Searching for jazz in Shanghai

Photo by Zheng Kaimin

“I just follow music and do what I want.”

Midnight passes, and the lights are turning out. Morning’s arrival is early and respected here. Still, the city wouldn’t be itself without its velvet lounges unscathed by sunlight, inconspicuous as they may be until entered. The restless of Shanghai are always wandering, seeking places like these to land. Above all else, they seek rhythm.

There’s a place near People’s Square, where outside, buddies hoist Tsingtao beers and pass cigarettes. Ascend a round staircase and walk through reception on the third floor to enter. The lounge, known to the world as Shake, is arranged so that all patrons — from the window-side diners to those at the bar — can turn toward the stage. On this night, there are keyboards, drums, guitars, percussion, and brass. The band that plays is unified and never departs from a hook or rhythm for too long, for they have a directive: Make people dance.

Is this a jazz jam? Not exclusively so, but it could not exist in essence apart from jazz. The musicians, hailing from Brazil, England, Mauritius, China, and New York, all share a heritage in jazz training, as their performance makes evident. All of them are either guests or mainstays at some of the half-dozen or so other jam sessions around the city, such as Chair Club or JZ Club. The trombonist, a young, stylishly spectacled Chinese man, now teaches jazz performance at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, proof that the art has made its way into the nation’s finer institutions.

A Cameroonian native raised in Versailles is the evening’s host — the evening is named after him, in fact. “John Jam Session” has been happening in Shanghai for more than a decade, and on this night, the man known as “John Shanghai” is wearing an “In Black and Happy” shirt (from his organic clothing line) and working the crowd. His mission? “Be together and have good health,” he says.

Born John Nguidjol, John Shanghai is the indispensable life of the party at Shake. He stays a length of the evening on lead mic, but nearly as much of his time is given to swiveling with strangers on the dance floor, talking up old friends at the bar, and recruiting audience members to join the ensemble themselves, including veteran singers and musicians and amateurs alike. “When people come to a live show, they expect something fun,” John remarks with a smile.

Born John Nguidjol, John Shanghai is the indispensable life of the party at Shake. He stays a length of the evening on lead mic, but nearly as much of his time is given to swiveling with strangers on the dance floor, talking up old friends at the bar, and recruiting audience members to join the ensemble themselves, including veteran singers and musicians and amateurs alike. “When people come to a live show, they expect something fun,” John remarks with a smile.

For many, he’s like a modern, funky Comte St. Germain — a vivacious, seemingly ageless personality and raconteur who impresses all despite being known by few. (OK, maybe he just seems that way to me.) As he told me over coffee, he actually enjoyed being a relative unknown on the Shanghai music and lightlife scene when he first arrived in 2005, having come because “eight out of 10 friends” in Hong Kong claimed Shanghai was going to be the next big scene in Asia. But after a dozen years, John’s made a name for himself.

“When people talk about Shanghai, live music, they think of jazz,” John says. “Jazz music is…natural. Not easy, but an obvious choice…100 years ago, (the scene was) jazz.”

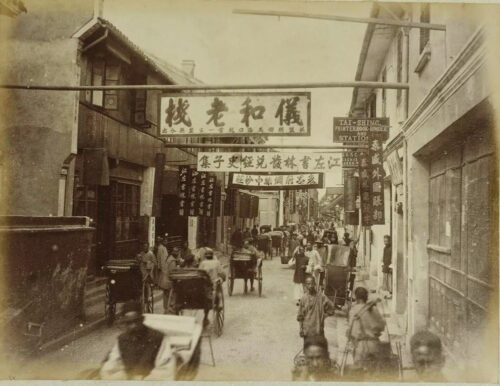

Jazz was indeed popular in Shanghai in the 1930s, a fact remarked upon by none other than Langston Hughes — the poet laureate of Harlem — who wrote about it in his autobiography I Wonder as I Wander. As told by the website Historic Shanghai:

“Shanghai seemed to have a weakness for American Negro performers,” from Nora Holt at the Little Club, Midge Williams, Valaida Snow at St. George’s Nightclub, Earl Whaley, Buck Clayton, and Teddy Weatherford. Most performed in the French Concession nightclubs like the Canidrome because the French did not apply American race laws in their Concession. Hughes spent time with Teddy Weatherford, who headed “the best American jazz band in the Orient”. He reflected that were he a performer like Teddy, he would “never go home at all”, but alas, Shanghai was too expensive a place for a mere writer to linger.

John Shanghai, meanwhile, is aware that the present-day scene isn’t of quite such renown — and has himself noticed changes from very recently. “Today, it is more difficult to be a jazz musician in Shanghai than five or 10 years ago,” he says. “There are less musicians in Shanghai now.”

The reasons are various. Music “is not a priority” for the leadership and power brokers of influence and investment in Shanghai, John says. “It’s never been.” Moreover, the paperwork process necessary to legally keep foreign talent on the mainland can be tenuous and unpredictable.

Gaining international recognition for the Shanghai scene has also been tricky. With fewer foreign acts as headliners, local acts have found themselves with larger spotlights to fill, and sometimes they aren’t entirely ready. Still, John touts the courage of venue managers and arts-minded entrepreneurs who take risks on artists and make sure up-and-comers have somewhere to play. Wooden Box, Heyday, The House of Jazz and Blues, and JZ Club are among jazz patrons’ most frequented.

More than overcoming the challenges of regulations or censorship, John considers keeping up with the times to be the biggest determining factor in one’s success or failure in Shanghai. He recalls a number of grandiose gigs that ran for a short duration before exhausting their lifespan, starved by a failure to innovate. In a city infamous for transience, one-hit wonders are aplenty; it’s only those who possess a feverous energy who create performances that are continually in demand. Eclectic brass-blower Alec Haavik comes to mind, having used out-of-the-box compositions and eclectic fashion statements to find a niche and make waves within the Shanghai jazz scene over the past decade.

The fact that jazz was hot in historic Shanghai is neither disputed nor secret. There is a classic local venue, the Fairmont Peace Hotel, still paying tribute to that golden era of the 1920s-30s with a daily show, featuring performances of jazz standards and Shanghainese classics from a band whose average age is 82 years old. As SCMP reports, “Former U.S. presidents Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan are among the dignitaries who have dropped in for an evening of jazz — Clinton, who plays the sax, even joined in.”

Readers are obviously encouraged to go and see this show while it lasts. There sincerely may not be a more authentic and historical depiction of Chinese jazz culture anywhere else. Yet it would be unfair to speak of jazz in China only in relation to its heritage — one might wonder how different New York or Paris would be if their respective jazz scenes were void of innovation and limited to George Gershwin or Django Reinhardt tribute shows.

Where are the innovators in the present age?

At Tivoli, a freshly renovated bar at the edge of Changshou Park, an all-new jam session has just begun. It is unlike every other Shanghai jazz jam in one major way: on this evening, apart from me, all participants are Chinese. The musicians are young, and the audience is as well. Some are from Shanghai, others from as far as Xinjiang. The majority are male, but a few young ladies also make it onstage to show off soft, crooning vocals.

“Jazz is developing in China — all of us are starting jazz,” explains Zhang Shun 张顺, known as Panda, a youthful drummer who has been conscientious of jazz for only a few years. “Chinese people like pop and rock.” He imagines an average Chinese person’s response to jazz being, “What is this? I can’t understand!”

There was humor in his thoughts on the subject, but more obvious was his passion to begin a trend. He is firmly aware of the challenges he and his compatriots faced, from education to history.

“Music education in China is not good,” he says. “When I was a student, I didn’t know any instrument except for piano.” And students interacted very little with the instrument itself. “The teacher just played. Schools conveyed that music was not very important.” His school routinely canceled music class if something more important was impending in the week ahead — namely, testing. “If there is an exam this week, every other objective goes out.”

Panda mused on the legacy of Shanghai as one of the world’s first true jazz cities, recalling the days he read about when jazz was also China’s own.

“In one day, everything is cut,” he says, his grin disappearing.

The young players at Tivoli show intensity, glee, and skill, making me think there just might be a real movement to integrate jazz with Chinese culture. And then there are people like Simon Wu, a Shanghainese saxophonist and entrepreneur who has been active in the scene both in China and in Tokyo for over two decades, and was witnessed by this author belting a masterpiece of a solo last fall at Music China, one of Asia’s largest events in the music industry. He now manages the Simon Wu Saxophone Elite Club, which is hosting an event on April 21-22 at Huangshan Hotel in Pudong to celebrate the club’s one-year anniversary.

“Now, we’re starting the jazz rebirth in China,” Panda says.

Summarizing his culturally syncretic jam session, John Shanghai says, “At the end of the day, it’s to give another image of China.” What that image is, exactly, is hard to say, but maybe the point is it doesn’t need to be articulated. Much like rhythm, it has to be felt.

“I think it’s freedom,” Panda says about what he loves about jazz. “When I play something, I can play what I want. I didn’t obey something…I can open up my body. It’s very interesting. I don’t follow something. I just follow music and do what I want.”

Also see:

Sinica Podcast: David Moser and Jess Meider riff on jazz in China

The fate of music festivals in China’s current era of cultural nationalism