This Week in China’s History: October 30, 1852

Yale University’s main research library, Sterling, is meant to evoke a Gothic cathedral. The main entrance doors open onto a nave, lighted through stained-glass windows, with the circulation desk where the altar might otherwise be. Although the architecture resembles a church, the iconography is secular, including statuary throughout the library.

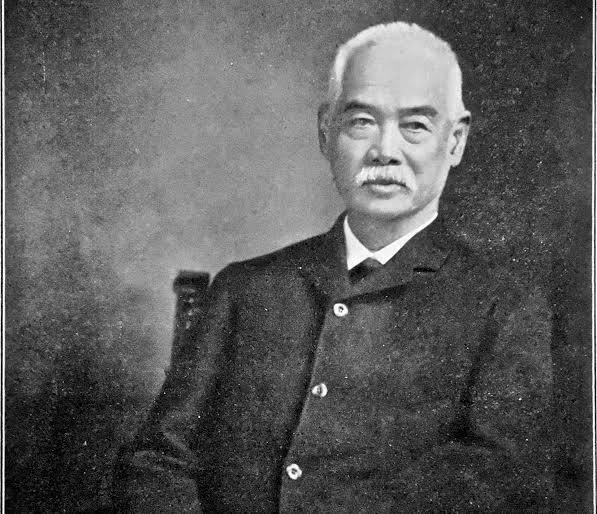

In one corridor is a lifesize statue of a Chinese scholar, Yung Wing (容闳 Róng Hóng). The sculpture — a gift from Yung’s hometown of Zhuhai — depicts Yung as a young man, in the 1850s, when he spent many hours in the halls of an earlier Yale library on his way to becoming the first Chinese to graduate from an American university. He was still a student at Yale — beginning his junior year — on October 30, 1852, when he took the oath that made him a naturalized U.S. citizen: part of a career that saw him become an instrumental figure in the history of U.S.-China relations.

Yung’s exposure to American education began even before he left China for New England. He was just seven years old when he began attending a missionary boarding school in Macao. That first school disbanded amid the Opium War, but Yung Wing then enrolled in a school taught by missionary Samuel Robbins Brown. Brown was a Yale graduate, and contrasted his own education — and American industry and expansion — with what he saw as a conservative and limiting Chinese system. Brown instilled in his students the notion that a Western education — an American education, and more specifically a Yale education — would shape a student’s character while providing practical tools for improving society. When Brown returned to the United States in 1847, he brought with him three of his top pupils, including Yung Wing. Yung enrolled in a Massachusetts boarding school, under the supervision of Brown’s mother, and then Yale.

As scholar Paul Harris observed in his article on Yung Wing’s time in America, “Yung had absorbed from Brown a misleading impression of American collegiate education.” Hungry for scientific insight and practical tools, Yung instead found a “curriculum still dominated by the classical liberal arts, stressing ancient languages and moral philosophy.” This was especially true of Yale, which “was slow in moving toward a curriculum that would offer practical training in scientific method and professional skills.”

It was just as Yung was graduating that the course of study he so desired was becoming possible. He wrote in his autobiography, “I wanted very much to stay a few years longer in order to take a scientific course…just as that department was coming into existence. Had I had the means to prosecute a practical profession, that might have helped to shorten and facilitate the way to the goal I had in view; but I was poor and my friends thought that a longer stay in this country might keep me here for good, and China would lose me altogether. The scientific course was accordingly abandoned.”

Yung Wing graduated from Yale in the spring of 1854, and returned to China, seeking a way to reform Chinese politics and society. He may not have gotten the practical education he sought, but he had, he believed, unparalleled connections and credentials. Notwithstanding JFK’s quip (on receiving an honorary Yale doctorate) that the best of both worlds was a Harvard education and a Yale degree, in Harris’s words, “Yung soon learned that no Chinese shared his view that a Yale degree conferred special status.” He struggled to find a position that was befitting his perceived status, and was left with a contradiction: His Chinese colleagues were unimpressed by his credentials (and he had been educated entirely in English), but racism undermined his status with Westerners.

Although he found commerce a disappointing career, beneath the education he had received, Yung Wing found success in China, first as a merchant, facilitating trade in tea between Taiping-held areas and treaty ports. His skill at navigating between Chinese and foreign actors gained the attention of Zēng Guófān 曾国藩, who was looking for ways to modernize China’s military and industry. Zeng sought machinery and technology from the United States, so finding an American citizen like Yung Wing at hand was an obvious opportunity Zeng took advantage of. Zeng hired Yung to his staff and then sent him to the U.S. to acquire machinery that would form the foundation of the Jiangnan Arsenal. (Arriving in the midst of the U.S. Civil War, Yung offered to enlist in the American army, as a citizen, but was denied.)

Returning to China, Yung Wing remained committed to promoting mutual ties and understanding between China and the United States. Seeking a way to expose more Chinese students to the education he found so valuable, Yung proposed the governor of Jiangsu to, in the words of historian Edward Rhoads, “in essence, to replicate his own experience on a grand scale.” The proposal that eventually was approved called for 120 Chinese boys — 30 per year for four years — to be sent to the U.S. for study, first in New England boarding schools and then on to universities. This Chinese Education Mission became a signature component of Qing self-strengthening.

Back in the States, Yung was honored by his alma mater in 1876 with an honorary Doctor of Laws degree, and laid the foundation for further U.S.-China understanding two years later, when he donated 1,200 volumes that would become the core of Yale’s East Asian library; Yale soon thereafter appointed the first professor of Chinese studies in the U.S. (Supposedly, Yale’s faculty declined to make the appointment until Yung made it clear that he would instead give his library to Harvard.)

This was in many ways the high point of Yung Wing’s career promoting ties between China and the United States.

The Chinese Educational Mission abruptly ended in the summer of 1881, by which time 43 students had attended or were currently enrolled in universities (about half of them at Yale, the rest spread across nine northeastern colleges, led by MIT and Rensselaer Polytechnic). If one of the program’s goals was creating and strengthening cross-cultural ties, it was shut down in part because of its perceived success. Cultural conservatives in China, who had always viewed the program suspiciously, raised alarms when the boys took up American habits like Western dress, dating American girls, and playing baseball. Of even greater concern, many of them began to practice Christianity. Alongside this, the mission was never able to achieve one of Yung Wing’s primary goals: admission to the United States Military Academy or Naval Academy. Without this, resisting the increasingly loud calls to bring the boys home became difficult.

And from the American side, forces of cultural conservatism and xenophobia were just as strong, or stronger, and growing. Anti-Chinese sentiments, and actions, were growing in the U.S. The Los Angeles Chinatown Massacre was one example, but outbreaks of violence and persecution of Chinese in America became widespread, leading to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

Yung Wing worked as a diplomat for the Qing empire, helping to negotiate the end of the 1895 Sino-Japanese War, but his politics soon made him persona non grata in China: After the Hundred Days’ Reform movement of 1898 was undone, the Qing government placed a price on his head.

And as for the citizenship that Yung Wing earned this week in 1852? Turns out it was not all Yung believed it to be. Persecuted by the country of his birth, Yung was likewise excluded from his adopted home, even though he had American citizenship, as well as an American family. When, in 1902, Yung applied to return home to the U.S. (for his son’s graduation from Yale, it seems almost unnecessary to add), he was refused, with authorities citing the Chinese Exclusion Act’s ban on immigration from China.

Yung eventually relied on friends and connections to sneak back into the U.S., and he was able to attend his son’s graduation. He lived the rest of his life in Hartford. When he died in 1912, the New York Times published his obituary, noting his graduation from Yale and describing it as “some years ago occup[ying] a prominent place in Chinese diplomatic circles.”

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.