NBA takes spotlight in China, offers valuable lesson for country’s sports industry

The China Sports Column is a The China Project weekly feature in which China Sports Insider Mark Dreyer looks at the week that was in the China sports world.

China usually likes to do things its own way, or at least localize a successful global concept. After all, the phrase “…with Chinese characteristics” is a cliche for a reason. But when it comes to sports, sometimes the authorities just can’t make up their minds over which side of the fence they’d like to be on.

Is it better to replicate foreign success with a few minor tweaks, or build a Chinese version from the ground up (or, more accurately, from the top down)?

A couple of storylines this week from the country’s two most popular sports — soccer and basketball — illustrate the difference and sum up where the Chinese sports industry currently sits.

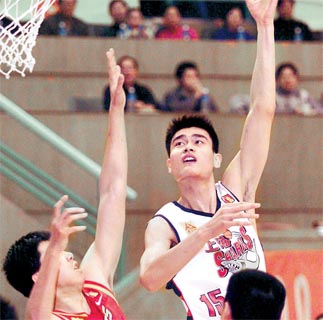

The NBA stands alone in China as a powerhouse, unchallenged by other international basketball leagues and unmatched by China’s domestic rival, the CBA. True, the CBA has had its moments — most notably when the recently retired Stephon Marbury endeared himself not just to Beijing fans, but to basketball fans around the country by embracing China on and off the court. But it’s a measure of where the CBA sees itself — and where it wants to be — that association head Yao Ming has attempted to introduce several NBA-style improvements, both on the playing side as well as to the league’s commercial set-up, since he was appointed to lead the CBA 18 months ago.

But for all of Yao’s progressive moves — and the plaudits he’s won during his short tenure — entrenched interests still pose considerable resistance to change. There might come a day when the CBA truly rivals the NBA for the affection of Chinese sports fans, but that day is a long, long way off.

That point was rammed home once again on Friday when the Philadelphia 76ers and the Dallas Mavericks faced off in Shanghai for the 25th China game in league history, a matchup that has been highly anticipated since it was announced in April. It may have only been a preseason tune-up for the players, but try telling that to the fans who lined up outside the team hotels earlier in the week to greet their heroes —

— or to the packed house at the Mercedes-Benz Arena, which cheered every basket and stayed fully engaged until the very end.

And why wouldn’t they like it, with much-hyped Dallas rookie Luka Dončić making lob passes like this:

The 76ers’ J.J. Redick also put on a show, scoring 28 points without missing a shot — 10 for 10 from the field, including 7 for 7 from three-point range. You might remember Redick issued a truly baffling Chinese New Year’s greeting in February — it involved a racial slur! — and it turns out the Chinese fans remembered, too: they half-heartedly booed his introduction. But it seems like it’s all water under the bridge now, because here’s what Redick had to say after the game:

“It was the most polite booing that I’ve ever received in my life,” Redick said. “I mean, they booed and they cheered. It was like, ‘We’re mad at you, but we appreciate the way you shoot a basketball.'”

The only discernible difference between the gameday experience in Shanghai and one back in the U.S. was that Chinese fans were arguably more passionate — this was, after all, their once-a-year chance to see their idols perform in the flesh.

The same teams will play again in Shenzhen on Monday, and the devotion will no doubt be similar. Star power sells in China, and the shortened rosters in basketball compared with most other team sports means that each star burns ever brighter. Only the very top European soccer players can rival the NBA stars in terms of adoration, but, crucially, they are spread out over a whole continent’s worth of leagues.

The NBA has long set the gold standard for sports leagues in China — a top quality product on and off the court with legions of loyal fans. The Chinese Super League also has loyal fans — but, unfortunately, that’s where the similarities end.

Admittedly, the league has made enormous strides in recent years — remember that 33 players and officials were given lengthy bans and even jail sentences for match fixing as recently as 2013 — but just as those on the pitch appear to have stopped breaking the rules, those off the pitch keep changing them.

Take the CSL’s Under 23 rule, which states that teams can play up to three foreign players in a match, but only if three U23 Chinese players also feature. The implementation of the ruling remains open to abuse, with teams able to play their foreign stars for the whole game, while subbing the youngsters on for a just a few minutes.

But things have become even worse.

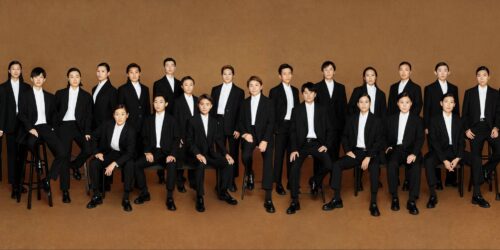

Toward the end of this season, teams were informed that they didn’t have to play the required number of U23 players if they had lost any of their young players to national team call-ups. This week, 55 Under-25 players were summoned to a two-month training camp at short notice, meaning that they’ll miss the final six games of the season.

Imagine how French champions PSG would react, for example, if 19-year-old Kylian Mbappé — voted Best Young Player at this year’s World Cup — was declared unavailable for selection for two months. Clubs would be in uproar, even if they had been given fair warning.

But in China, things are just done differently.

Every team in the league knows that country trumps club — the opposite of how things are done in Europe — and so there’s little point in arguing when the CFA issues another edict, however idiotic it might be. China’s stated goal, after all, is to become a soccer superpower, and that starts with the national team.

But you’d be hard pushed to find a football expert tell you that 55 young(ish) players would be better served by being holed up in a military-style training camp than back playing first-team football at their respective clubs. China needs all the help it can get — especially with regards to the development of its young players — but the CFA’s random rules have placed yet another obstacle in their way.

Off the pitch, there is a clash of cultures, too.

Beijing Guoan is currently in a dispute with the CSL over its league-wide deal that allows Nike to produce jerseys for all 16 teams, instead of allowing each club to negotiate with their manufacturer of choice, as happens in Europe.

With the CSL’s transfer tax slapped on every club that runs at a financial loss — the intentions of which are admittedly honorable — it then becomes ludicrous that clubs are not allowed to maximize their own revenue streams through perfectly legitimate channels.

Versions of this battle that can be found all over Chinese sports. Li Na 李娜 was famously allowed to split from the country’s state-run system, choosing her own coaches and playing schedule, while signing commercial deals of her choice.

But when star swimmer Sun Yang 孙杨 — among others — tried something similar, he was promptly smacked down by the federation, and an uneasy truce remains to this day.

For those in the sports industry, there is universal agreement: China needs to modernize across all levels, even if that means turning to — whisper it quietly — commercial principles. Healthy, sustainable finances away from the playing field breed sporting success. But, in some sports, those in charge remain determined to place roadblocks in the way.

In 2015, China pledged to create the world’s largest sports industry by 2025, worth 5 trillion RMB, or about $800 billion. It’s a statistic that’s wheeled out at every sports conference around the world. But unless China genuinely embraces some commercial principles, the sports industry is in danger of simply running itself into the ground.

The China Sports Column runs every Friday on The China Project. Follow Mark Dreyer @DreyerChina.