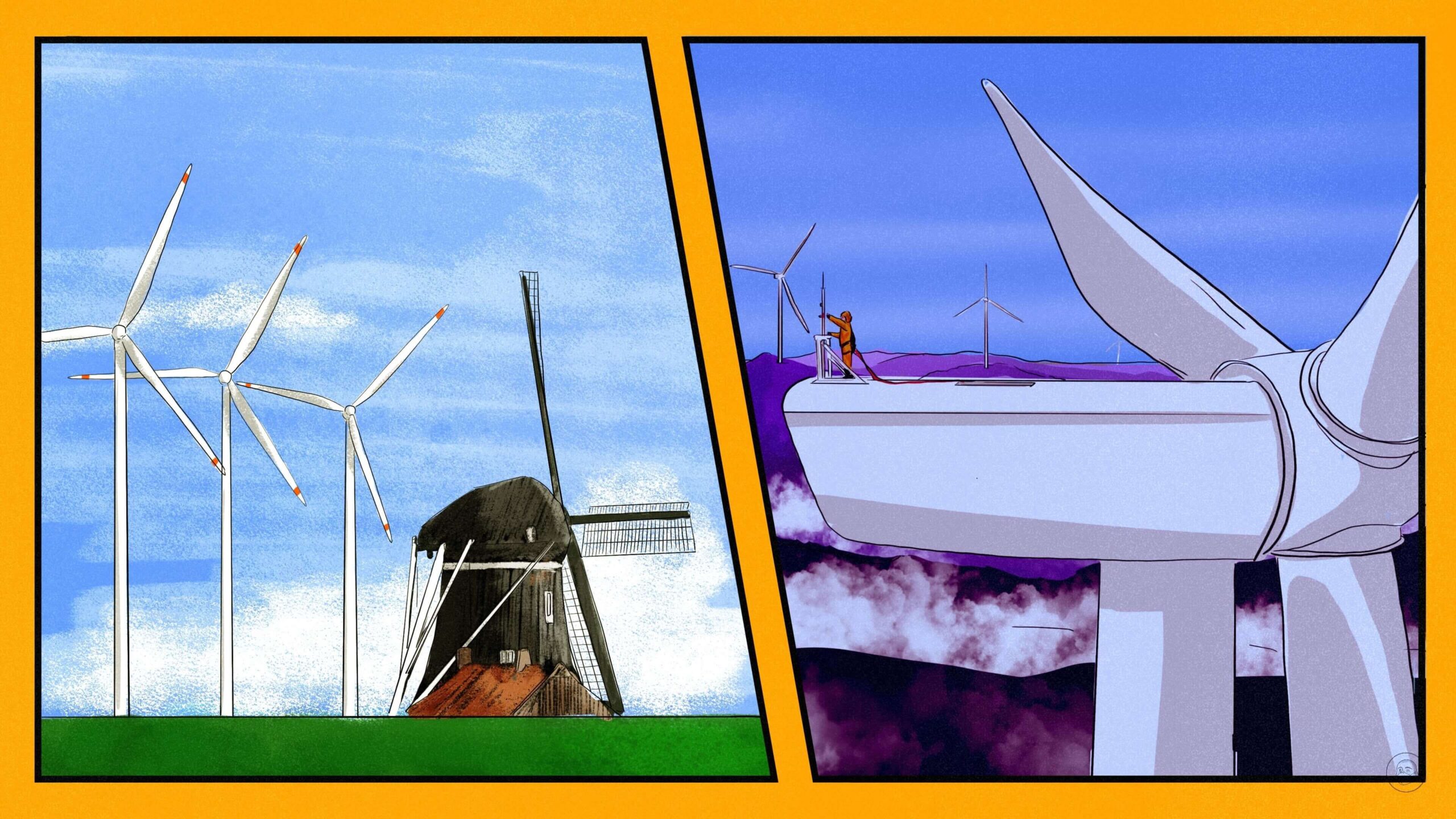

China’s wind power companies are giants, but they aren’t going to take over the world — yet

Chinese wind power companies are huge and so are their turbines, but they are struggling abroad because of import tariffs in Western countries and the sheer size of the gear and the cost of shipping it.

In 2022, a wind power turbine maker called Goldwind, little-known outside of China, installed 12.7 gigawatts (GW) to unseat Denmark’s Vestas as the world’s leading wind turbine supplier, becoming the first Chinese company to do so.

Founded in 1988 and headquartered in Beijing, Goldwind has led China’s booming wind turbine manufacturing sector for 12 years, and currently has a 23% share of the market in China, the country with the greatest installed wind power capacity in the world.

Five other Chinese companies were also in the annual top-10 list of the Global Wind Turbine Market Shares report by research agency Bloomberg NEF (BNEF).

While China is the world’s leading emitter of greenhouse gasses, and continues to permit the construction of new dirty coal plants, it is a world leader in adopting renewables. In June, the U.S. NGO Global Energy Monitor reported that as of the first quarter of 2023, China’s combined onshore and offshore wind capacity exceeded 310 GW. According to BNEF, China will install more than half of global wind power between 2023 and 2030. And it will double its renewable energy capacity generated by wind and solar to 1,200 GW by 2025, attaining goals set for 2030 five years early.

China’s booming wind industry manufacturers are hoping that 2023 will be the “big year of entering overseas markets” (出海大年 chūhǎi dànián) with bigger, cheaper turbines that foreign buyers cannot resist, especially as Western manufacturers are mired in bureaucracy and slowed by rising material and shipping costs.

A slow year

China’s wind rush began in 2003, with support from state subsidies, and peaked in 2021, when 48 GW of new wind capacity went online. But, in 2022, as central government subsidies for offshore wind projects were terminated, new installations in China dropped 21% to nearly 38 GW in the industry’s first decrease in installations in seven years.

While Goldwind and its Chinese peers on the top-10 list, including Envision (No. 4), Mingyang (No. 6), and Windey (No 7) compete with the likes of Vestas (the company that led Denmark’s grid to become 100% wind-powered), they must also compete with China’s reliance on fossil fuels: Coal imports nearly doubled in the first quarter of 2023 from the same period a year earlier, and Beijing has increased oil imports from Russia since it invaded Ukraine.

And despite the global demand for clean wind energy, in 2022, the top four Chinese wind power equipment manufacturers exported turbines whose capacity totalled a mere 2.29 GW.

Prospects in global markets

In the U.S., wind power is set for a significant expansion in 2023, boosted by a 100% production tax credit granted by the Inflation Reduction Act of August 2022. This surge in wind power could help the U.S. produce 80% of its energy from renewables by 2030, including 30 GW of new offshore wind power, meeting targets set by President Joseph Biden.

America needs a lot of new turbines and so does Europe. In the European Union, 16 GW of new wind infrastructure was installed in 2022, up 40% from 2021, but amounted to only about half the 31 GW that must be installed annually through 2030 if climate and energy targets set by the European Commission are to be met.

A protectionist focus could stop European and American companies and governments from purchasing wind power equipment and technology from China, but they will be hard-pressed to meet climate commitments without the involvement of Chinese companies.

Cheaper

Chinese wind turbines are generally up to 50% cheaper than those produced by their Western competitors.

Like their Western counterparts, slowed installations in 2022 saw three of the four top Chinese wind turbine manufacturers report drops in revenue but, unlike the Americans and Europeans, the Chinese firms maintained net profitability.

Goldwind, for example, reported net profit of 2.38 billion yuan ($331.39 million) in 2022 and 1.3 billion yuan ($181.01 million) in the first quarter of 2023. The Madrid-headquartered Siemens Gamesa, on the other hand, reported a 2022 loss of €940 million ($965 million) and cut 2,900 jobs in September. In Denmark, Vestas reported revenues down 369% on the year, cut 275 jobs, and reported a loss of €1.2 billion ($1.33 billion) in earnings before interest and tax.

In recent years, the global average price of wind turbines has hovered around $700,000 per megawatt, particularly in the Americas and Europe. In Asia, the average price per MW is around $400,000, “largely driven by raw material cost advantages that they have in China, and lower overhead and margin rates,” Philip Totaro, founder and CEO of IntelStor, a renewables market intelligence consultancy, told The China Project.

Bigger

Mingyang’s new 16 MW turbine is now the largest in the world. It was hoisted on July 18 off the coast of Guangdong Province in southern China. With a rotor diameter of 853 feet (260 meters), its blade covers an area roughly the size of ten American football fields, surpassing the rotor diameter of Goldwind’s largest turbine, standing in the South China Sea, by 26 feet (8 meters).

Mingyang says its large turbines are typhoon-proof and super efficient. The company’s Chief Technology Officer said in July that the larger they are, the more energy they can produce — if they can withstand rough weather. By comparison, Vestas’ largest is a 15 MW turbine at a test center in Denmark whose rotor reaches 774 feet, or 236 meters.

Tariffs and shipping costs

If Chinese manufacturers were allowed to enter Western markets, they would win on price every day of the week. But import duties have been imposed in the U.S. and Europe on Chinese wind turbines and their components that keep them pricey.

Western manufacturers want to protect their market share, and as Totaro puts it, “to do so they leverage their influence with the respective governments in Western countries to apply these import duties. They don’t want the Chinese to bring in the turnkey projects that they’re capable of executing with their equipment, their labor and know-how, and their finance.”

The size and weight of wind turbines, especially the giant ones, make them tough to ship around the globe — much tougher than, say, a Chinese-made electric vehicle or solar panel.

“Weight-to-value ratios and resultant transportation costs reduce the attractiveness of international wind trade,” Joseph Webster, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center, told The China Project. “In the United States, for instance, $20 billion was invested into the wind power sector in 2021, but imports were only $3.1 billion.”

As a result, Chinese turbine makers are fighting for scraps in Western markets and operating out on the margins. For example, in July, Windey shipped three onshore turbines from Hangzhou to Serbia, becoming the first Chinese company to install a wind project in that country, which, because it is not an EU member state, is not subject to import controls written in Brussels.

The Global South beckons

Chinese manufacturers seeking similarly low entry thresholds are actively pursuing sales of wind turbines in Africa, Eastern Europe, Central and South America, the Middle East, and Asia.

Chinese wind turbine manufacturers often are able to enter markets in Africa — and in countries such as Australia, Vietnam, Argentina, Brazil, and Pakistan — as partners of other Chinese companies developing infrastructure projects, including many Beijing-backed investment projects that are a part of the Belt and Road Initiative promoted by Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xí Jìnpíng 习近平.

“Chinese manufacturers are able to go [to these countries] with minimal to no import duties,” Totaro said. “They can take a turnkey solution into the market where they can propose a development project in concert with the local government.”

Chinese companies bring engineering expertise, equipment, and capital, he said. “The combination of all those things is where they have been able to see the most success.”

But not in the West, for now at least.

Companies:

- Vestas

- Siemens Gamesa

- Envision 远景能源

- Goldwind Science and Technology 金风科技

- Mingyang Smart Energy 明阳智能

- Windey 运达股份

Links and sources:

- China is building gigantic wind turbines, but are they too cheap? / The China Project

- China on course to hit wind and solar power target five years ahead of time / The Guardian

- China ramps up coal power despite carbon neutral pledges / The Guardian

- China’s Wind and Solar Are Now Almost Enough to Power Every Home / Bloomberg

- 国家能源局发布1-5月份全国电力工业统计数据 / China Electricity Council

- How China’s renewables boom is fuelling its coal expansion / Financial Review

- CWEA公布2022年中国风电吊装统计数据 / CWEA

- China’s installed solar and wind power capacity hits 31%, exceeding 800GW / Power Technology

- World Energy Investment 2023 / IEA

- Goldwind and Vestas in Photo Finish for Top Spot as Global Wind Power Additions Fall / BloombergNEF

- 金风科技胡江:能源运营,让千行百业实现降费节碳|谈碳 / 36Kr

- A massive 16 MW offshore wind turbine is now online in China / Electrek

- Wind energy in Europe 2022 Statistics and the outlook for 2023-2027 / Wind Europe

- EU calls on renewable industry to meet climate goals / En:former

- European Commission analysing higher 45% renewable energy target for 2030 / Reuters

- Infographic: U.S. Wind Power by the Numbers Q4 2022 / S&P Global

- FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Actions to Expand Offshore Wind Nationally and Harness More Reliable, Affordable Clean Energy / The White House

- Siemens Gamesa to cut 2,900 jobs as part of its turnaround / Reuters

- Vestas sinks to €1.2bn loss / Renews.biz

- GE Will Cut 20% of U.S. Onshore Wind Workforce / Powermag.com

- The world’s most powerful wind turbine has produced its first power / Electrek

- 明阳智能张启应:风机大型化让经济性更优 / In-en.com

- GE renewables earnings continue to slide / Renews.biz

- Factbox: What are the issues with Siemens Gamesa’s wind turbines? / Reuters

- 西门子跌倒, 中国风电企业吃饱? / 36Kr

- Europe’s Wind Industry Is Stumbling When It’s Needed Most / New York Times

- 大风机, 国产化, 出海趋势渐明 风电齿轮箱厂商寻机遇 / 21st Century Business Herald

- 2022 Annual Results / Goldwind

- China’s Wind Giants Hatch Plans to Muscle In on U.S., Europe / Bloomberg

- 3763万千瓦! 2022年风电并网装机数据公布! / China Wind News

- “风电老大”金风科技业绩下滑,董事长年薪降近四成 / Securities Times

- 海外大单频现,风电或迎史上最大交付旺季 / Wall Street CN

- China’s phantom menace in wind power / Wemake Consultores

- ‘China’s wind turbines are bigger than ever – but they’re no more financeable in the West’ / Recharge

- 运达股份让中国风机首次矗立塞尔维亚 / Eastmoney

- Why geopolitics will set the limits of China’s global wind power march / Recharge