Q&A with Leroy Chiao, first Asian-American and ethnic Chinese spacewalker and mission commander

From 1990 to 2005, Leroy Chiao took four flights into space as a NASA astronaut, spending hundreds of days off the Earth and dozens of hours strolling among the stars. Since then he has been taking on more terrestrial pursuits, including the launch of a business last year that he hopes can help build cultural bridges between China and the United States.

The first time Leroy Chiao left Earth’s atmosphere, he made sure three important objects joined him on the space shuttle Columbia: a stone carved with the bauhinia flower of Hong Kong, a scroll of Confucian sayings from Taiwan and a tiny flag from the country where his parents were born, China.

“It was something I wanted to do to recognize my Chinese heritage,” said the 55-year-old former astronaut and one-time commander of the International Space Station.

After that 1994 flight made him the 311th human to travel to the stars, Chiao did it three more times during a 15-year career with NASA. In the course of those journeys, he decided on the call sign – a nickname used when communicating during missions – of Shandong, after the eastern Chinese province where his parents were born. He also became the first Asian-American and ethnic Chinese to check off two feats: taking a stroll in space and serving as a mission commander. In 2004, he made history again, participating in the presidential election while aboard the International Space Station. A vote for the leader of the United States had never before been cast from such heights.

Chiao left NASA in 2005. He said he had done everything he desired to do at the space agency, and he wanted to give younger astronauts more opportunities. He also wanted to start a family and try working for himself. Last year he launched OneOrbit, a business providing leadership and team-building workshops to corporations and educational and character-building programs for children. He’s looking for clients in China to connect with his heritage and inspire kids there to visit the United States.

Chiao’s many other accolades include holding a position on the NASA Advisory Council; serving as a special adviser to the Space Foundation; counting himself a fellow of the elite Explorers Club; and being a member of the International Academy of Astronautics as well as the Committee of 100, a group of prominent Chinese-Americans. He speaks Mandarin and Russian “pretty well,” he says. He has a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from the University of California, Santa Barbara. And throw another No. 1 into the mix: He is the first American to visit the China Astronaut Research and Training Center in Beijing, where in 2006 he met the country’s first two astronauts.

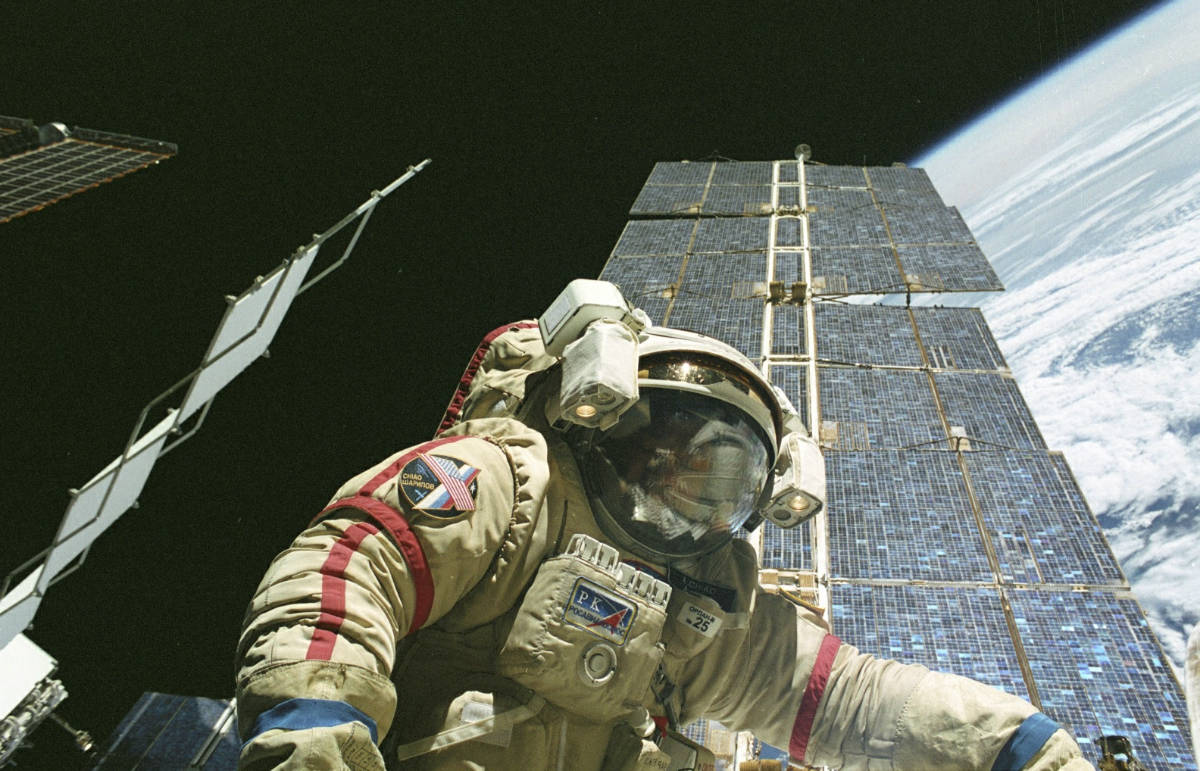

Of the 229 days, 7 hours, 38 minutes and 5 seconds Chiao has spent outside Earth’s atmosphere, he can count 36 hours and 7 minutes of that chunk of time toward what NASA calls EVA – extravehicular activity, or spacewalking.

“Nothing quite prepares you the first time you open the hatch,” he said. “I remember the biggest impression I had was getting outside and taking a look at the Earth and space behind it, and the Earth really felt like a ball.”

Chiao spoke with The China Project about his unique perspective on the planet, his ethnic heritage, space exploration and China’s changing role on this little ball floating amid the stars.

The China Project: What was your first flight into space like, in 1994?

Chiao: I had wanted to be an astronaut since I was an 8-year-old kid watching the Apollo 11 moon landing. Going up on the space shuttle Columbia, it was just, as you can imagine, very emotional, very thrilling. Actually getting up there and seeing the Earth from space with my own eyes was a very special moment. And it was kind of neat, too, because we were flying during the Apollo 11 25th anniversary.

The China Project: Were you feeling any fear or anxiety?

Chiao: What we think about when we’re inside the vehicle getting ready to fly is not so much the risk that something could go wrong. The anxiety is more that something is going to keep you from getting your chance to go, especially the first time. The moment of booster ignition, what I felt, and what I think a lot of people feel, is actually relief. It’s like a huge weight is lifted off your shoulders because once those boosters are lit on the space shuttle, you can’t turn them off. You’re going. You’re going into space.

The China Project: What was your experience of growing up Chinese-American and how has it impacted you?

Chiao: I grew up dual-language. My parents were so hard over on it that if they caught us speaking English at home, they would fine us nickels and dimes to try to make us keep speaking Mandarin. We always lived in mainstream neighborhoods. We didn’t live in a Chinatown. They really wanted their kids to assimilate into Western society as quickly as possible. At home, they maintained some of the Chinese customs and philosophies. They very much instilled in us the Chinese or Asian work ethic, and placing the importance of school above everything else. At the same time, having an open mind to different, new ideas. I think it really benefited me a lot.

The China Project: How has viewing the planet from space affected your perspective on life?

Chiao: What struck me looking down at the Earth is that every part of the Earth is beautiful in its own way. Even things that you would think might be kind of bland, like big deserts – there are so many intricate patterns in the sand dunes. The other thing that struck me is that it all looks very peaceful. Of course, intellectually I knew that some of the places we were flying over, there were probably people dying at that very moment because there is war going on, there is famine and all kinds of suffering. It was always kind of hard for me to reconcile that – the fact that it looked so beautiful and peaceful while knowing there’s a lot of suffering going on. It gave me a bigger perspective on what’s important in life on the Earth. It made me personally not sweat the small stuff anymore.

As far as international relations go, it reinforced the idea that we really should find better ways to partner together. I think the International Space Station is a perfect example of that. We’ve got former Cold War enemies [the United States and Russia], and here we are the two major partners on ISS. Former World War II enemies, some of the European countries, Japan – we’ve all come together and created this incredible civil space project that is the most audacious thing ever conceived and built and operated in space.

When China launched their first astronaut, Yang Liwei, in 2003, they stated very publicly that they wanted to join the ISS program, and it was the United States that rebuffed them. It’s really unfortunate. There were high hopes in the ’08-’09 time frame that we would be able to do something similar with China as we did with the former Soviet Union and better relations through space. I’m still hopeful that can happen, but here we are, 2016, and unfortunately I don’t see that we’re that much closer in many respects, not only space.

The China Project: Many concerns around working with China involve protecting secrets or disagreement with China’s stance on human rights. How do the United States and China manage those issues so they can have, for example, collaborative space programs?

Chiao: When we started working with the Russians, there were similar questions. And we both have safeguards in place. To my knowledge, there has been no improper transfer of technology in either direction. There is no reason to say that wouldn’t also work with China.

As far as human rights go, of course there are issues in China that we don’t agree with. But nobody can say that there are no human rights issues in Russia. Why is it okay to work with Russia? We stand a better chance of influencing their policies and their way of thinking if we’re engaging together as opposed to just “Let’s just try to shut them out and not do anything with them.”

The China Project: What do people need to understand about China to improve the quality of relations with the country?

Chiao: This is an impression I had when I made my first trip to Russia. I grew up in the ’60s during the Cold War. They were always the enemy. I thought of them as one big block of bad guys. Even when I was at NASA, I was older, I was in my mid-30s when I went over, and I still carried some of that prejudice. What I found was that it is not one big block of bad guys. They’re all individuals. They’re nice people. I’d say most Americans think of China as one big block of bad guys – they’re out there to become the number-one economy, take all our secrets and make shoddy stuff to sell to us. I think that’s the general impression. How do we get over that? If more people could travel to China and see with their own eyes and see it’s not just one big block of bad guys – that people are people. There are a lot of good people. There are some bad guys, but there are a lot of good people. The central government doesn’t help itself sometimes. But all governments put their feet in their mouths sometimes.

The China Project: What does China need to understand about the United States?

Chiao: Somebody told me some time ago that 90-plus percent of the politicians in this country are all lawyers. And 90-plus percent of all politicians in China are all engineers. Quite different backgrounds. I’m an engineer, and we tend to think pragmatically and look for solutions and expedient and efficient ways of doing things. China has to understand that the U.S. is different. Our politicians don’t think the same way theirs do. That’s the mistake everyone naturally makes. We assume the other folks in a different culture, in a different country, think the same way we do. We don’t have a central committee like they do that can make absolute decisions. No matter what the president wants to do, if the president can’t get the Congress to go along, it’s not going to happen. And vice versa. This is all a very different system than they’re used to, and they have to understand that. I think they understand Americans – we’re all different. I don’t think they look at us as one big block. I think that’s more of a Western perception of Asia.

The China Project: How does China’s Internet censorship affect the country?

Chiao: My philosophy on all that is if you’re governing well, you shouldn’t be afraid of being transparent. You shouldn’t be afraid of people writing opposition pieces because if they’re not correct, if they’re not true, it will very quickly sort itself out, just as it does in the West. On a personal level, it’s always a pain when I go over there and I can’t use my Gmail [laughs].

The China Project: What does the future look like for the space programs of China and other countries?

Chiao: What we, the U.S., are doing is shooting ourselves in the foot. China is going to launch the first element of its space station in 2018. They’ll be operational by 2020, and then they’ll be complete by 2022. Two years ago, there was a major aerospace conference in China, and I was there. China was openly courting the entire world to come work with them on their space station and their space program, including flying other countries’ astronauts to their space station, in addition to doing collaborative research projects. Every one of our International Space Station partners took meetings with China to talk about the future with them. If we’re not careful, all our partners are going to go work with China and Russia. And what are we going to be left with? I personally think that retiring the space shuttle was the wrong thing to do. Here we are without the ability since 2011 to launch our own astronauts into space. If we’re not careful, we’re going to find ourselves isolated, and the rest of the world has moved on to work together internationally.

The China Project: How does China factor into your future plans?

Chiao: As far as space goes, I’m very limited on what I can do in China based on U.S. law. Even if it’s not classified, if it’s not in the published literature – anything about aerospace – I cannot discuss [it] with any foreigner, whether they’re Chinese or not.

There is another thing I’m working on: I’ve got a company called OneOrbit. It’s about training solutions for kids as well as corporations. We’re really excited about the possibility of getting into China. It has a lot to do with my heritage and wanting to go back there and help to be a bridge in some way.

The China Project: What is a distinctively Chinese accomplishment that will benefit the world in the next five years?

Chiao: I don’t know if I’d call it a distinctive Chinese thing. It’s an open secret that China wants to land its astronauts on the moon. The moon has such significance to China and Asia and Asian cultures. I don’t see them not landing astronauts on the moon. They may land someone on the moon by 2025 or 2026. That I think would be pretty stunning.

The China Project: What is your favorite Chinese food?

Chiao: I love dim sum – chicken feet. I also like the steamed beef tendon.

The China Project: What is one of your favorite offerings from Chinese culture?

Chiao: Something that my son has really enjoyed and I liked it too is “The Monkey King.” We’ve seen different performances of that.