This Week in China’s History: September 3, 1906

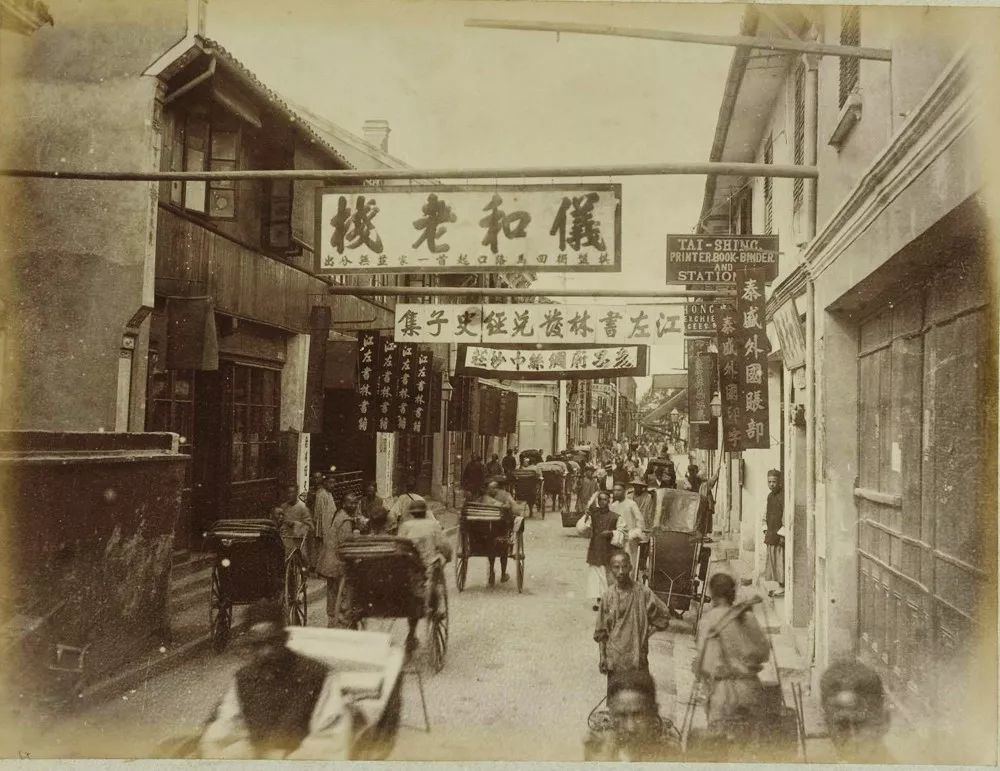

Fuzhou Lu is one of Shanghai’s most distinctive shopping streets. Harkening back to a time before online commerce was king, the street is the place to go to find books. Dozens of bookshops — some several stories tall — line the road, around the intersection with Henan Lu, along with (at least pre-COVID) portable bookstalls and pop-up shops.

For researchers — especially overseas scholars — without access to a major research library, in a time before reliable internet ordering, Fuzhou Lu could make or break a research project (or at least add, or subtract, years to it). It’s not hard to imagine, as historian Fei-hsien Wang put it, that “the unparalleled density of publishing houses and bookshops in [Shanghai] made it the ‘pivot of civilization in China.’”

“Pivot of civilization”: Wang was quoting a guidebook published 120 years ago, evidence that for well over a century, this neighborhood has been a center of learning and education. In the early 20th century, more than 300 presses and booksellers did business in the neighborhood, then known as Chessboard Street. And it was more than just a thriving community of bookstores. As Wang writes in his book Pirates and Publishers, Chessboard Street controlled the Chinese publishing industry; in many ways it was the Chinese publishing industry. The latest translations from Europe, America, and Japan reached the Chinese public only after passing through Chessboard Street. Fiction from home and abroad found eager readers via Chessboard Street.

Of course, the market for these books extended far beyond Shanghai. With such a high percentage of titles being published on Chessboard Street, the neighborhood was a tap that could control the flow of knowledge throughout China. That ability to control a market led to great potential for profits. And great potential for profits attracted attention from many who sought a piece of those profits.

In the last years of the Qing, as the dynasty enacted policies meant to pull it back from the brink of destruction, education was big business. New schools with new curricula sprang up across the empire, and those new schools needed books. Chessboard Street was the place to get them: Wang shows that more than 80% of the textbooks approved by the Qing ministry of education were published by just two presses on Chessboard Street — the Commercial Press and Civilization Books.

But although these two presses dominated the market in textbooks, that didn’t mean they were the only ones selling those books. Bookshops, of course, sold and resold books, sometimes at a discount. When discounts were deep enough, they raised suspicions about authenticity, and piracy was a problem. Small printing presses got copies of approved textbooks, reproduced them cheaply and quickly, and offered them at a discount relative to the legitimate books. As buyers came to Shanghai to place large orders — sometimes representing cities, counties, or entire provinces in need of teaching materials — piracy promised to be profitable. Very profitable.

With pirates, publishers, and customers all operating in a small area just a few blocks wide, Chessboard Street was the board for elaborate games of industrial espionage, ones that foreshadowed fights over intellectual property rights decades in the future. And that was why, on September 3, 1906, a team of private investigators fanned out across Chessboard Street to find out the truth behind a kidnapping.

The case they were looking into had begun — allegedly — on the afternoon of August 31, when one Lǐ Dífán 李迪凡 — a salesman for a small Shanghai bookseller — found himself in an opium den and approached by men claiming to represent a nearby province seeking textbooks. They arranged a follow-up meeting at a local teahouse, where Li brought samples of textbooks he had for sale, including several titles from the Commercial Press — Shanghai’s largest. Wang writes, “The provincial buyers were pleased by the quality of the books and the price Li offered. They signed a contract on the spot and arranged the delivery and payment for that afternoon” at a local hotel, where the two were staying during their business trip.

As Li made his way to the hotel with the books — down a blind alley with only one way out — he was surrounded and stopped by a group of men who dragged him into the headquarters of the Commercial Press, where the president of the company, Xià Ruìfāng 夏瑞芳, confiscated the books and accused Li and his partner of piracy.

Li managed to escape, without his books, and went straight to the police, where he recounted the story you’ve just read. Li accused Rui of kidnapping and theft. Sure, the books he was selling were Commercial Press titles, but they weren’t pirated: Offering popular textbooks at a discount was his business — it was how many booksellers made their living. To go further, he charged that the “bookbuyers” who had contracted with him were impostors, posing as provincial buyers to entrap Li.

To settle the case, the police turned to the city’s booksellers themselves. Compelled by their rapidly growing and profitable industry, Shanghai’s publishers enacted what would become China’s first copyright laws, encoded and enforced not by the Qing or the municipal government, but by two guilds, the Shanghai Booksellers Guild and the Shanghai Trade Booksellers Association.

The case left the guild with no easy option. Xia was one of the most powerful publishers in China, and a pillar of the publishing community. Yet Li represented the many small booksellers who made their living buying and selling on small margins and depended on the guild for protection. To wrongly accuse either jeopardized the entire enterprise.

Upon investigation, the Booksellers Guild uncovered yet a third story: This came from the provincial buyer — whom Li had accused of fraud — who claimed that the problem was not piracy but that Li Difan had cheated him by supplying books that did not match their order.

The guild delved deeper: This was what led them, on September 3, to dispatch six of their agents to investigate the episode. After a month of interviews, checking records, and tracking witnesses, what they uncovered was as mundane as it was convoluted: a case of mistaken identity; an overzealous employee; an anxious business owner; an unrecorded transaction. Wang captures the whole episode in his book. In the end, the guild “validated Li’s innocence [and] ruled that Commercial Press should not only compensate Li’s loss but also publicly apologize to him and the whole book trade for the disturbance they had negligently created.”

What are the lessons of Li Difan’s abduction? It is of course just one case in a complex web of piracy and copyright in late-Qing China. Wang charts the evolution of copyright — and its evasion — from the middle of the 19th to the middle of the 20th century, but its implications for the more recent past and even the present are manifold. “The social history of copyright in China…allows us to rethink the interplay of law, culture, and economic life, as the country undergoes profound sociopolitical changes and transitions.” Wang’s sentence refers to the change from empire to republic, but comparisons with the post-1978 reform era, or the present day, are invited. Then, as now, the enforcement of intellectual property rights is a complex mix of forces, including foreign pressure, local autonomy, quest for profits, and bargain hunting.

The self-policing regime of the booksellers’ guilds was full of abuses and inequities; it was also entirely homegrown. And it functioned better than any approach to the problem yet implemented, but it’s not clear that it was scalable, or that it could function at all in the world of the internet. It might just be, to paraphrase Churchill, that the booksellers’ guild was the worst of all copyright enforcement regimes, except for all the other ones that have been tried.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.