Kuora: Mastering Chinese tones with ‘the Dude System’

It’s easy enough explaining the differences in the tones in Mandarin Chinese, but it’s a whole other matter for language learners trying to remember exactly how the tones sound. Kaiser can help. Here, he answers a question originally posted on Quora on December 22, 2014:

How do I master Chinese tones?

True story: When I was a grad student in the States, I worked as a teaching assistant for a lower division course called “Chinese Humanities.” One of the early units was on the Chinese language, and the professor would spend a lot of time focusing on the peculiar properties of the spoken language. He explained to these young scholars how Chinese is “a phonemically poor language, augmented by the use of suprasegmental phonemes.” What he meant was that there aren’t a lot of basic sound units in Chinese until you add the tones. Those tones scare a lot of folks off of learning Chinese. Call them “suprasegmental phonemes” and you can scare ’em off a class on Chinese Humanities as well, which may have been the professor’s intention anyway, since the course was overenrolled.

“We have them in English, too,” the professor said. He meant tones. “If I were to point out that window and say, ‘Look at the bluebird,’ it would mean something fundamentally different than if I were to point out the window and say, ‘Look at the blue bird.’” But this ornithological distinction was lost on many students, who were still struggling to write down the word suprasegmental and wondering, “Is this going to be on the quiz?”

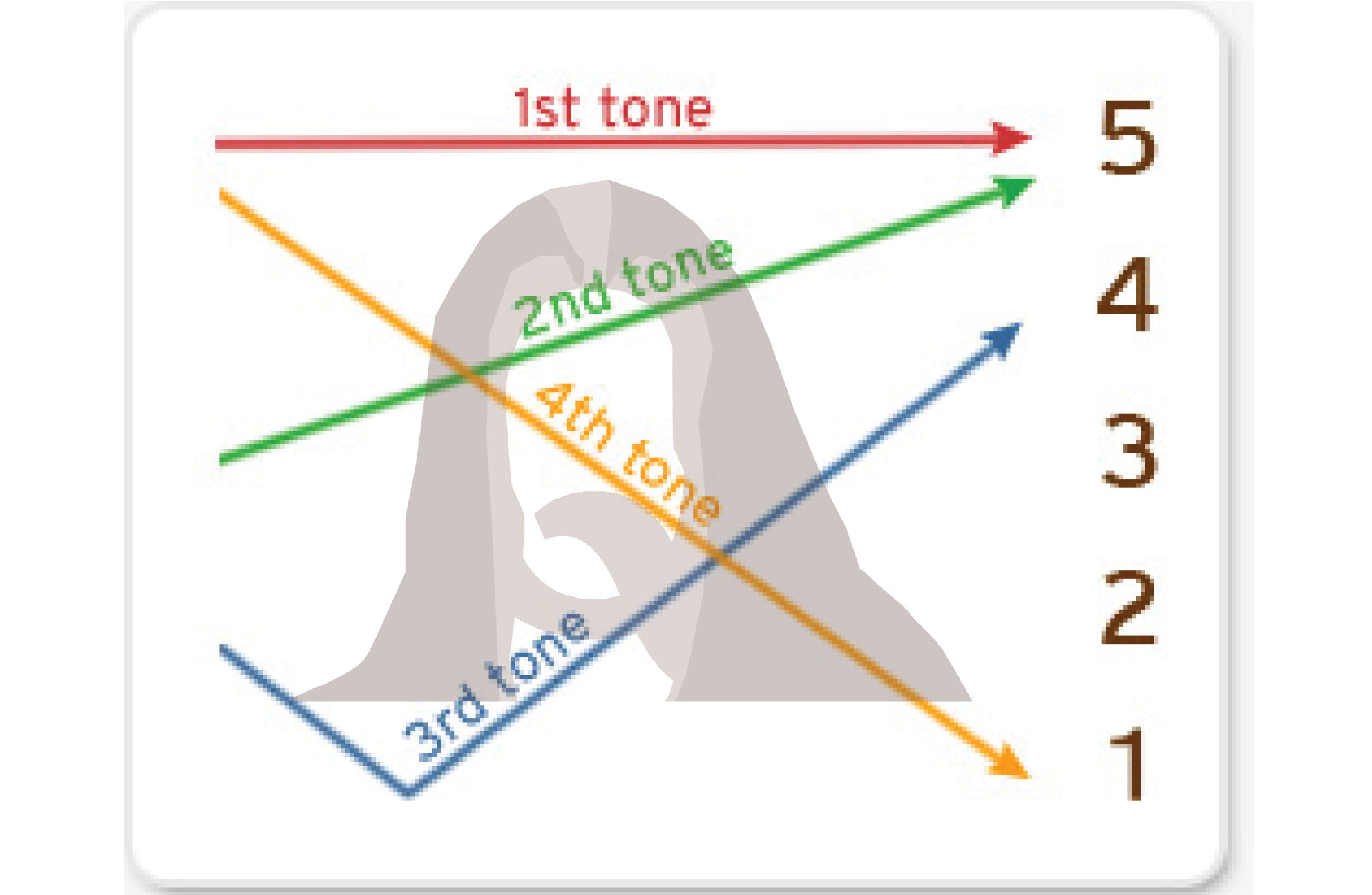

Sympathetic to their plight, I reviewed this whole business of tones in the sections I taught, and came up with my own explanation — one closer to their hearts. I called it the Dude System:

First Tone: Dūde — the disapproving tone, as to the clumsy roommate who’s just knocked over your three-foot Graphix and gotten bong water all over your Poli Sci 142 reader: “Dude, I can’t believe you spilled my bong again!”

Second Tone: Dúde? — in the concerned but creeped-out way you might address the roommate you discover sitting naked and cross-legged in the dark, chanting “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” and sounding a little brass bell.

Third Tone: Duǔde — scornfully, as if your roommate has asked to borrow $50 so his sensei can align his chakras: “Yeah, right, dude.”

Fourth Tone: Dùde! — as if you are exclaiming in triumph to your roommate when coming home from class having gotten a date with mega-babe Elena from your macroeconomics class.

It worked, I suppose, though I regretted having taught it that way when I’d get quizzes back with some version of my Dude System repeated under the question on suprasegmental phonemes. Yeah, tones are hard for lots of people. I’ve known plenty of Mandarin students who can’t get them right unless they draw marks in the air with a finger as they speak, like some developmentally challenged conductor. No shame in that.

Rote memorization’s a bitch, too. In 1988, when I first came to China on my own, I enrolled at what was then called the Beijing Language Institute (BLI). I had a rudimentary grasp on the grammar — a vestigial memory from childhood Chinese at home and Saturday morning Chinese school, which I hated because it forced me to miss all the good cartoons. And being a decent mimic, I could at least say the few things I knew with the right tones. Idiot that I am, I tried my best when talking to the placement officer at BLI, and they stuck me in a class with a bunch of Germans and Koreans who all spoke atrociously but had thousands of characters at their command.

I knew maybe 50 — 10 of those were the first 10 digits, three were the characters in my name, and the rest were characters like big, small, sky, man, sun, moon, me, you, him, and that sort of thing. My teacher, having great faith in me, handed me a box full of flashcards and told me to hole up in my dorm room until I had memorized them. My time as a student at BLI was short indeed: I ended up learning Chinese from miscreant Beijing rock musicians who make cabbies sound like masters of Mandarin elocution. But I did learn to speak.

In grad school, I tried to learn Chinese properly, though it wasn’t until I had dropped out and come back here [to Beijing] to live that I learned to read, and only then by a mysterious osmotic process involving — I ruefully admit — TV subtitles, karaoke, and pinyin on road signs. But one day about five years ago, I picked up a paper and discovered that, a handful of characters aside, I could basically read.

And so I was ready to tackle chengyu. They’re really very cool — the sine qua non of real fluency in Chinese, I thought, steeped as they are in history and lore. I bought a couple of chengyu dictionaries, one organized alphabetically, beginning with chengyu that start with “ài” (爱) in pinyin, and the other organized by number of strokes. Tackling them, as I have, from the beginning of the dictionary, I’ve now mastered a total of four chengyu, two of which begin with 爱 (ài) and the other two beginning with 一 (yī). So should the occasion arise, I can say the Chinese equivalents of “Love me, love my dog,” and revile those alike in villainy as “jackals from the same hillock.” I feel just like this character in an Edith Wharton short story I once read: She sits through pretentious book club meetings waiting for an opportunity to use the one literary allusion from Appropriate Allusions for All Occasions that she’s committed to memory: “Canst thou draw out Leviathan with a hook?”

Today, I can even write in Chinese — with a computer, that is. I’m totally dependent on predictive text input. My pinyin has always been good, despite my mother’s inability to differentiate between sh and s. Since I can read, I can sort of type, but ask me to actually write anything by hand and I’m hopeless. When an out-of-town visitor asks me to write down the name of his hotel, or some bar, or a restaurant, I break into a cold sweat: there goes my facade of China expertise. You don’t know how many times I’ve resorted to using the “compose SMS” function on my phone to figure out how to write a fairly common word.

Tell me you haven’t done the same thing. See, dude? (that’s second tone) — we’re all jackals from the same hillock.

Kuora is a weekly column.