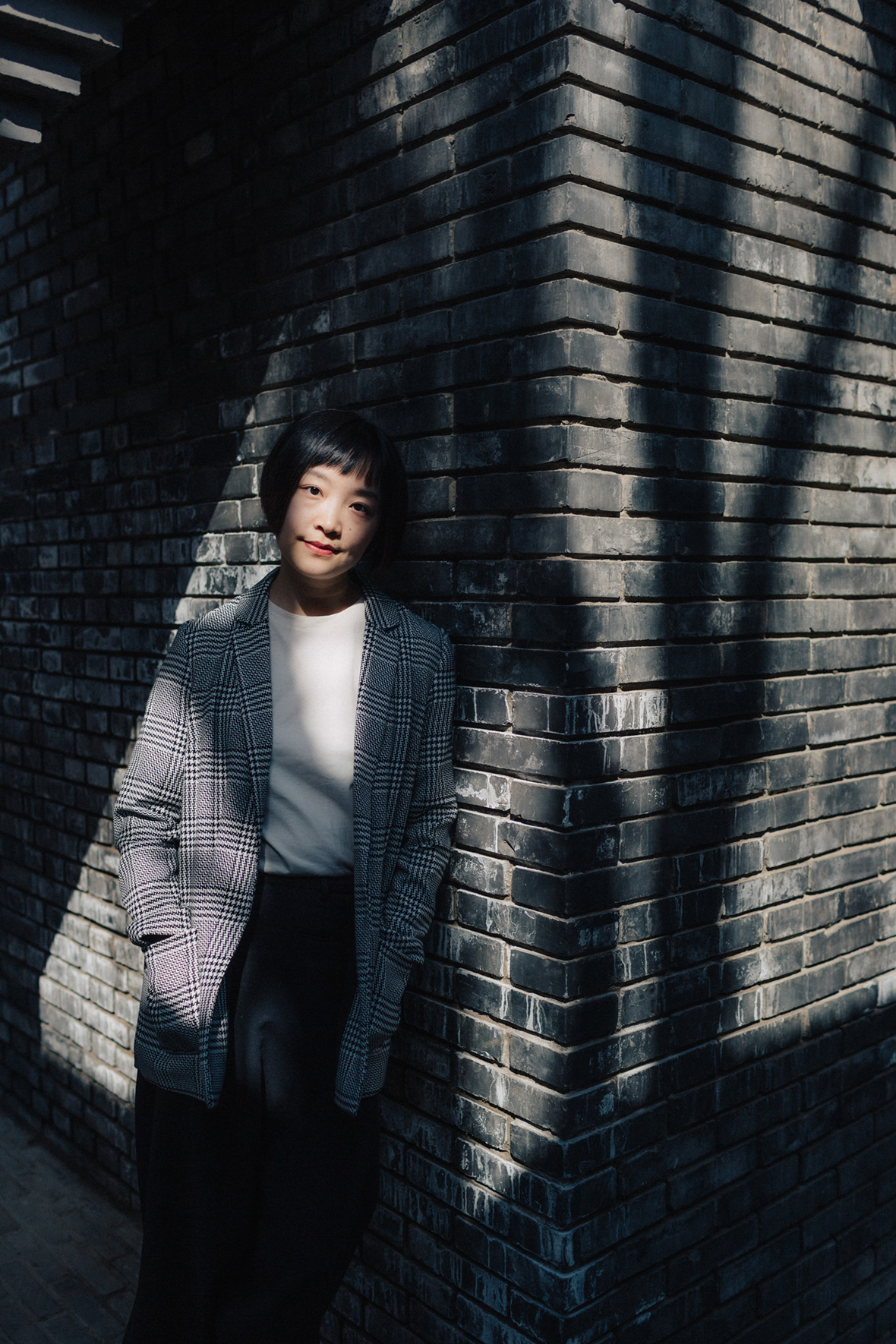

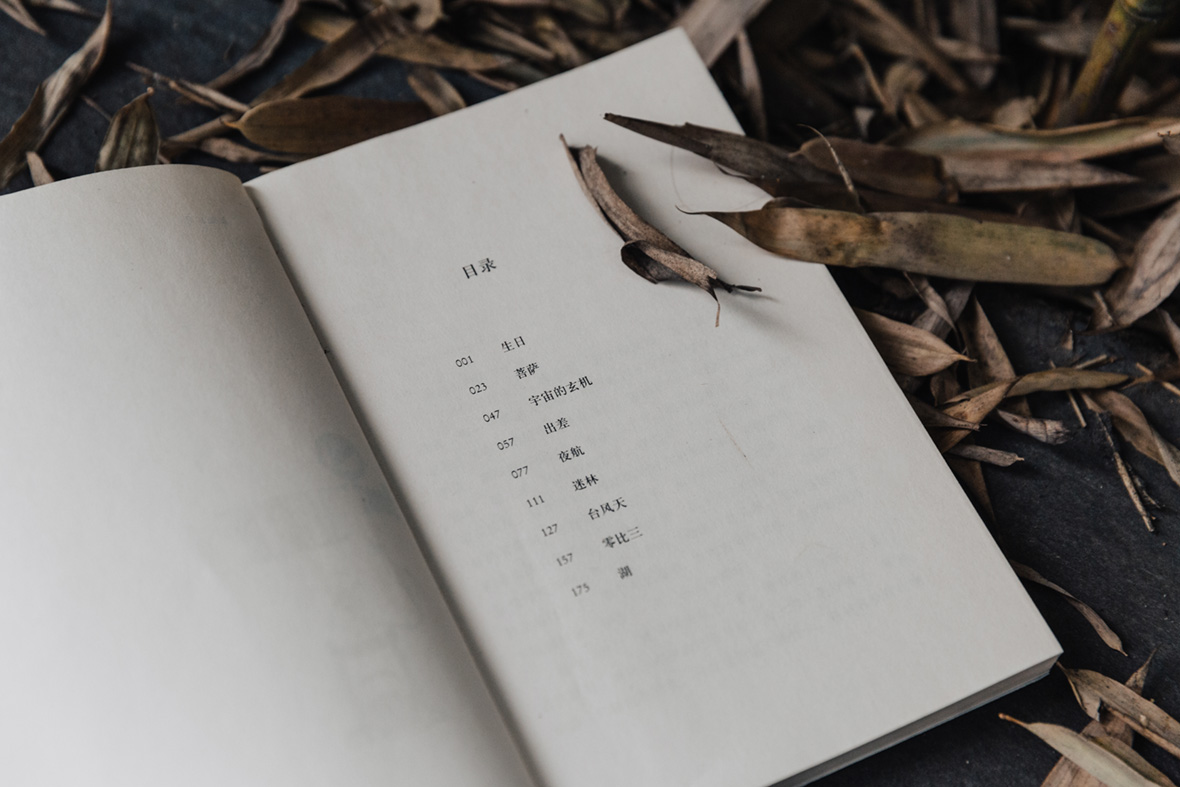

What’s a typhoon day? For Chinese author Lù Yīnyīn 陆茵茵, it’s an unforeseen disruption, a plan that comes to naught, a wound that you conceal, and a blow you can’t avoid. Typhoon Days, a collection of stories by Lu, presents nine women in their twenties and thirties living ordinary, if turbulent, lives. Some of these, like miniature biographies, span several years, while others tell the events of just a few days. Each short sketch brings the characters so vividly to life that you almost sense them standing there before you.

Lu doesn’t seem to control her characters from on high, all-knowing and all-powerful. Instead, she faithfully records their embarrassments, their pain, and their helplessness, piercing their fantasies and throwing open a window to let in the bracing air.

The stories all begin very quickly, plunging readers into the characters’ inner worlds. Small moments unfurl into profound narratives around life’s multifaceted nature. It reads like a friend’s blog, free of pretension or artifice. Readers are given complete transparency.

There’s nothing extraordinary in Typhoon Days, in that the writing is grounded in reality. The stories are of a humbler sort: the lonely single life of an overweight girl taking care of her father; a young woman with doubts about her married lover; a former couple whose hiking plans are interrupted by a typhoon; a working girl who’s too busy to examine her feelings. A brief description suffices because Lu’s stories don’t involve any earth-shattering events. Yet experiences like these make up everyday life for her young protagonists, who focus most of their waking mental energy on making sense of it all. How to deal with these events, how to accept them or extend or put a stop to them are the questions they face; ultimately, they’re struggling against their own obsessions and imagination.

The way these protagonists mutter to themselves will strike a chord with those who tend to get stuck in their head.

About marriage:

It was the first time she’d ever seen someone that age still unmarried. Everyone around her was married, no one lived alone. The man sat back down for a while, then got up and left. She watched him walk out the door, a shiny grease stain on each elbow. She felt as though a line of defense had been broken: there really were people who never found a spouse.

About a complicated relationship:

As he drove, she chattered on about this and that. Sitting next to him, she remembered the time he picked her up from the airport and she said that she wanted some dark chocolate. He reached into his backpack, took out five pieces—different brands, different flavors—and handed them to her from the left, in that angle, in that posture.

About work:

She’d met the boss of the other company once at a meeting. His body, she noticed, existed in different states of time simultaneously: his hands were in the past, recording the suggestion raised a moment ago; his mouth was in the present; his eyes had already reached the future. She could sense that division, and tell that he was there but not here.

The most moving sections of the book come from the characters’ internal monologues, as they observe their own behavior with cruel, self-mocking clarity. That self-awareness is what lets them keep their footing even when they’re pulled into the whirlwind.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Lu’s stories usually don’t end with a climactic revelation but instead stop in the middle. Many things are like that: there’s a moment of understanding, of insight, of letting go. The effects linger, but even people weighed down by their thoughts and feelings still have to go on living.