The great romantic of 20th-century Chinese poetry, Xu Zhimo

This past spring, I traveled to rural Zhejiang Province to participate in a poetry event. At one of the typically boozy banquets, I was seated next to a local official who, after learning that I’m a translator of Chinese literature, began to tell me breathlessly of the best poet of the last century whom nobody outside of China knew. He lauded the poet’s erudition, his conversancy with Western and Chinese literature, his fascinating life replete with “poetic” exploits with women, and his leading role in dragging Chinese poetry into the 20th century. He spoke in such adulatory terms that I began to suspect that he and this mystery poet were somehow related, or at least lăoxiāng 老乡, hailing from the same hometown.

It turned out that my overly friendly dining companion was speaking of Xu Zhimo 徐志摩, and although he was wrong to assume I had never read him, Xu is essentially unknown in American literary circles. This fact may help contextualize the event about to happen in Manhattan on Sunday, organized by the Renwen Society at the China Institute: a celebration of the 120th anniversary of Xu’s birth and the launch of a new biography written by his grandson. According to the event listing, “This Lecture will be conducted in Chinese, with no interpretation” — the intimidating bold is in original. This is clearly an event for Chinese readers and speakers, which to my mind is a wasted opportunity — a point I’ll return to.

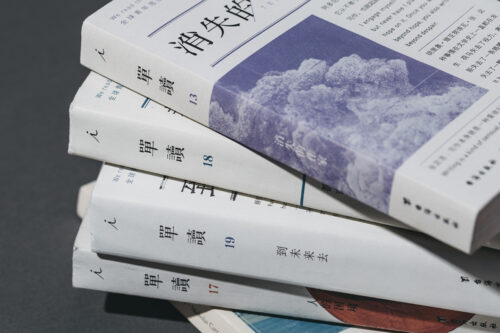

Xu Zhimo indeed has been translated into English, primarily in a volume published by Oleander Press in 2012. The book does not credit the translator(s), which, in addition to being insulting, is a little like a grocery store selling every item in an identical box labeled FOOD: you sort of know what you’re getting, but, really, not at all. And a single uninspiring collection does not do justice to one of the most prominent poets of the early 20th century. Xu was a founding member of the Crescent Moon Society (新月社 Xīn Yuè Shè), which promoted new forms and the vernacular in poetry. He is often mentioned in the same breath with other luminaries as Wen Yiduo 闻一多, Shen Congwen 沈从文, Liu Bannong 刘半农, Bing Xin 冰心, and Hu Shi 胡适. His most famous poem, “Another Farewell to Cambridge” (再别康桥 Zàibié Kāngqiáo, commonly translated as “Saying Goodbye to Cambridge Again,” though there are many translations for this title) is a paean to the River Cam in Cambridge, where he spent a year at King’s College. It begins (translation mine):

Quietly I go,

As quietly as I came;

Quietly I wave

farewell to the western clouds.

The golden willow by the banks

is the bride of the setting sun.

Reflections shimmer on the water

and ripple through my mind.

Brides may have been on Xu’s mind at the time, as he was in the midst of leaving his first wife. At 18, he was compelled to enter into an arranged marriage and managed to father two children while attending college, and traveling to the US (which he hated) and the UK (which he loved) for post-graduate studies. While at Cambridge, he fell in love with Lin Huiyin 林徽因, a woman who would go on to become a well known architect (her niece is Maya Lin), but who was betrothed at the time to the son of Liang Qichao 梁啟超. Xu divorced his wife, a highly controversial move at the time, and returned to China, where he became involved with the painter and singer Lu Xiaoman 陆小曼, who divorced her husband and married Xu. Along with way, Xu is rumored to have had love affairs with other women, including luminaries such as Pearl S. Buck. In the poem “By Chance” (偶然 Ǒurán) he writes (my translation again):

I am a cloud in the sky,

that shadows your stirred heart by chance.

No need for you to feel surprise,

still less to be delighted,

in a flash, every trace of me will be gone.

So it seems. Xu wrote what he lived, and lived what he wrote. To be reminded by these poems of Keats or of Shelley (“I bring fresh showers for the thirsting flowers, / From the seas and the streams; / I bear light shade for the leaves when laid / In their noonday dreams”) is right on target. These Western poets were a direct influence on the Crescent Moon Society, and their Romanticism — a reliance on natural images, gestures toward the sublime, an emphasis on individual sensual experience — became the main model for this innovative group of Chinese poets, Xu primary among them.

This is one reason why Xu is still significant: his work figures into the problem of (Western) Romanticism, and by extension, the problem of Western influence in Chinese literature and culture. Contemporary poets are still criticized for being “too Western,” or the corollary, “not Chinese enough.” I’ve been told of a poet being attacked for “only knowing how to eat bread (面包 miànbāo) and not noodles.” The inverse is true too. In praising a young poet’s work, I heard a senior poet refer to it as “very clean,” by which he meant free from any “foreign” influences.

Outside of literature, many circles, from technology to pop culture to politics, seem to have an irrepressible well of anxiety about Western influence. Whether or not a poet writes in a “Western” style (whatever that is) may seem irrelevant in terms of the larger society, as poetry is often seen as niche. But cell phones are certainly not niche, and the attitudes that make a given poet suspect can also be invoked to encourage a Chinese consumer to buy a Huawei or a Xiaomi instead of an iPhone, or a car manufactured under the Chang’an brand rather than a foreign label. Western brands still carry considerable cachet — I’ve plenty of Porches, Lamborghinis, BMWs, and Mercedes in Beijing and Shanghai. But there is a simultaneous narrative that promotes Chinese industries and products, and it can take on a strident nationalistic tone.

The same is true in the United States, and not just since the last election. Countries have a stake in supporting their own industries; ideologically speaking, we like to shop local, unless we’re buying in bulk, and then we go to Walmart (I’m speaking both of big cities in China and the U.S. on that one). Protectionism looked at from the opposite angle simply looks like keeping one’s own house in order, and on a certain level that may be necessary. But the reverse is also true: if one only looks inward for nourishment, there is a real danger of eating oneself alive.

So Xu Zhimo — who was not only a poet but an accomplished translator into Chinese (among his most famous translations are poems by Rabindranath Tagore, as well as European Romantics and Symbolists) — figures into this more complicated contemporary backdrop. Given not only his considerable talent as a writer, but also the fact that every elementary student in China studies his poetry, his work should be much better known in the US than it is. Why is it not considered basic literary knowledge to recognize the names Xu Zhimo, Bing Xin, and Hu Shi, just as we know the names Yeats, Auden, Millay, Rilke, Szymborska, Lorca, Mandelstam, Marianne Moore? Our own parochialism shows. At the same time, Chinese-only events can also reinforce those cultural gaps. The broader the reach, the better off we all are.

That said, any Chinese speakers in range of the China Institute this Sunday would be well served by attending what looks to be a fascinating event.

The commemorative event Xu Zhimo on his 120th anniversary of birth, organized by the Renwen Society, is this Sunday, November 19, at 2 pm at China Institute (Bianco Room, Pace University, 3 Spruce Street, New York, NY 10038). This lecture, indeed, will be conducted in Chinese, with no interpretation.

UPDATE, 11/18: Readings and a music tribute will be in Chinese, but there will be some English elements, including remarks by Dr. Tony Hsu, Xu Zhimo’s grandson. The event will be live-streamed here.

For more poet profiles: