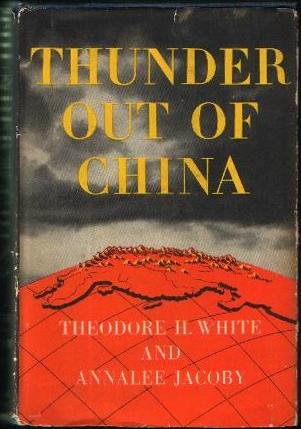

This is book No. 37 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“This provocative book, which has aroused a great deal of attention and comment pro and con, has the value of being straightforward and grounded on the authors’ own experience in China as members of the Chungking bureau of Time. It was not written in a judicial spirit, but in the angry tone of a crusader. In their review of recent Chinese history and in their suggestions for American Far Eastern policy, Mr. White and Mrs. Jacoby tread on many toes, personal and ideological.”

—Foreign Policy

“This is about Chiang Kai-shek, the failure of his experiment, and the corruption and complete unraveling of China under the pressures of Japanese occupation and war.”

—Orville Schell, Five Books

“An informed book which — while not pulling any punches nor concealing their weighed judgment — is at no time a biased, propaganda-laden thesis for one side or the other. A tremendously important book, at the vital moment.”

—Kirkus

About the authors:

Theodore H. White (1915–1986) was raised in an impoverished Jewish family in Boston. He consistently maintained that China was a mystery to him, despite being fluent in Mandarin and having a degree in Chinese history from Harvard. After college, he freelanced for the Boston Globe and the Manchester Guardian. Like many before him, he arrived in Shanghai to meet J. B. Powell, who referred him to Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) press office’s Hollington “Holly” Tong, who gave him a job with the Chinese Ministry of Information crafting press releases to distribute to the press corps. In 1946, he resigned in a dispute with Time and Life owner Henry Luce over the publication’s China coverage.

Annalee Whitmore Fadiman (1916–2002) was born in Price, Utah, and graduated from Stanford University. She headed to Hollywood and wrote several treatments and scripts for MGM, though eventually considered the movie business too silly to work in. She became a publicity manager for China United Relief and wrote speeches for Madame Chiang Kai-shek (Soong Mei-ling [宋美齡 Sòng Měilíng]). Heading to Asia, she married the correspondent Melville Jacoby, spent time in the Philippines, then escaped to Australia (where Jacoby died tragically on a tarmac). She was then posted to Chongqing. After the war, Fadiman wrote, lectured, and participated in the radio quiz show Information Please.

The book in 150 words:

White and Jacoby were joint members of the Chongqing Bureau for Time and Life magazines at the time when the city was the remote wartime capital of Free China. The book was one of the first war memoirs of China/Asia to appear, and was a runaway bestseller — selling more than a half-million copies — going into many repeated printings. The book is an evocative memoir of life in Chongqing in the war — the bombing, the relocations, the political schisms in the Chinese government, the involvement of the Americans and British in the city. The authors also analyze the factors that contributed to the end of the war and onset of the Chinese civil war — the Kuomintang, the Communist Party, and the American-sponsored Hurley and Marshall missions.

Your free takeaways:

In China half the people die before they reach the age of thirty. Everywhere in Asia life is infused with a few terrible certainties – hunger, indignity, and violence. In war and peace, in famine and glut, a dead human body is a common sight on open highway or city street. In Shanghai collecting the lifeless bodies of child laborers at factory gates in the morning is a routine affair.

The story of the China war is the story of the tragedy of Chiang Kai-shek, a man who misunderstood the war as badly as the Japanese or the Allied technicians of victory. Chiang could not understand the revolution whose creature he was as something fearful and terrible that had to be crushed.

Chungking, China’s wartime capital, is marked on no man’s map. The place labeled Chungking is a sleepy town perched on a cliff that rises through the mists above the Yangtze River to the sky; so long as the waters of the Yangtze flow down to the Pacific, that river town will remain.

The bombings were what made Chungking great and fused all the jagged groups of men and women into a single community. Chungking was a defenseless city. Its anti-aircraft guns were almost useless; the rifling of their old barrels had worn smooth by the time the Japanese began their major assault on the city.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

It is perhaps quite amazing to consider that Theodore H. White and Annalee Jacoby were barely 25 when they arrived in Chongqing, with Jacoby having just lost her husband in a plane crash.

Jacoby and White’s book is a superb memoir of China’s wartime capital, but it is also a cri de cœur for the Chinese “Third Way.” We now tend to see the end of the war, the Japanese surrender, and the resultant Chinese civil war as a binary choice between Nationalists and Communists. But it wasn’t quite so Manichean then. As Jacoby and White write at the end of Thunder Out of China:

Between the extreme right of the KMT and the disciplined Chinese Communists on the left stands a mass that seeks a middle way. It includes KMT moderates, the intellectuals, and non-partisan liberals, the splinter groups of the Democratic League. A huge proportion of the KMT rank and file belong to this group, as do most thinking people in China. This middle group, whose members are the sincerest friends of America, is surest of being wiped out in civil war.

Teddy White and Annalee Jacoby ultimately produced the most widely read indictment of American China policy in World War II. Their scathing commentary on Luce’s overt and misguided flattery of Chiang — which obviously did little to endear them to the Generalissimo — infuriated Luce (their boss), who pulled out the stops to try to suppress the book. However, Thunder Out of China made waves in America. Starting from the brief moment of patriotic glory after the Nationalist retreat to Chongqing, the book then covered the period when disillusionment and corruption set in and a “credibility vacuum” was created that allowed the Communists to gain ground.

The book led to a rift between White and Luce, who was an extreme anti-communist. Since the book has come out, most discussion has focused on White’s politics — too soft on communism, not really understanding Chiang? This has meant that Jacoby is often relegated to a secondary position as a writer, even though large portions are based on her reporting.

Next time:

Jacoby and White watched the war in China from the wartime capital of Chongqing as part of the sizable foreign press corps there. One Chinese reporter moved between Europe and China during World War II (or at least the parts of China that were accessible) and described for Chinese readers the global conflict raging from the London Blitz, the D-Day Landing, and the Burma Road supplies route.