The politics of passing on

In China, the death of a esteemed comrade is never strictly a private matter.

When Lux Nayaran, the co-founder of content analytics company Unmetric Inc, fed 2,000 New York Times obituaries into a natural language processing program, he found that most all the people featured, famous or not, had used their talents for good. They had, he said, “made a positive dent in the fabric of life.” Had Nayaran instead run 2,000 obituaries from Chinese Communist Party leaders through his program, he might have found something astonishing — that they had all made more or less identical dents in the stiff fabric of Chinese politics.

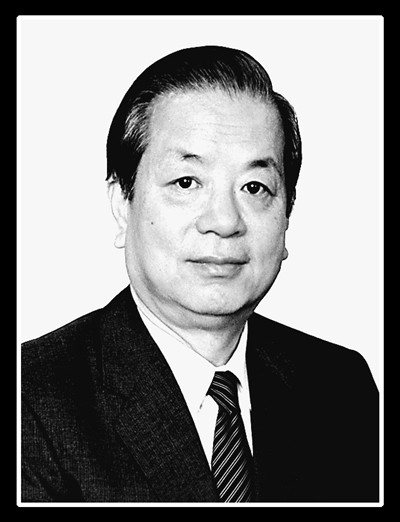

After the death last month of former Chinese foreign minister Qian Qichen (钱其琛), the official People’s Daily newspaper carried a terse synopsis of the man’s life, calling him an “excellent Party member,” a “time-tested fighter for the communist cause,” a “proletarian revolutionary,” and last but certainly not least (he was a diplomat, after all), an “outstanding leader on our country’s diplomatic front.”

But these superlatives were entirely run-of-the-mill. Qiao Shi (乔石), the former chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, had been similarly lionized after his death in June 2015, his official obituary calling him “an excellent member of Chinese Communist Party, a time-tested fighter for the communist cause, an outstanding proletarian revolutionary and politician, and an exceptional leader of the Party and the country.”

The January 2015 obituary of Yang Baibing (杨白冰), the People’s Liberation Army general who reportedly signed the order to fire on student demonstrators in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, had also extolled him as “an excellent Party member, a time-tested fighter for the communist cause, a proletarian revolutionary, and an outstanding leader of political work within our military.”

Even over death, the Chinese Communist Party has the final word. The death of any “comrade” is a deeply political matter, and its meaning must be ascertained through the deadening discourse of the Party.

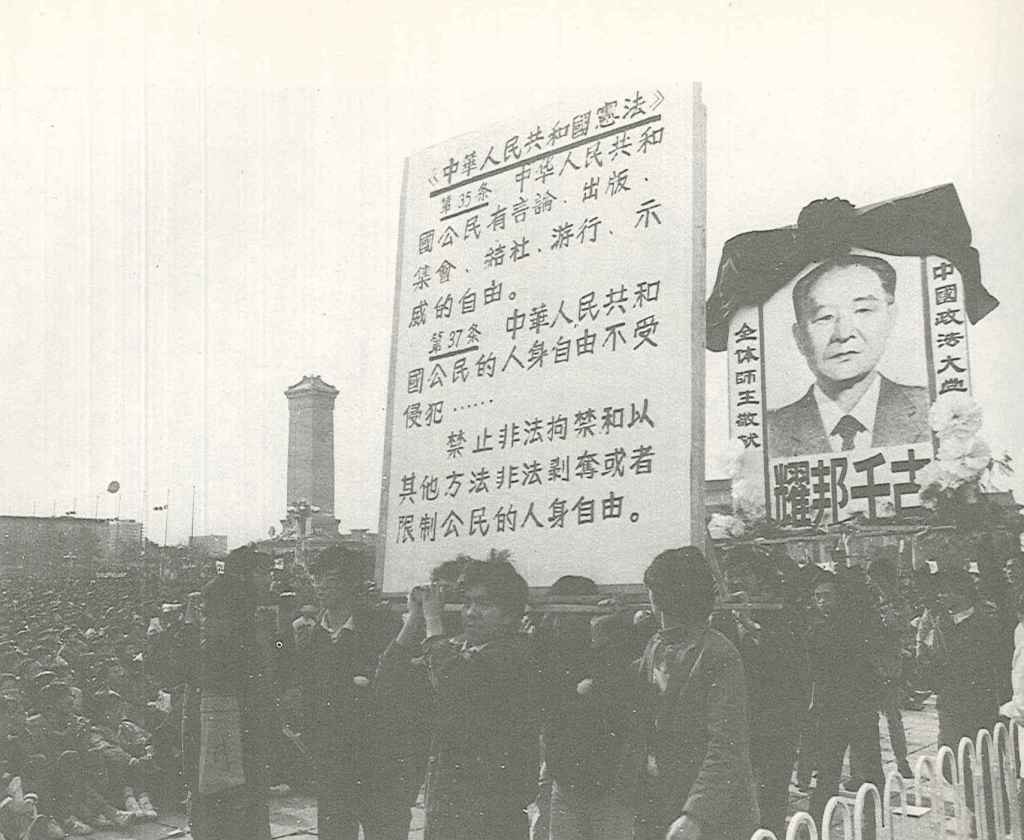

One important reason for this is of course that deaths can have an outsized impact on political life. Consider how the death of Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) on April 15, 1989, “fell like a spark into the highly flammable atmosphere of elite division and popular disaffection.” Or consider how the immediate possibility of the death of Jiang Zemin (江泽民), whose political influence is an unknown quantity, has impended over Chinese politics for almost a decade.

When the memorial service for Qian Qichen (钱其琛) was held on May 18, media in Hong Kong noted the conspicuous absence of Jiang, under whom Qian had served for more than a decade. Jiang had been placed, along with President Xi Jinping (习近平), on the official roster of mourners. Could his absence be a sign that he was edging closer to death? If so, what would this mean for Chinese politics in the run-up to this year’s 19th National Congress?

Jiang will turn 91 on August 17 this year. Or won’t he?

Deaths conjure up legacies, and legacies are a core matter of ideology and legitimacy for the Chinese Communist Party. Which means a lot is riding on the official obituary. “Well, then, is there any political logic in the obituary that follows the death of a leader?” a column at Sohu.com asked following Qian’s death on May 9. “The answer is: of course there is.”

In a column shortly after the death of Qiao Shi, the former NPC chairman, the “News Dig” section at Sina.com took a deep dive into the obituaries of 13 former members of the Politburo Standing Committee. Here is how “News Dig” characterized the practice of Party obituary writing generally:

The ruling party’s assessments of political figures who have passed away is not only about evaluating the person but is also an important political consideration made by the ruling party. The obituary is an extremely serious matter, and it can be said that every word is carefully weighed and has deep significance.

So who, then, is doing all of this careful weighing of deep significance? Well, that all depends.

The obituaries of Party and government leaders generally involve five major institutions — 1) the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, 2) the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 3) the State Council, 4) the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, and 5) the Central Military Commission (CMC). But the deaths of different political figures will touch on these institutions in different ways or combinations. In the case of Qiao Shi, institutions 1–4 were all jointly involved, according to “News Dig.” For Yang Baibing, institution 5, the CMC, was naturally crucial, given his status as “an outstanding leader of political work within our military.”

CLICK HERE for a regularly updated list of official Chinese Communist Party obituaries.

Xinhua News Agency was responsible for releasing the official obituaries in both of the above cases. But that isn’t always the way it works, either.

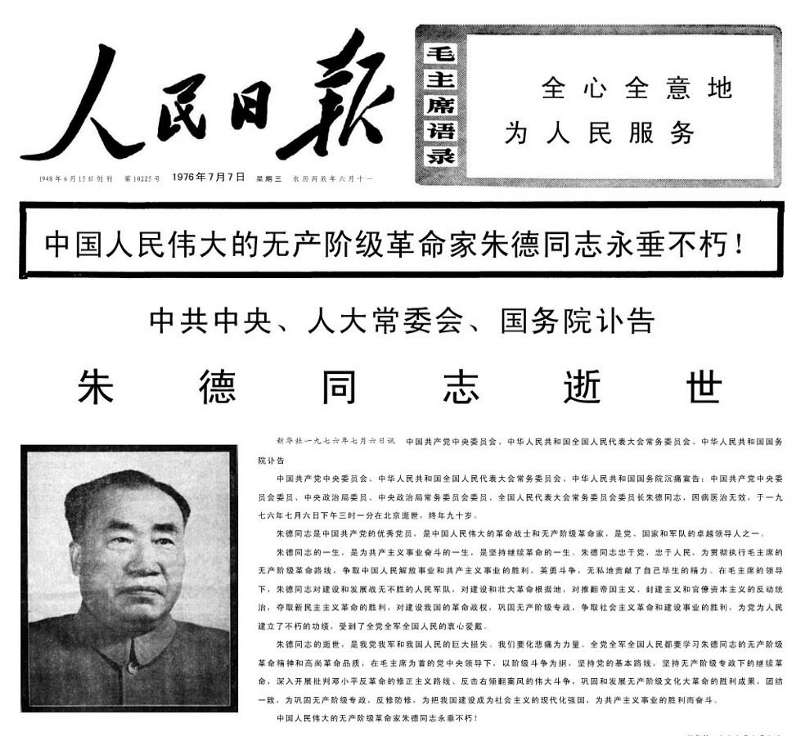

When reformer Hu Yaobang passed away in 1989, his obituary was released directly by the Central Committee. In other cases, as with the death of former premier Hua Guofeng (华国锋) in 2008, and PLA general Liu Huaqing (刘华清) in 2011, Xinhua can release official obituaries without the direct involvement of the above-mentioned institutions.

At the level of the text, what do the various cuoci (措辞), or turns of phrase, in these official obituaries mean? And who gets what?

As you might imagine, it’s all very complicated.

The titles “excellent Party member” and “fighter for the communist cause” can be applied quite generally to Party and government leaders. The descriptors “time-tested” or “devoted” are often placed before “fighter for the communist cause,” as was the case for the obituaries of Deng Xiaoping, Hu Yaobang, Chen Yun (陈云), and others.

The phrase “proletarian revolutionary” is generally applied with either “great” or “outstanding” up front. Given a choice, any leader worth his salt should prefer to be “great” over “outstanding” — because this places him in the company of Deng Xiaoping, Ye Jianying (叶剑英), Chen Yun, Yang Shangkun (杨尚昆), Hu Yaobang, Peng Zhen (彭真), and Deng Yingchao (邓颖超). Slightly lesser figures, like former vice premier Yao Yilin (姚依林), must settle for “outstanding.”

Hua Guofeng, the former CCP chairman drop-kicked into retirement by Deng Xiaoping, ended his life in relative political obscurity. For him, then, there was no superlative up front — he was just (poor Hua) a “proletarian revolutionary and politician,” plain and simple.

The terms “outstanding proletarian revolutionary” (杰出的无产阶级革命家) and “proletarian revolutionary” (无产阶级革命家) are generally used for state-level deputy officials (副国级官员), also sometimes called “sub-national” leaders (those in second-tier Party or government positions).

Leaders who were responsible for work related to the military are generally appended with such titles as “military expert” (军事家), “commander” (指挥员) and “political worker” (政治工作者).

Leaders’ obituaries may also, of course, make references to the areas in which they most clearly achieved. The official obituary for Peng Zhen, who had served as Secretary of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission in the 1980s, said that he was the “principal layer of the foundations of socialist rule of law in our country.”

After his death in 1997, Deng Xiaoping was called in his obituary “the chief architect of socialist reform and opening and the building of modernization,” and referred to as “the creator of the theory of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Obviously, it is a special distinction to be designated in such a way as a trailblazer nonpareil.

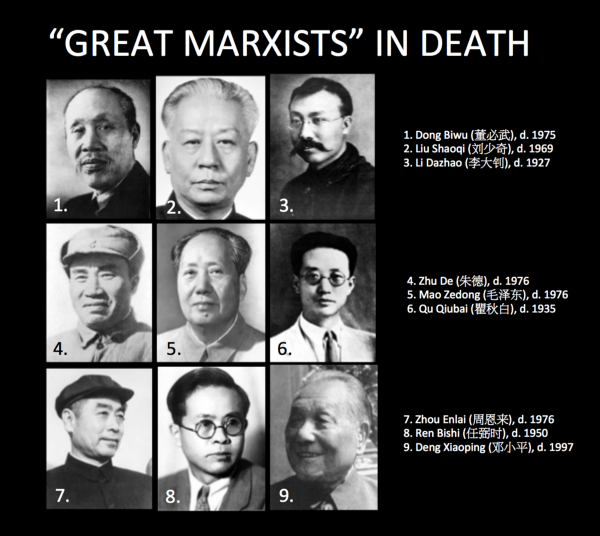

A report two years ago in Jinan Daily, the official Party mouthpiece of Jinan Province, noted five distinct phrases in the official discourse to signal a leader’s adherence to the tenets of socialism. The heftiest of all was “great Marxist” (伟大的马克思主义者).

A report two years ago in Jinan Daily, the official Party mouthpiece of Jinan Province, noted five distinct phrases in the official discourse to signal a leader’s adherence to the tenets of socialism. The heftiest of all was “great Marxist” (伟大的马克思主义者).

Beyond this, in apparent descending order, were: “outstanding Marxist” (杰出的马克思主义者), “staunch Marxist” (坚定的马克思主义者), “faithful Marxist” (忠诚的马克思主义者), and just plain-Jane “Marxist” (马克思主义者).

Only nine leaders in China’s history have been designated “great Marxists,” the last being Deng Xiaoping, who passed away on February 19, 1997.

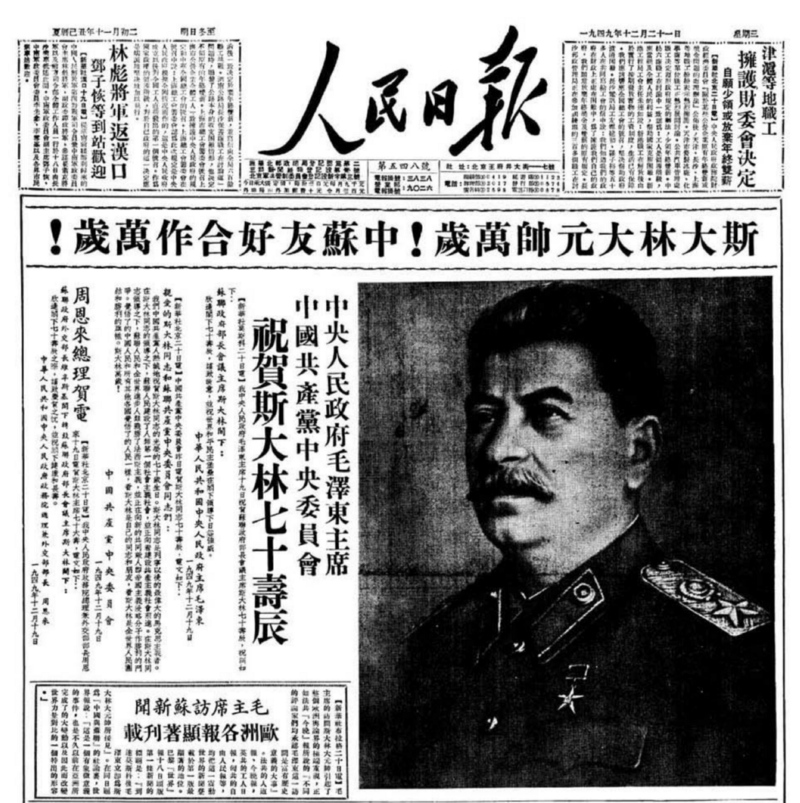

The original “great Marxists” were, of course, Soviet leaders. The first appearance of “great Marxist” in China’s People’s Daily newspaper came on December 21, 1949, Stalin’s 70th birthday, when an article on the front page boomed: “Long Live Generalissimo Stalin! Long Live the Friendship Between China and the Soviet Union!”

This article, three years before Stalin’s death and more than a decade before Mao’s formal denunciation of the “revisionism” of the Soviet Union, brimmed with comradely good feeling:

We of the Chinese Communist Party fervently congratulate Comrade Stalin on his 70th birthday. Comrade Stalin is the greatest Marxist after Lenin. Under the leadership of Comrade Stalin, the people of the Soviet Union have built humanity’s first socialist society, and are progressing toward the realization of a Communist society.

Being designated posthumously as a “Marxist,” the Jinan Daily article observed, is something Party leaders have long regarded as a mark of prestige.

It’s not difficult to imagine that Jiang Zemin, the leader who decided to admit capitalists to the Communist Party, might, when he does pass on, earn distinction as a “great Marxist,” or, at the very least, a “Marxist.”

When it comes to the discourse of the CCP, old habits die hard.

This article, republished with permission, was originally written for medium.com.