Black Panther in China: A red carpet opening night near Tiananmen Square

Walking into the Tiananmen Poly International Theater felt like slipping through some protective barrier and entering Little Wakanda in Beijing.

Images courtesy of OPOPO

On Friday evening, March 9, more than 400 people gathered in the shadows of Tiananmen Square to watch a nation known for isolating itself from the outside world prepare to enter a new era. A new king was about to be crowned, one with ambitions of growing his country’s influence beyond its borders.

No, it’s not what you’re thinking. The nation I’m referring to is Wakanda, and its new king is T’Challa, the Black Panther. This past Friday, the newest Marvel superhero movie made its debut on mainland Chinese screens. Beijing’s black community came together to celebrate the opening with a red carpet event put on by OPOPO Magazine, a Beijing-based WeChat platform that tries to promote positive images of Africa and its diaspora.

Walking into the Tiananmen Poly International Theater on Friday night felt like slipping through some protective barrier and entering Little Wakanda in Beijing. The place was pulsating with vibranium levels of excitement.

I was met by several event organizers donning elegant robes made from African textiles and head wraps sitting like bouquets on the women’s heads. Nubian gold sparkled on eyelids, wrists, and scepters. Even though I had broken out my Ghanaian print bolero jacket and tried to channel my best Afrofuturistic Solange with my hair, I felt woefully underdressed as attendees began to strut down the red carpet.

OPOPO, which stands for “One People, One Purpose,” was founded in 2016 by Rhianna Aaron, an American living in Beijing who wanted to fight the negative portrayal of black people in Chinese media.

A week prior to the event, I met Aaron at a dumpling restaurant. She wore Ankh earrings the size of mahjong tiles, and her nails were painted with the Ghanaian flag.

“This movie is so much more than just a movie,” she said. “Not only is it an opportunity for black people to feel so much pride, it’s also a chance for China to see other sides of black culture outside of stereotypical representations. Everyone gets to celebrate with us.”

The red, black, and green colors of the Ghanaian flag on Aaron’s nails made a cameo in the Black Panther movie. At the beginning of one of the most badass fight sequences in the film, Prince T’Challa is dressed in black, his ex-girlfriend Nakia is in green, and his right-hand woman warrior Okaye is in red when they walk side by side into a South Korean casino in pursuit of Ulysses “Klaw” Klaue. These colors are the colors of Pan-African Unity, and they are used in the national flags of 22 countries in Africa, the Rastafarian flag, as well as some “alternative” flags made by black people in America.

Pan-African unity might seem like an odd theme for an event held footsteps away from the Forbidden City. But like Wakanda, the black community in Beijing may be secretly gathered in our own techno-utopia. For us, though, the technology that has allowed us to build our community is WeChat. Beijing is home to a number of black and Afrocentric WeChat groups and WeChat media platforms, such as No Name Podcast, Africa 2.0, and the Appreciate Africa Network, just to name a few.

During our lunch, Aaron told me, “Being positioned here in Beijing specifically and China in general puts us [the black community in Beijing] in a unique position, especially among the expat community, seeing that we can connect with so many people from so many different countries.” Like Aaron, I am also a black American, and living in China has given me the opportunity to meet people from our homeland and our whole diaspora: from America, the Caribbean, and the continent of Africa.

The community was out in full force on Friday. As people lined up for their red carpet photo shoot, I took to the sidelines to ask attendees about their choice of attire. Their answers were more interesting than anything anyone at the Oscars has said about Versace or Dolce and Gabbana. Their stories reflected genuine excitement for a movie of this magnitude representing black characters, the first of its kind to debut in China.

“I looked up what people in Wakanda wear. That’s where I got the dots. Then I just mixed and matched. I’m really happy that something like this is happening here. We get a chance to showcase everything we can dress as, everything we can do. It’s a really proud moment for us black people and black people in China. These opportunities are pretty rare, so I’m happy that this is happening.

“The white inner part of my outfit is a kanzu, and we usually wear it for traditional ceremonies like marriages and introduction ceremonies. Usually you wear a coat over it, but this time I decided to fashion a robe from kente. This pattern is quite West African, and I’m East African, but I thought it looks cool.”

— Emmanuel Kyeyune, from Uganda, left in photo above

“We were in Ghana together for Spring Festival and we had our outfits tailor made for this event. We shopped together at a market downtown to select the kente pattern, lace, and polished cotton. Then we decided on the design and told the seamstress what we wanted.”

— Rhianna Aaron, pictured above with her boyfriend, Clifford Fagariba

“This isn’t the first African print outfit that I’ve made here, but this one I did have specially made for this event. There’s a tailor in Tayuan Diplomatic Residence Compound. There are a lot of African embassies, so the tailor had a lot of different African fabrics and patterns. My husband’s really into the comics, so drawing off of what he knows, I just went with what I felt worked best for me.”

— Leandra Campbell from the U.S. Embassy, left in photo above

“I made my outfit myself. I’ve had the fabric for a long time, so I thought I’d put it together for this event. I sold the pants I was wearing that very night. A lady loved it more than me, so I hopped into a taxi, took it off, and gave it to her.

“I don’t even know her.”

— Andrew Charles, from Antigua and Barbuda, right in photo above

“Like Killmonger, I could never really be Wakandan.”

Note: Movie spoilers appear in the sections that follow.

It was more than a year ago that Aaron began thinking about turning the Black Panther premiere into a major event. “I’ve never seen a movie like this on this level with a nearly fully black cast and also celebrating and featuring realistic depictions of Africa,” she said. “When the actual movie trailer came out, I published it through OPOPO and said, ‘Look, guys! It’s coming!’”

There were, however, reasons to question Black Panther’s ability to make it to the mainland.

“In the U.S. edition of the Star Wars [The Force Awakens] poster, [black actor John Boyega] was prominently featured, and then when it came to China, he wasn’t even there in the poster,” Aaron said. “Having that knowledge had me wondering if they were really going to bring Black Panther — like, the most blackest black black movie — to China. That was surprising that they do see the value in it and were not quick to dismiss it.”

Aaron made sure Black Panther received a fitting welcome.

At the OPOPO Beijing event, Chinese people accompanied their black friends and family wearing traditional African cloth, rocking braids, and donning head scarfs. I saw it less as appropriation and completely as a way to join in on the celebration. The costumes, languages, and hairstyles in Wakanda are a blend of different African cultures, and the Chinese people in the room were often family or close friends of the black people the event was tailored for. To me, the “best dressed” of the night went to a mixed family whose outfits were designed by the husband’s mom in Nigeria:

But plenty of others brought it as well:

“I’ve had people outside the black community ask me, ‘Is it okay if I come ’cause I’m not black?’” Aaron said. “And I say, ‘Yes, of course.’ And then they ask me, ‘What should I wear?’ I think it’s beautiful that there’s so much support around the movie. Personally, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with you putting on some dashiki or kente, but also it’s not a requirement.

“I think people are well aware that this is a special moment for people of color, especially black people of all countries around the world. And I think people are ready to celebrate with us and realize the significance of this.”

After everyone had posed for their professional photos, our contingent of 400-plus entered a large theater, where Ugandan djembe drummers warmed up the crowd.

Aaron gave a Chinese movie theater employee who helped organize the event a shirt that read “黑是美” (hēi shì měi), i.e., “Black Is Beautiful.” The overhead lights dimmed, and we all put on our 3D glasses for the main event.

I was excited to be surrounded by black people to watch this superhero written about black people. Some parts in the movie felt universal to the global black experience. One of the lines that elicited the strongest laughter was when Shuri (played by Letitia Wright), startled by a white American CIA agent, jokes, “Don’t scare me like that, colonizer.”

Likewise, in the scene where Shuri, Nakia (Lupita Nyong’o), and Ramonda (Angela Bassett) visit the neighboring kingdom to ask for help, once the white man begins to speak, his words are drowned out by barks. Uproarious laughter filled the theater.

There were several moments that felt like Easter eggs just for the global black community. When Shuri points to T’Challa’s ugly sandals and screams, “What are those?,” it was a reference to a Vine meme popular among young black people. My non-black friend turned to me and said, “I’m going to start saying that.” SMH.

While it was fun to unite over the comedy, uniting over trauma is something our global black community does well.

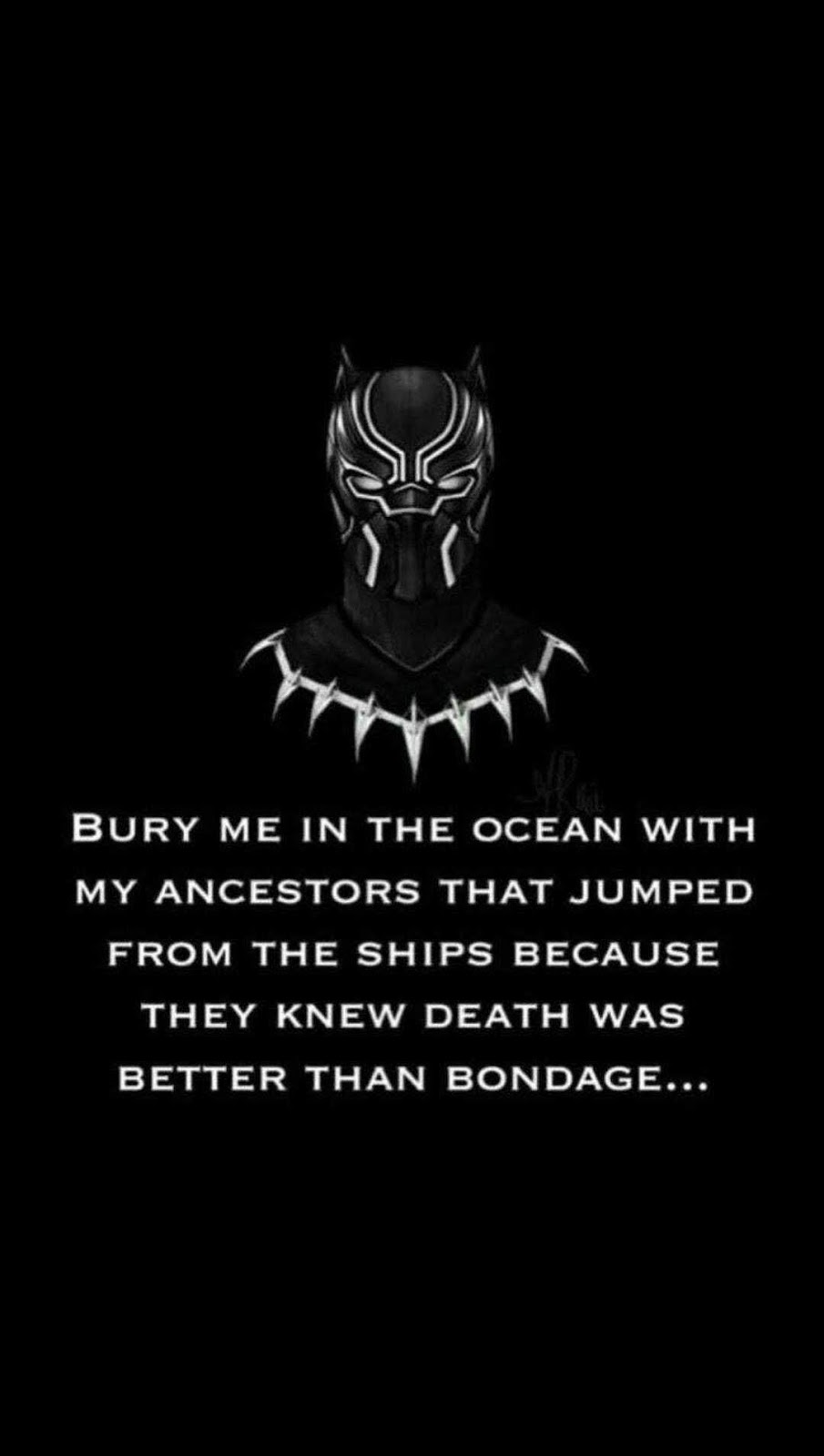

Killmonger’s last line — “Throw me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped off the slave ships because they knew death was better than bondage” — left me, as a descendant of slaves in America, in tears. In that theater in Beijing, surrounded by “one people” — my people, wearing their full African cloth, knowing proudly where they came from — I knew what had separated me from “my Wakanda” were those slave ships. Like Killmonger, I could never really be Wakandan.

Rebecca Mazie, far right in photo above: “[My husband] Clyde’s from Cote D’Ivoire (Ivory Coast)…we chose these because it’s the same colors as the Ivorian flag. Our son really likes superhero movies, and he got really excited at the trailers for Black Panther. It’s nice for him because it’s an African thing.”

Clyde: “Not just an African thing, it’s a black thing, so let’s put it that way. I’ve never seen a movie that portrays such positivity about black communities worldwide. It truly represents us, and we’re trying to live up to the potential that the movie’s trying to portray about black lives.”

Rebecca: “It’s so special. When we were driving here, we were driving past the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square, and our son is so excited to live in China and to see all of these things. It’s really special that he gets to mix all of these different things together for his life.”

“Perhaps I just don’t understand what’s less crude or less overt about an unarmed black man being shot in the back while in handcuffs.”

More than a few think pieces have been written about Black Panther, and you can bet there have been articles about the movie’s impact in China. But I take exception to those that ask whether Chinese people can “accept” a “black” movie.

Niesha Davis, writing for Sixth Tone, paraphrased Langston Hughes to say “life for most black people in China isn’t a crystal stair” (a line from a poem he wrote that has nothing to do with China, in which the poet’s mother tells her son about her hard life). But Langston Hughes himself wrote in I Wonder as I Wander about how much better he was treated by the Chinese people in Shanghai than he was by the white colonialists in the city’s French Concession district. Davis says the racism she experiences in China is “cruder and more overt,” yet her examples are hardly China-specific: skin bleaching, eyelid-crease plastic surgery, employment discrimination based on race, portrayal of Africa as a poor “country” in need of saving.

Perhaps I just don’t understand what’s less crude or less overt about an unarmed black man being shot in the back while in handcuffs. This was the subject of Fruitvale Station, the first film that Black Panther screenwriter/director Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan, the actor who played Killmonger, collaborated on. The Public Enemy poster in Killmonger’s dad’s apartment is a fitting reference to the status of black people in the United States: public enemy number one.

Antiblack racism is a global phenomenon that is no worse in China than in other countries, and we are seeing the movie Black Panther ignite a global movement in response. In Brazil, black Brazilians intentionally went to movie theaters in majority white Brazilian neighborhoods to see the movie together. #WakandaDubai sold out of tickets for its premiere event that encouraged cosplaying. Killmonger-inspired memes in South Africa have been made in response to recent news that South Africa would expropriate land from white farmers.

All of these “China’s take on Black Panther” articles reference the same recent Chinese media blunders of the last two years in an attempt to claim that racism “pervades” Chinese media: the Qiaobi detergent commercial that featured a black man being “cleaned” into a Chinese man, and a skit in the annual Chinese New Year variety show that involved blackface with grotesque props giving them bigger butts and boobs. Other data points come from screengrabs from sites like Douban (this led Quartz to actually write, in a facile headline, “Chinese moviegoers think Black Panther is just too black”).

In the end, my objection is these pieces don’t reflect the enthusiasm and nuanced perspectives from Chinese people about this movie, at least from what I can tell on the ground here in Beijing. “The actors were super handsome and cool, both the good guys and the villains,” Zhang Xinyan told Global Times. “I liked that the bald female warriors were so fierce. This movie doesn’t show black people the way Hollywood used to, but in a larger variety and in the context of African tribal culture. It is very rare for the average Beijinger to come in touch with these tribal elements. We definitely lack an understanding of African and black culture.” Rhianna Aaron herself noted before the event, “Honestly, speaking to people in all communities, not just the black community but Chinese as well, many people are excited.”

Ticket sales have backed it up: Black Panther took top spot in China’s box office, earning $66.5 million in its opening weekend, more than in any country outside of the U.S.

“This piece is made by a friend from my church. It’s black and silver because it’s a royal occasion. We’re celebrating the kingdom of Wakanda, so I wanted something that is very vibrant but also represents Africa, which to me means luxury, excellence, and beauty.”

— Ciata Momoh, from the U.K., standing middle in photo above

“My piece is also made by the same lady [that made Ciata’s], who is Congolese. I’m excited to put on this African attire today.”

— Heather Yixuan Li 李依轩, from Beijing, second from right in photo above

“I’m wearing something made in Senegal. My mom designed this. Everybody was telling me this is the event, and I had better come with my best African outfit. I’m from Cameroon and the Caribbean, so I wanted to wear this dress to show my Africanness.”

— Canelia Mbida, far right in photo above

“Someone even said Killmonger could well be viewed as Xi Jinping, though this is likely not what Coogler was intending.”

On my way to the after-party, I texted my American-born Nigerian friend whom I met in Beijing, who was at a similar Black Panther viewing in Shanghai. We both referenced our tears, and she said, “I’m so mad this is the history of our people. Everything was taken from all of us. We’ve never stood a chance.”

Killmonger’s final line was widely shared in the 363-person-strong WeChat group for the Beijing Black Panther event. Discussions centered on some of our biggest debates in the black global community. At times, we try to embody “One People, One Purpose,” which OPOPO had brought us together to celebrate. Other times, we can’t ignore how history has highlighted the contradictions in such a sentiment.

Perhaps the biggest unifying factor of Pan-Africanism is our experience of colonialism under European nations, Britain in particular. To us, the white British lady in the museum of African masks in London was a clear stand-in for this legacy. I wasn’t the only person rooting for her death because of what she symbolized: Each of those masks represents an African civilization the British violently colonized and stole from — not just masks, but people. Again, another sentiment delivered by Killmonger.

In the days since the event, conversation has continued to flourish in the WeChat group. Topics have run the gamut:

Did people think that #KillmongerWasRight for trying to liberate the global black community with violence?

Are black Americans the real Wakanda because they have access to more technology?

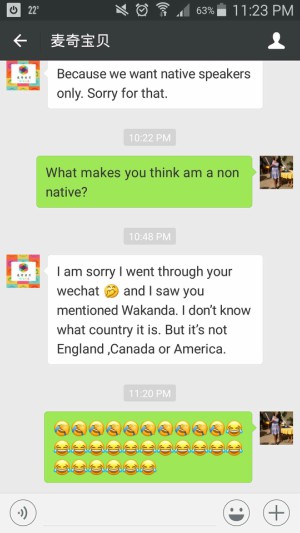

Someone sent this humorous interaction with a recruiter:

I also enjoyed opening a digital hongbao — a red packet (of money) sent into the group — that came packaged with the phrase “Complicated World” to reflect the complexities Black Panther has brought to the forefront.

My Asian-American friend Phong Quan wanted me to add him to the WeChat group so that he could stay updated on the red carpet photos. After a day of discussions, he expressed sincere surprise about the movie’s layers. “I loved the movie and thought it was important from a representation perspective,” Quan said, “but I didn’t realize how much care [the movie] took to reflect the diversity of experiences and ideas in the black diaspora — or really even that the black diaspora was a thing — until I saw these super-passionate discussions and debates in the WeChat group about it. It was honestly very inspiring and made me think more about my own Asian roots and what it means to me.”

I asked how Shuri’s joke of calling the CIA agent a colonizer was translated in the Chinese subtitles, to which someone responded, “I hope you won’t be using that phrase on the Chinese after they’re done colonizing.” A sure reference to the fact that China is investing millions in “infrastructure projects” and coal plants in African countries like Kenya.

Seeing this movie in China adds that extra dimension to the movie. Eileen Guo, writing for The Outline, interviewed a Chinese college student, Yang Yang, who felt that, more than anything, the film espoused “the universal values of the United States.” She explained how, at the end of the film, T’Challa had gone from “saving the people of his country” to “exporting technology” to the rest of the world — “much like how the United States operates in global politics.”

The ending, like most American-made superhero movies, is propaganda lite for the way the United States exerts its soft power over the world. But being in China added an extra dimension to the “global politics” conversation.

Along with the infrastructure projects, China has begun attempting to exert its soft power in Africa. News media sources like Star Times were present at the event. Star Times reports news about the African community in China and also dubs Chinese TV shows and movies into English for the African audience. China has also been establishing Confucius Institutes to educate people about Chinese culture and values. Someone even said, tongue-in-cheek, Killmonger could well be viewed as Xi Jinping — though this is likely not what Coogler was intending.

Which brings me back to the Pan-African colors of the Ghanaian flag on Rhianna Aaron’s nails. If we are “one people,” what is our “one purpose” in China?

One of my favorite think pieces on the Black Panther film was written by Clint Smith III when he asked the question, “What would W. E. B. Du Bois make of Black Panther?” in the Paris Review. In the article, Smith speaks about “the intergenerational thrill experienced by families of every hue ornamented in African garb, an array of spectacular patterns and colors exploding across theater lobbies from Atlanta to Oakland.”

But what about the theater lobbies from Accra to Beijing?

Du Bois fought his whole life for a moment like our little event in Beijing. He wrote a letter to European leaders in 1900 at the first Pan-African Unity Conference appealing to them to struggle against racism, to grant colonies in Africa and the West Indies the right to self-government, and demanding political and other rights for African Americans. They had met in London — where Killmonger goes to “steal” the masks and vibranium from the white woman who is the “expert” on African masks.

Du Bois and his wife, Shirley Du Bois, visited Beijing, and you can see photos of them laughing with the same cherub-cheeked Chairman Mao whose 15-by-20-foot oil portrait was hanging less than a mile away from our theater on Friday night.

Du Bois eventually renounced his U.S. citizenship and is now buried in Ghana. His wife, Shirley, went on to form a lasting relationship with China, and she chose Beijing as her final resting place. Her grave is out in the farthest reaches of western Beijing at the Babaoshan Revolution Cemetery.

I’ve been meaning to make the trip out to visit her grave for a while now. Like T’Challa and Killmonger, I realize the importance of talking to our ancestors.

When I do end up visiting, we’ll now have a lot to talk about. Did she think that #KillmongerWasRight? What would she have worn to go see the movie? Is she concerned about her adopted country’s colonial ambitions? No matter what, I’ll be sure to bring the popcorn — the sweet kind that moviegoers in China like.