When China embraced classical music: The Philadelphia Orchestra’s historic 1973 tour

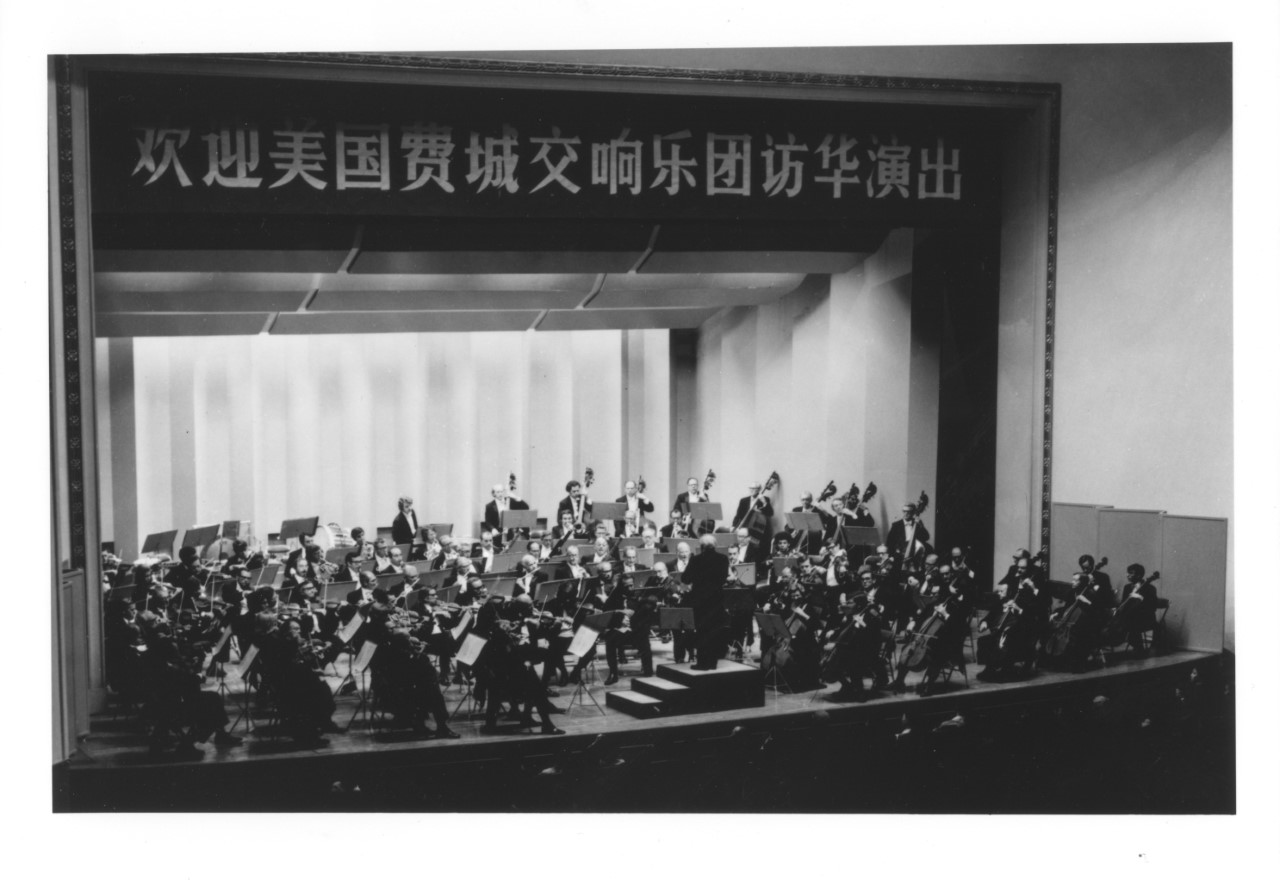

They put up with half-hearted crowds and a demanding Madame Mao. But those who went on the 1973 China tour with the Philadelphia Orchestra remember it as a monumental event — one whose lasting impact is evident in China’s embrace of Western classical music today.

This article originally appeared on China-US Focus

and is republished here, with minor edits, with permission.

All images are courtesy of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Sixteen-year-old Tan Dun 谭盾 worked in the rice fields in the Huangjin Commune in South Central China, following Chairman Mao’s edict that educated youth must be “re-educated.” One afternoon, he heard beautiful but strange music filtering across the fields from the village loudspeaker, a broadcast of the Philadelphia Orchestra playing in Bejing. The teenager paused in his work. The fact that the orchestra was in Beijing was unique. This was 1973: China had been closed to the world for almost a quarter century, and classical music had been banned for almost a decade. As Tan Dun listened, he vowed that he would follow his passion for music.

Tan kept that promise. In 2001, he received an Academy Award for his musical score for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Today, he has become one of a handful of highly respected composers in the world.

“You hear stories like that,” said Philadelphia Orchestra violinist Davyd Booth, who performed in that ’73 concert. “Sometimes you think, ‘Oh, the China trip is real great. This is my job.’ And then you suddenly realize that the thing that you’re doing and the experience that you have can affect people so incredibly strongly…deeply…in such a life-changing way.”

Since 1973, China has gone from having no Western music to being one of the greatest consumers of and contributors to the classical music world. Classical music, rather than being shunned, is considered a mark of an educated person. Orchestras and conservatories continue to pop up all over the country. Chinese musicians are treated with rock-star status. And now, the U.S. looks to China for help.

The evils of classical music

After World War II, China fell into a civil war that ended with the Nationalist Party fleeing to Taiwan and ceding power to Communist leader Mao Zedong. Chairman Mao closed China’s borders and would go on to initiate a series of campaigns, including the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), which demonized old traditions, wealthy people, intellectuals, those exposed to the West, and, among other things, classical music.

New York Philharmonic cellist Qiang Tu, whose father was the principal cellist for China’s Central Broadcasting Symphony, recalled: “For a while everything just stopped. [My father] was sent into the countryside to plant vegetables. No more classical music was played. No matter what kind of instrument you played, publicly you had to play Chinese music.”

“We were only allowed to practice the revolutionary Peking opera and ballet,” said musicologist Li Wei. “There were eight operas. They were composed with revolutionary content. So they were okay.”

While the Chinese government’s draconian policies made some people fearful, it made others hold on to their music tighter. When Qiang Tu’s father returned from the countryside, he enlisted the help of friends from a music factory to build young Qiang a cello. “I still remember all my father’s friends,” Tu said. “Every Wednesday when they had their break — the factory rests on Wednesdays — they all came on their bicycles to our small courtyard. They would start from morning [and work until] late afternoon, helping him make us the instrument.”

Tu would go on to become the first Chinese musician to join the New York Philharmonic.

“A lot of people practiced classical a little bit,” Li said. “I actually — when I practiced, I closed my windows, put my curtains on, and used the mute. I just didn’t want people to hear. If people heard, they probably would have blackmailed me or criticized me. So I don’t want that trouble. That was the Cultural Revolution.”

It was into this tense, fearful atmosphere that President Nixon entered in 1972. A year later, in an effort to cajole China’s doors open, Nixon arranged for a cultural exchange, which included not only the famous ping-pong match that lent its name to “ping-pong diplomacy,” but a visit from the Philadelphia Orchestra.

“Mrs. Mao was a really tiny lady, but everybody kowtowed to her. We had to borrow the music.” —Davyd Booth

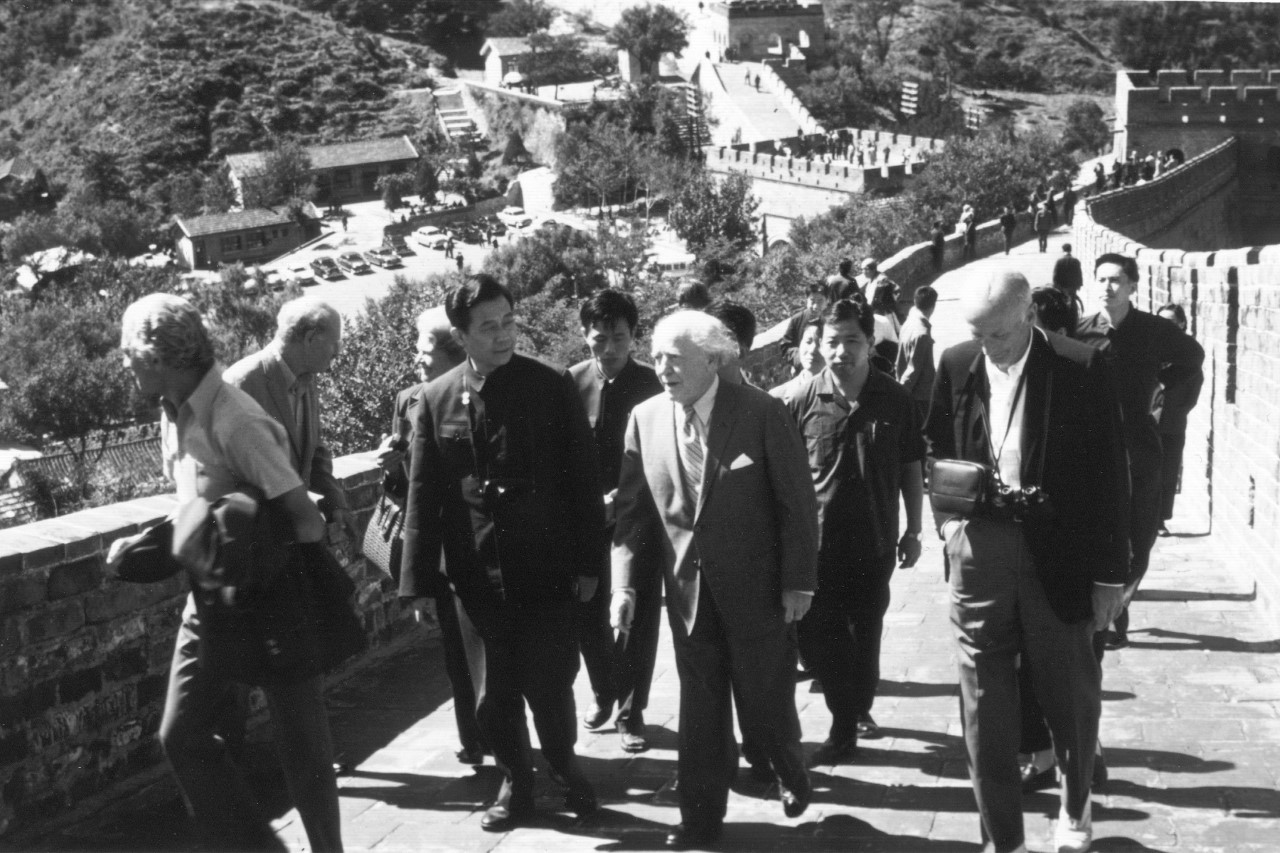

Violinist Davyd Booth remembered that trip to Beijing well. “Everyone’s hairstyle — whether they were male or female — was pretty much the same. They all dressed alike. There were very few buildings, especially no tall skyscrapers. [The city] was full of farmers. And…I never saw so many bicycles in my life. At certain times of the day, there would be nothing but this unbelievable sea of bicycles. It was so different at the time from anything you could possibly imagine.”

The performance was not without its hitches. Madame Mao — Jiang Qing 江青 — who was later sentenced to life in prison for her role in the deaths of tens of thousands of people — was in charge of the event. She decided at the last minute that she wanted the orchestra to play Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 — the Pastoral — rather than the Fifth Symphony, which was agreed upon after months of back-and-forth negotiating. Not only did Maestro Eugene Ormandy hate Beethoven’s Sixth, but they hadn’t brought the music.

“Mrs. Mao was a really tiny lady, but everybody kowtowed to her,” recalled Booth. “We had to borrow the music.”

This was not easy at the time. Madame Mao had her people scour far and wide for what turned out to be handwritten — and not totally accurately — scores. The musicians, familiar with the symphony, muddled through quite well. So, they were surprised by the audience’s lukewarm response.

“Ormandy got really upset and almost had a meltdown in his dressing room because of the applause,” said Booth. “Of course, everyone looked toward Mrs. Mao, and everybody’s reaction — it wasn’t that overwhelming.”

While the applause was tepid and tentative, the music forged an unbreakable bond. “You know, they make it sort of a hackneyed thing that ‘music is a great universal language,’” Booth said. “But it’s really true. You can play music, and you can develop friendships with people just through the music. [The ’73 concert tour] was an eye-opening experience for the Chinese. Now, China is one of the biggest markets for classical music. Ever since the ’73 thing, classical music has just — I mean, it’s been almost like a volcanic eruption.”

Crazy about classical

Today, the Chinese are both the greatest consumers and the most amazing contributors to classical music. Composers like Tan Dun and pianists like Lang Lang 郎朗 and Yuja Wang 王羽佳 are celebrated as superstars. Music once given tepid applause is now wildly embraced.

“There are so many orchestras in China in the past few years that have come up,” said San Francisco Symphony violinist Jay Liu. “And the government is behind them. Every small city has a new orchestra. Even in Tibet. Even in Inner Mongolia.”

“Today it’s considered a mark of prestige to have a symphony orchestra,” said Sheila Melvin, who has written two books on classical music in China, and whose husband, Dr. Jindong Cai, is one of the producers of the forthcoming film Beethoven in Beijing. “So they’re all over the country. There are over 70 orchestras now, and many of them started in the past five years.”

While the number of orchestras is small compared with that in the U.S., which has 1,200 symphony orchestras, American orchestras are dependent on an aging audience, donations, and philanthropic sponsors.

“One thing I always notice,” said Melvin, “is how young the audience [in China] is, which is kind of the exact opposite of what you notice when you go to a concert in the U.S. [In China,] there are lots of young people. It’s a hot date to go to a symphony together.”

Added another producer of Beethoven in Beijing, veteran Philadelphia Inquirer journalist Jennifer Lin: “There are scalpers outside the theater scalping tickets. That doesn’t happen with the Philadelphia Orchestra, I can tell you that.”

Cellist Qiang Tu weighed in, remembering his 2008 tour with the New York Philharmonic: “The people were really crazy with our performance. In the first half, we played Mozart’s Symphony No. 8, and the people were so overwhelmed that we had to come back to give the encore of the third movement…before the intermission.”

What has changed over the past 45 years? What has made the difference?

“Classical is very much alive in China largely because of the government,” Li Wei, the musicologist, said. “They sponsor it. They patronize it. They have a venue to display it. Right now, because China has a lot of money, they put a lot of money into it. They can even support Western symphony orchestras.”

In fact, the Philadelphia Orchestra is supported by China. Despite its reputation as one of the big five American orchestras and its history of entertaining audiences (for more than a hundred years), the Philadelphia Orchestra declared bankruptcy in 2011. It was China that came to the rescue.

“They basically said, ‘You come here every year,’” Wei said. “They provide everything, and basically pay a lot more than if the Philadelphia Orchestra were playing back in the United States.”

Money isn’t everything

Today in China, there is financial support from the government, venues to play in, enthusiastic audiences, and “an astounding number of people who are learning instruments,” said Lin, the journalist.

A fine example is that of pianist Lang Lang, who began studying when he was three.

Lang Lang had a “tiger dad,” who quit his job as a policeman and moved with Lang Lang to Beijing so that his son could be trained by the best. Lang Lang’s mom stayed back at her job as a telephone operator in Shenyang and sent them money to live on. According to musicologist Li, Lang Lang’s highly respected teacher told Lang Lang he had no talent and that she would not teach him anymore. “His father said, ‘Okay. So that’s it. There’s no hope for you. You can jump out the window.’”

Instead, after months of self-questioning — at age 9 — Lang Lang convinced his father to find him a new teacher. Several years later, they both emigrated to the U.S., where Lang Lang studied at the Curtis School of Music in Philadelphia. He is now one of the most respected pianists in the world.

“He’s a really fabulous, fabulous world-star pianist,” said the violinist Booth. “They say that the sale of pianos in China is practically the biggest in the world, and that literally — I’m not exaggerating when I say this — millions of people now take piano lessons hoping to become the next Lang Lang.”

The fact that Lang Lang’s Chinese teacher did not recognize his talent is dumbfounding. But, according to Li, it’s not that surprising: “China’s got an almost brutal education system. There’s always corruption and cheating going on. There’s all kinds of stories. If you want your child to pursue their professional career, if you want to eventually be admitted to (the top conservatories), you get to know the professors.”

Li said that young people not only took lessons from the conservatory professors — or their assistants — at exorbitant rates, but these children took lessons to prepare for the lessons. He said many parents are beginning to think this system — reliant on whom one knows and how big one’s “red packet” is — is not worth it.

“I think parents generally realize, ‘I would rather spend this money, invest this money in the U.S. or other countries,’” Li said.

In addition, China still has censorship, which stifles creativity. “There’s a lot of government interference,” Li said. “You have to write something that has zheng neng liang 正能量 — or ‘positive energy.’ You’re supposed to glorify the Chinese Communist Party. You cannot freely write your music.”

A reciprocal relationship thrives

In the past half-century, the U.S. and China have developed a reciprocal relationship with regards to classical music. China provides enthusiasm and funding, and the U.S. offers talented musicians and the uninhibited/uncensored freedom to create.

“There’s a back-and-forth thing,” said Booth, who since ’73 has toured with the orchestra in China 10 times, and each time is offered a hero’s welcome. “It is light years beyond just the relationship of going there and playing concerts.”

The artistic adviser to the Philadelphia Orchestra recently demonstrated this. Remember that teenager Tan Dun, who listened to that ’73 concert in the fields? He went on to study not only at the Central Conservatory in Beijing, but also at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. He not only has had an illustrious career as a composer (receiving that Academy Award), but also has served as the artistic adviser for the 2014 Tour of Asia. That year, he created Nushu: The Secret Songs of Women, a 13-movement work for video, solo harp, and orchestra. The work captured the sounds of Nushu 女书 script, a secret writing system (literally meaning “women’s script”) devised by women in central China who had been disallowed formal education and disallowed a voice. Adviser Tan Dun debuted the piece with the orchestra, first in Philadelphia, then in Beijing — and then in his hometown of Hunan Province.

“It was a very emotional moment,” said Lin. “It shows how the relationship has evolved.”

The ’73 Philadelphia Orchestra tour stoked long-dormant embers in the hearts of the Chinese, sparking over the past 45 years a wildfire of classical music appreciation. Once closed to Western music, contemporary China not only excels at teaching and performing the classics, but also works with the U.S. to keep American orchestras alive. In turn, the U.S. provides the nurturing, creative climate for Chinese musicians to continue thriving. What began as a one-off moment of cultural exchange has turned into a long-term reciprocal bond between the U.S. and China, a bond from which the whole world benefits.