This Week in China’s History: October 19, 1920

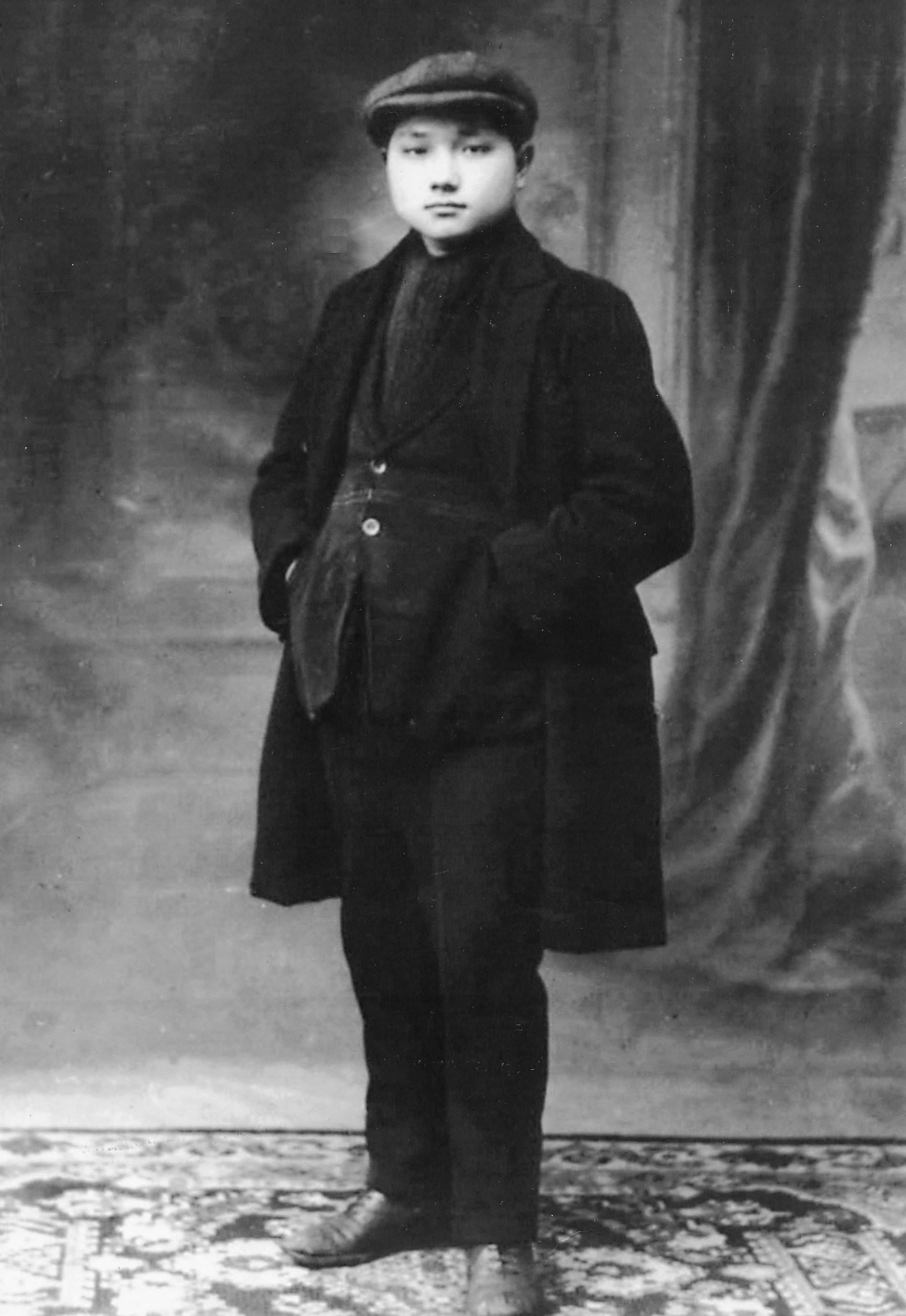

Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 arrived in the French port of Marseille on October 19, 1920, disembarking from the Lebon, a refitted cargo ship that had been enlisted in the service of the French government and the Chinese Labour Corps. The local press reported that the Chinese students, including the future leader of China and symbol of reform and opening, wore Western-style clothes, including a broad-brimmed hat and pointed shoes.

Deng had begun the trip as one of 84 students who set off down the Yangtze River from Sichuan Province. The late Ezra Vogel, in his biography of Deng, described Deng’s journey to France — via Chongqing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Singapore, and Sri Lanka — as “formative.”

Deng was just 16 years old when he set off for Europe, the youngest of the Sichuanese students. He was coming of age at a remarkable moment in China’s development as a nation. His hometown of Guang’an was not a major city, but it was well connected, a relatively easy boat-ride from Chongqing, which was itself less than a week’s travel from Shanghai. Major national events, like the May Fourth Movement, brought the youth of Guang’an into the streets, Deng included. His growing political consciousness took him to Chongqing, where he took part in still more nationalist protests. As Vogel put it, “the birth of Deng Xiaoping’s personal awareness of the broader world coincided precisely with the birth of national awareness among educated youth.”

The national awareness Vogel referred to was wrapped up in both love and loathing. The students were motivated by patriotism but also anger at how China’s government had been unable to protect or advance its interests. In this view, any chance for China to strengthen or advance required modernizing its politics, culture, and society.

Politically, these movements had aimed to move China away from the imperial structure of government and toward a more “modern” form of government. The goal seemed finally to have been accomplished when the revolution of 1911 replaced monarchy with republic. Many of the reformers and revolutionaries who had sought revolution were not only fiercely nationalist, they were socially and culturally progressive, and looked unabashedly at Europe as a model. The modern values of Europe — democracy and industrialization among them — were a contrast to what they perceived to be the backwardness from which China was struggling to emerge. France, in particular, was a desirable destination: a cultural center and a global power.

This in part fueled the movement that eventually brought Deng and thousands of others to France. Even before the fall of the Qing, societies were created to support local youth to study and/or work abroad in France. As early as 1908, students from China — including Deng’s home province of Sichuan — were making their way to France. These programs continued through the revolution, some with philanthropic goals, sponsored by local businessmen, others with political motives, organized by anarchists (anarchism preceded Marxist socialism as a political force in China by several years).

The Great War — World War I — changed the nature of the movement. The fighting in France made studying abroad there an unlikely possibility, but the mobilization of millions of men for the war effort created demand for workers. Both France and Britain enacted work-study programs that would bring tens of thousands of Chinese men to Europe.

Deng Xiaoping arrived in France just after the war, enrolling in a Chongqing school to compete for a scholarship to pay for his passage. As Vogel put it, Deng was “never particularly skilled in foreign languages,” and was not among those chosen, but in the end it didn’t matter: his father paid to send him, and Deng joined the cohort that arrived in France in the fall of 1920.

After landing at Marseille, the Chinese students were taken by bus to Paris, and then distributed to schools across the region: Deng wound up in Bayeux, in Normandy, where he expected to spend the next few years studying French and other subjects, while gaining work experience at the same time.

The journey did not go as expected, however. The culture shock of moving from inland China to France would be jarring under any circumstances, let alone during post-war reconstruction. Racism and xenophobia was widespread. Labor was in desperate need during the war, but less so when Deng and his compatriots arrived. French soldiers were returning to civilian lives, and there was no longer a labor shortage. Inflation was also high.

Amid all of this, the Sichuanese foundation that was sponsoring the passage to France was short of funds. In January, the Bayeux school was informed that its subsidy for the Chinese students would be ending. In March, Deng left Bayeux and began working in the town of Le Creusot, in France’s most important ordnance factory. Conditions were harsh, and Deng remained amid the blast furnaces for just three weeks before leaving and making his way to Paris.

At this point, the story takes an ironic, if predictable, turn. For decades, many Chinese progressives had looked to the West for political inspiration, France in particular. But the France of the 1920s was turbulent. Several Chinese leaders organized protests against working conditions and racism, and were deported for their troubles. Amid racial turmoil, economic difficulty, and just a few years removed from the Russian Revolution, the Chinese students did indeed find political inspiration, though not of the sort that their bourgeois sponsors anticipated.

Deng bounced between jobs and schools — working in a paper flower factory, then a rubber factory, in between attempts to enroll in trade and technical schools. Frustrated, and motivated, by his experience, Deng turned to radical politics. In the summer of 1923 — just a year after the Chinese Communist Party had been founded in Shanghai — he joined the European communist movement, working in a print shop under the direction of Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来, that produced a radical magazine aimed at promoting Marxism among overseas Chinese in France. The journal, which would take the name Red Light (赤光 chì guāng), catapulted Deng into prominence (among a small circle of Chinese communists).

As Vogel summarized it, “Having proved himself in the office, Deng was brought onto the executive committee of the Chinese Communist Youth League in Europe. At their meeting in July 1924, in accordance with a decision by the Chinese Communist Party, all of the members of this executive committee, including Deng, automatically became members of the Chinese Communist Party. At the time, the entire Chinese Communist Party, in China and France together, had fewer than a thousand members and Deng was not yet twenty years old.”

Deng Xiaoping remained in France until the summer of 1926. Tellingly, when he left, his destination was not immediately China, but the Soviet Union. He enrolled at Sun Yat-sen University in Moscow, where he embarked on formal study of Marxism and Leninism. When he returned to China, in 1927, it was the end of seven years abroad — but his journey had just begun.

This week’s column has relied heavily on the work of Professor Ezra Vogel, who passed away in 2020. I knew him for only a few years, and although he was already in his 80s, I can say that he inspired — perhaps intimidated — all who knew him with his seemingly boundless energy. Ezra was committed to fostering and improving greater understanding between China and the United States. I know he was pained by the deteriorating state of U.S.-China relations in the years before his passing, and his presence is missed all the more as we find ourselves in desperate need of knowledgeable and compassionate experts who could help us repair and rebuild a better relationship. RIP Ezra.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.