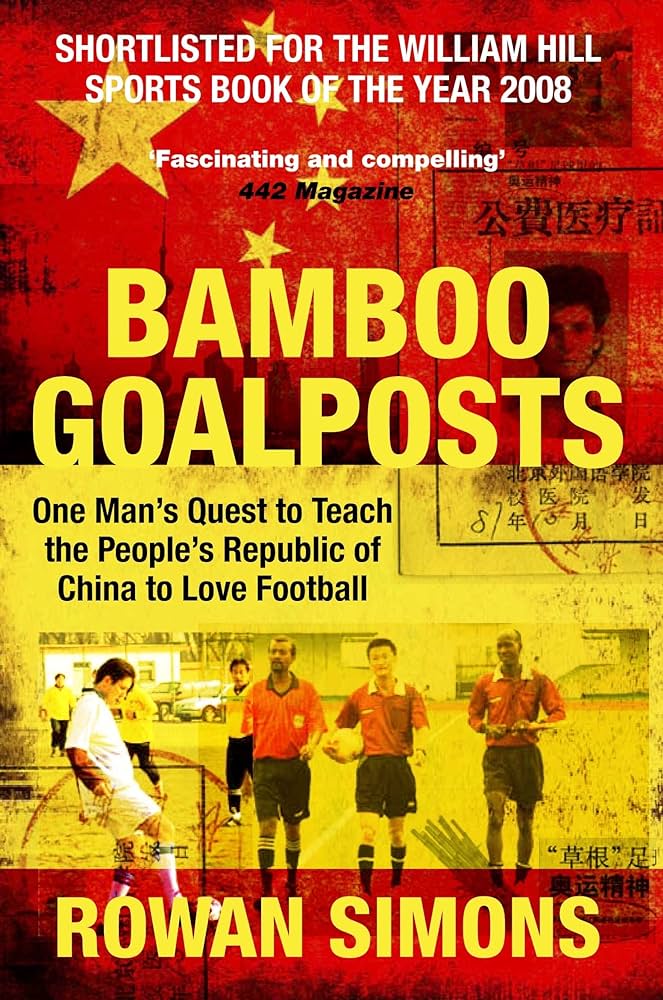

This is book No. 40 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“Bamboo Goalposts is a personal odyssey inspired by the selfless pioneers of amateur football who took the game around the world in centuries past, but somehow missed China.”

—Goodreads

“Deserves to be bracketed with some of the very best books about global football. Simons’ fascinating insights — he reveals how Chairman Mao used football in the 1950s to forge better relations with Eastern Europe, and that Deng Xiaoping invited Western outfits including New York Cosmos and West Brom in the late 1970s in order to convince the West he was committed to sweeping away the worst aspects of Mao’s crushing ‘cultural revolution’ — are mixed with first-hand accounts of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. Fascinating and compelling.”

—FourFourTwo Magazine

“His great passion in life is football, and in this often hilarious book he describes his attempts to convert the Chinese to the joys of the amateur game. Since the authorities have an elitist attitude towards sport and regard any gathering of more than ten people as politically subversive, it’s been an uphill struggle.”

—Mail on Sunday

“It manages to transcend its genre — the ‘isn’t football odd yet oddly similar to how it’s played elsewhere’ travelogue — by virtue of an idiosyncratic voice and a sharp eye for the absurd.”

—Observer

About the author:

Originally from England, Rowan Simons studied Chinese at Leeds University in the U.K. He started in the media industry in China in the 1980s and built a company — CMM-I — dedicated to his belief in soccer’s unique power to transcend all political, religious, social, and cultural barriers. In 2011, he was chosen to lead Guinness World Records into the China market, which has since become the biggest record-breaking market in the world. Additionally, Simons was the first person to bring the English Premier League to China (2009 Barclays Asia Trophy in Beijing) and was also a regular commentator on Beijing TV’s live broadcasts of English football in the 1990s.

The book in 150 words:

Rowan Simons became involved in soccer in China at multiple levels and intertwines these very different experiences in Bamboo Goalposts. Initially hired as a Chinese TV pundit on English and European soccer league games, he became well known across the nation’s millions of soccer-loving fans. Explaining the rivalries, tribal support, and histories of Europe’s clubs was fun. Covering the fortunes of the Chinese national team, less so. And so, Simons describes the constant and repeated disappointments for Chinese soccer fans. Finally, Simons invokes his own passion — a quest to develop a more comprehensive, government-supported grassroots football universe in China, one that could perhaps push through better players but would anyway boost health, fitness, and simply the enjoyment of playing soccer. The hurdles and obstacles were to be massive and often rather surprising.

Your free takeaways:

Not allowed to play football with the Chinese student body, my only option was to badger the small group of Chinese lads who also played on the college pitch once in a while. They were the off-spring of families who lived on campus but were not enrolled at the university. The first and only match I could get together was against their rag-bag group of which I often joined for a kick-around in the evenings, and I affectionately dubbed them Idle Sons FC for the occasion.

By the mid-1990s, tens of millions of people in China could provide you with a pretty good list of Europe’s major cities based on the names of the football clubs that play there. By contrast, the choice of “designated football cities” in China is based on political decisions. Just as China’s commercial TV industry is said to have launched in 1979 with a single ad placed on Shanghai TV, the symbolic birth of football sponsorship in China came in 1984, when Baiyunshan Pharmaceuticals was announced as the proud sponsor of the Guangzhou football team…

…but the Chinese headmasters who really needed to come on board often took a very different view. Firstly, they brilliantly argued that using their sports facilities would increase the cost of repairing them. Second, given the focus on academic achievement, they doubted that many parents would see optional after-school football lessons as a benefit. Third, in response to our ridiculous idea of opening the facilities and courses to all children, they said this was impossible from a “public safety” perspective. Finally, schools saw themselves as being in the special position of having fulfilled all their responsibilities to the wider community by being, er, schools.

When the Chinese Olympic team hosted a four-team invitational tournament in Shenyang a couple of weeks later, it lost its final match to North Korea by a single goal to nil, and the national football depression was complete. Again, there seemed to be no effort to reverse the score, and over half the crowd had left before the end. This time the commentators had no more to say and simply prayed the team’s problems could be sorted out before the Olympics began.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

China’s entire sports dilemma is the division between elite, medal-winning, glory-gaining sportsmen and women and the notion of sport-for-all, national fitness, sports as an egalitarian, dare we even say, “fun” pastime. And Rowan Simons’s book really deals with three separate but deeply intertwined issues: 1) the success of international soccer on TV with the Chinese public, 2) the fate of the seemingly eternally hapless national team, and 3) the tricky question of the grassroots development of the sport.

Simons has been at it — indeed, remains at it — trying to promote soccer at a grassroots level in China. His obstacles have included lack of decent pitches, obstinate school headmasters, intransigent cadres, academically obsessed parents, and lackluster sponsors. But his experiences in Bamboo Goalposts are revelatory of so much more about Chinese society and hierarchies. The well-known obsession with elite sports means parents see little in it for their kids to play sports; the government wants success and rates medals and trophies over mass participation. The official view of sports is that it’s for national glory: The benefits of exercise, recreation, and building teamwork and cooperation skills are all sidelined. And all the while, the continually dismal performance of the national team — most recently losing 1–0 to Syria last month — doesn’t exactly encourage hope.

Yet Simons has battled against it all, with proposal after proposal. And within that struggle are the small seeds of hope — the people he encounters who do get the positive aspects of sports, of teamwork, of exercise. Without doubt, Chinese TV viewers will go on watching Manchester United, Bayern Munich, FC Barcelona, and other super teams in super leagues, but encouraging a younger generation to just go out and kick a ball about appears to be as big a mountain to climb as ever.

Next time:

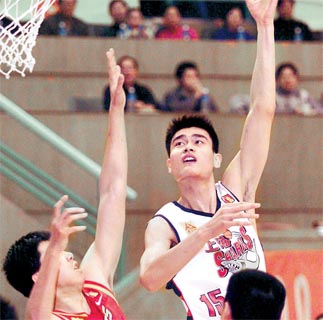

When it comes to soccer, China has a way to go in terms of players, teams, and leagues. But how about a sport China does seem to have perhaps performed a little better at — basketball? And that one very tall man who epitomized China’s ambitions for the game in the early 21st century.