Writing from In-Between: A Conversation with Yan Ge

Yan Ge 颜歌 has lived much of her adult life in steamy, landlocked Chengdu. When she moved to Ireland with her husband in 2015, she struggled with the notorious Irish weather. Winter kicked in at the tail of September with pouring rain; once the rain ceased, a biting coldness lingered in the air. And the unrelenting wind? She simply didn’t know what to do when it struck. No wonder people gravitated toward drinking establishments.

Born in 1984 to a family of intellectuals in Pixian 郫县 (píxiàn), a historical town in Chengdu known for its spicy, flavorful chilli bean paste, Yan won the first prize in a national writing contest at the age of 18, and began steadily publishing one to two titles a year. Her early novels, such as Tales of Extraordinary Beasts 异兽志 (yì shòu zhì) and May Queen 五月女王 (wǔyuè nǚwáng), draw inspirations from ancient Chinese myths and are marked by their exquisite prose and out-of-this-world imagination. Over the years, they have garnered her a large fan base.

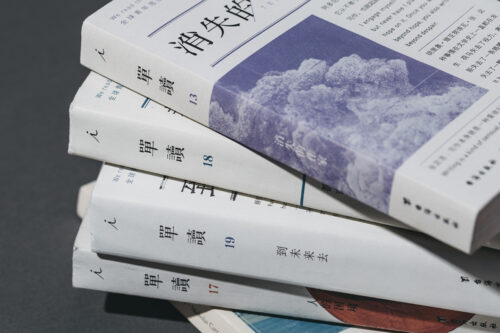

But she isn’t someone who lingers at one place for long. In 2011, realizing that as a writer, she was doing too well in her city, Yan went to Duke University in North Carolina as a visiting scholar. It was there, the place probably farthest from her hometown, that she wrote her best novel to date, The Chilli Bean Paste Clan (我们家 [wǒmen jiā], literally translated as “Our Family”). In 2012, People’s Literature magazine named her as one of the top 20 future literature masters in China, a recognition equivalent of The New Yorker’s “20 under 40.”

After coming back from the U.S., Yan met her future Irish husband in Chengdu, and the two got married a year later. In another effort to get out of her comfort zone, Yan applied to Columbia University’s MFA program and was admitted. However, when she tried to convince Daniel, who is also working on a novel, to move to New York with her, the Mayo-bred former crime reporter, whose literary sensibility echoes with hers in many ways, said to her: “Up until this point you’ve experienced China and America. Both are big countries with massive cultural bodies. You should come to Ireland as a trial to experience something different.” He believed it would benefit her as a writer.

Yan found it hard to say no. After a book tour for her newly published short story collection, Sad Stories of Pingle Township 平乐镇伤心故事集 (pínglè zhèn shāngxīn gùshì jí), Yan said goodbye to family and friends and embarked on a new journey. Thus, “a Chinese literary sensation moved to Ireland,” as described by The Irish Times.

When I visited Yan in Dublin in 2015, she brought me to the watering hole where her husband used to kill time after work. People with varying degrees of drunkenness were scattered in different corners of the crowded pub, downing tall glasses of Guinness. Yan ordered for us two mugs of hot toddy. In no time, our steaming drinks drew the attention of a rosy-cheeked young man from one of the crowds.

I was a little uneasy as he strode toward us. Despite the throngs of international tourists that flock to the literary city, I frequently find myself the only Asian face in Dublin. In fact, a moment earlier, Yan had echoed my observation and the heightened sense of self-consciousness. But, to my surprise, she quickly brought the young man into her rhythm, evading his slightly personal questions and returning his curiosity with witty questions, and sent him away in a cordial mood.

In my recent conversation with Yan, I saw with more clarity what a superb conversationalist she was. Although she confesses to having the feeling of “role-playing” when talking to natives about local politics, in my opinion, it is exactly her capacity to play roles, however difficult it might be, that enabled her to create one of the most original characters in contemporary Chinese literature — Xue Shengqiang 薛胜强, the (anti-)hero of The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, translated into English by Nicky Harman and released in the U.S. earlier this May.

The head of a thriving chilli bean paste factory in southwest Sichuan, Xue is a middle-aged, foul-mouthed misogynist with a huge appetite for women and liquor and spicy food. To honor his mother’s contribution to the family business and promote the factory, Xue agrees to hold a grand party for the matriarch’s 80th birthday. Hot on the heels of this decision, his family members, with whom he has grown apart, return to Pingle Town, stirring up old rancor and bittersweet memories. As the date approaches, everyone begins to give Xue a headache: his wife finds out about his mistress, his elder brother is all mysterious about his doings in town, and his manipulative mother constantly outwits him. As the celebration reaches its culmination, secrets, old and new, finally surface and explode.

Brimming with descriptions of spicy, tingling, numbing delicacies emblematic of Sichuan cuisine, the story speaks to one in the darkly innocent voice of Xue’s daughter and is told predominantly in the unabashed, laid-back, yet subversive Sichuanese. Now, does it surprise you that Yan seldom eats spicy food and speaks to me, a fellow Chengduese, in impeccable Mandarin?

After she moved to Dublin, Yan encountered Jhumpa Lahiri’s essay “Teach Yourself Italian” on The New Yorker and shared a quote on Weibo: “It’s not possible to become another writer, but it might be possible to become two.” She made it clear from the start that she wouldn’t be one of those diaspora writers who writes in Chinese or writes in English about a China they remember. Having ruled out these two possibilities, she found herself truly on a road less traveled. Since 2017, she has published two short stories, “The Writer Who Lives in a Suitcase” and “Looking for the Japanese,” in The Irish Times. Shortly before I reached out to her for this interview, her latest short story written in English had been selected into Faber & Faber’s anthology of New Irish Writers, due for publication next year. Yan tweeted that it felt “surreal” to be recognized as an Irish writer.

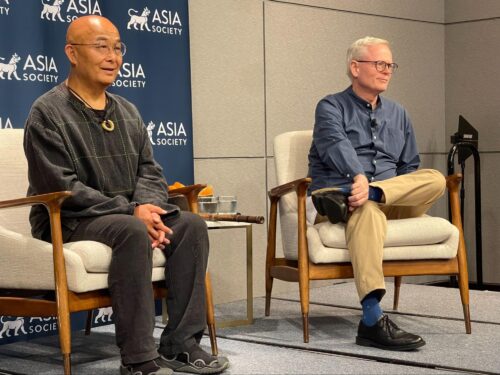

In August, taking an hour off her busy schedule as a young mother, Yan discussed with me the complexities and nuances of writing in one’s second language, the challenges she and Harman encountered when translating The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, and the shape she has in mind for her future work.

(Some answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.)

Yan Ge: It feels nice, speaking to you in Chinese.

The China Project: I guess these days you don’t have many opportunities to speak in Chinese.

Yan Ge: Very little. It gives one a rather rootless feeling. I mumble a sentence or two in Chinese to my laptop when I’m working on my new novel, which is in Chinese. I wonder if I’m having a crisis. Before (moving to Ireland), it didn’t occur to me that this would be so difficult — not that writing in English is difficult, but it has caused some confusion. I used to think it kind of fun to write in English, to have a new experience. But now I feel as if uprooting myself from Chinese has enfeebled me. Sometimes it saddens me to think that the Yan Ge who speaks, reads, and publishes in Chinese feels almost like my previous incarnation. When you switch language, your personality, or persona, will undergo a slight, or probably profound, change.

I found it easier to breathe when I was in the UK, where you get a sense that those writers, coming from various cultural backgrounds, simply choose to write in English because it’s a common language for communication. But in Ireland, I get the feeling that I’m speaking their language. In daily life, obviously you talk to other people about things happening in Ireland — it’s not a matter of difficulties of communication, but of participating in a different discourse, such as conversations about their local politicians. Of course I can talk about it, but the person who’s talking isn’t me; sometimes I felt like I was role-playing.

“I feel as if uprooting myself from Chinese has enfeebled me.”

I’m still working on this novel, I’ve been working on it for four, five years. I really want to finish it, but I don’t have enough time, and to some extent, I’m getting further and further away from the writer who started this book and her aesthetics. Of course it could be just a matter of warming up to gain momentum. If I work on it intensively for some time, I can get back on track. But even if I did, it would feel like a dream to me. Besides, I need a big chunk of time, which has become a luxury since my son was born. Now I write mostly in English, nonfiction pieces and short stories. Writing in a new voice and about things happening here is a less melancholy experience; it’s present, fun, and quite uplifting.

The China Project: Do you think having a child and taking care of a family prevents female writers from producing novels, to some extent?

Yan Ge: I think it depends. For now, having to take care of a very small child is a destructive blow to my writing. But I don’t think one should give up having a child just to have more time to write. Personally, as a human being, I don’t think it makes sense to sever myself from such an experience for this reason. When I was pregnant, I met Anne Enright at a party. She told me that before she had her first child, her agent said to her, If you want to become a writer, then you shouldn’t have children. Anne ended up having two kids and she said all of her best works were written after she had her children, including The Gathering, which won her the Booker Prize. She said even now there are people who will say, She could have done better if she didn’t have the child. And she said, What does that mean? Do I have to win a Nobel prize to be successful enough?

I think it’s absolutely okay if a woman chooses not to have a child if she doesn’t want to. But I’m not like that. What’s more, it seems to me fundamentally wrong to give up motherhood for writing. It doesn’t do justice to writing, either. So I decided to confront the hardship.

I’m feeling like the “Lincoln in the Bardo”; not Lincoln, but “in the Bardo.” I find myself in an in-between state: I’m leaving a place for somewhere else; I’m not there yet, I don’t know whether I will arrive there, and this feeling is very difficult to articulate. It’s a very ambiguous and painful state.

The China Project: For me, the tug-of-war between two languages registers itself as an embarrassing amount of grammar mistakes.

Yan Ge: I don’t think it’s a linguistic problem. It’s about one’s state of mind. Even if I’m writing in Chinese only, I can’t work simultaneously on a crime novel and a children’s book. A while ago, I was trying to write in English and Chinese at the same time, and it was like climbing two mountains. You exhaust yourself climbing all the way up to the top of one mountain, dig a barrel of earth there, then you have to get down and climb to the top of the other. It’s completely okay to speak in two languages in your daily life. But when it comes to creative writing, I find it wise to separate your projects. Better to concentrate on one project this month, and then shift to the next one.

It used to bother me a lot, partly because I had no reference, no model who could really inspire me. But a while ago, I went to Sweden for a literary event, and it turned out to be very inspiring. I realized that for many European writers, who come from Germany, Austria, Sweden, it’s very normal not to write in their mother tongues. Chinese is a very self-sufficient language spoken by a large population, so to us, abandoning Chinese is a big thing. But when I was speaking to a Swedish writer, who comes from an Eastern European country near Serbia, whose mother tongue isn’t Swedish, he told me there are also Turkish writers in Sweden who write in Swedish, and nobody think it’s a big deal. I found this fascinating. Another literary critic introduced me to Yoko Tawada, a Japanese writer who lives in Germany and writes in both Japanese and German. I realized that it wasn’t a big deal not to write in one’s mother tongue, at least for European writers. The clashes of different cultures and experiences have become a most normal thing to them. This discovery gave me a boost.

I was reading David Szalay’s All That Man Is. He was born in Canada, grew up in the UK, and lives in Budapest. He’s a pretty British writer, but the story is about nine men whose ages range from eighteen to eighty, with a fixed age gap between one another. They are scattered in different European countries: the UK, Cresia, Finland, France. This is, in my reference, the first European novel I’ve ever read. When I was living in the U.S. and reading Jonathan Franzen, his novel struck me as a very American novel. For a long time, all the American writers you can think of, including many writers in the UK, such as Ian McEwan, they are writing the kind of English novels one can imagine. David Szalay is a very British writer, but he’s written a very unusual book. I remember there’s a chapter about a tabloid reporter in Denmark, who’s following I-forgot-which country’s agriculture minister. When asked how he managed to capture a Danish tabloid reporter with such vividness, did he have any related experience? He said no he didn’t, he just made up the whole thing. Reading his novel inspired me a lot and showed me a new path. This is a very European novel, with different cultures, experiences, ways of living entering and exiting the stage, providing a unique slice of the world. Although English is a language used by American or British writers, the world it expresses can still be very rich. I love this about Europe.

The China Project: Is Europe more likely to produce “world citizen?”

Yan Ge: I agree. When I visited Europe for the first time to attend a literary festival, I felt the same. Back then I was studying at Duke University in the States. Although you could meet all kinds of people at the university, these people were deeply rooted in the mainstream American culture, functioning under a set of shared principles. They might look different from each other, but they were all very “American.” I went to the Netherlands with four writers from Iran, the Netherlands, Czech, and Egypt. A few years ago the Egyption novelist was sued by a reader for explicit descriptions in his novel and judged guilty by the court. What I’m trying to say is that in Europe, you get to meet all sorts of people, we communicate in English, but we operate in different ways, act as different individuals from different cultural backgrounds, we don’t follow certain principles or norms, we don’t pretend that we’re Americans or British. There is no “classic”; you don’t have to copy any classic or standard.

“I won’t write a ‘Chinese’ story. If I want to write one that happens in Pingle Town, I might as well write it in Chinese, that way it’s more satisfying for me.”

I remember there was a Chinese woman studying creative writing in the U.S. who once got feedback from her professor that “this is not Chinese enough.” Such comments drive one crazy. When I was writing for magazines in Ireland or the UK, no one asked me to write a “Chinese” story, nor have I written about China a lot. The short story I recently wrote has been selected by Faber & Faber into their collection of New Irish Writing, due for publication next year. Every year they choose 22 top Irish writers based on their latest, unpublished work. I wrote a story set in Dublin about an Irish man. The narrator is a Chinese girl who grew up in Ireland. This is a Dublin story, rather than a Chinese story. The editors quite liked it. They didn’t expect me to write a Chinese story, and they wouldn’t say this was not Chinese enough, because I didn’t write about China; I wrote about Dublin. I think this is probably where Europe differs from the U.S. I’ll surely write stories with Chinese perspectives, Chinese characters, and Chinese elements; this is unavoidable, and there’s no need to avoid that. But I won’t write a “Chinese” story. If I want to write one that happens in Pingle Town, I might as well write it in Chinese, that way it’s more satisfying for me. But if I want to write a Dublin story, I can only write it in English, because I don’t know how to write it in Chinese.

The China Project: It depends on the language in which you’ve stored your experience.

Yan Ge: Exactly. If I want to write about my current life, thoughts about literature, or reflections, I can only write about them in English instead of Chinese. This is part of the reason I made up my mind to write in English. Because they can’t be expressed in Chinese. I definitely wouldn’t write in English about something I could write about in Chinese.

The China Project: And the readers are different, too. Readers from other countries have completely different cultural references and knowledge.

Yan Ge: That’s right. I think the biggest challenge of writing in a new language is not the change of language, but the change of readership. When you start to write in a different language, the implied reader you’re trying to win is different. It’s kind of tricky to write in English for readers who’re not Chinese. Tricky, but also fun. I was told that many writers would encounter writer’s block once they’ve explored every aspects of their experience. I realize that I’ve used up my Pingle Town experience. Once I finish the novel I’m working on, I can’t think of anything to write about — partly because I no longer live there. But I’m glad to have the opportunity to become a new writer.

The China Project: I guess the focus of your writing and your concerns will be different, too. Your Chinese works have a strong local flavor. Is this something you want to continue exploring in your English works, or are you interested in something else?

Yan Ge: I don’t have a big project right now and write mostly short pieces, but I want to explore meta-fiction, or literary fiction. I’ve always been interested in it. I want to write in the vein of the so-called “intellectual fiction.” Like Don DeLillo’s work, novels about novel as a literary fabrication. It will be different from my Chinese novels, which are set in rural and suburban towns and written in a more traditionally realistic way. It will be…

The China Project: A bit high-brow?

Yan Ge: Not necessarily, but it’s to play with ideas and sometimes even language and different experiences. I’ve finished a few short stories, none of which I can write in Chinese. It’s a pity that as a Chinese writer, at least as of now, I have been trapped by my labels: I’m this kind of writer, who’s interested in this kind of thing. I often describe myself as a rascal who does all sorts of experiments when she enters a new room. Besides, as a non-native speaker, I can try many things, even with the language itself. I think people tolerate this better than they do with native speakers. English is a slutty language, very tolerant, dynamic, and constantly absorbing new things.

“English is a slutty language, very tolerant, dynamic, and constantly absorbing new things.”

The China Project: I feel there’s an interaction between a work and the literary tradition in the language it is written. Chinese literature seems to favor a kind of traditional realism, or it has a rather narrow definition of “realism.”

Yan Ge: The influence of Russian, Soviet literature.

The China Project: Right! Something interesting happened to me the other day. I was preparing for an interview with another writer, whose novel has been translated into English and Chinese. I read both versions, but for some reason, I simply couldn’t finish the Chinese translation. I guess it’s because the Chinese translation failed to evoke a conversation with the Chinese literary tradition, or vice versa; whereas the English translation found a better audience in the English literary tradition.

Yan Ge: I haven’t read a Chinese novel for years. I read Chinese translations of Japanese novels. Japan and China have lots of shared cultural contexts; we evoke the same connotation when we speak of the moon. For me, the Chinese translation of a Japanese work is usually better than its English translation. The translator is not to blame. Take the English translation of my book as an example: I realized that many sentences, when they’re turned into English, become useless. Of course, Nicky (Harman) couldn’t just cut them out, she had to translate them. It’s a pity that when the audience changes, the joke is lost.

I’ve observed that in every culture, writers more deeply rooted in that culture are more difficult to translate. For example, the Irish writers that are very popular in China might not be as popular in Ireland, and vice versa. Kevin Barry, for instance. I can’t read his novels, they’re written in local dialect. City of Bohane is basically written in the Limerick dialect. I can read a little Scottish, aided by some sort of dictionary, but Kevin Barry’s book is about the place, there’s something beyond my grasp, not only linguistically, but also culturally.

The China Project: Sometimes as readers of local literature, when we are too immersed in our culture, we risk missing the hidden messages. Do you think translation, through uprooting a story out of its mother soil, can help elucidate its theme?

Yan Ge: I think it’s possible. Nicky is a very conscientious translator who never stopped asking until she found the answer. When I wrote in Chinese, if I was writing about a person who pretends to like someone he doesn’t, I would never point it out, nor would I remind the reader. There’s one section in the novel where Xue Shengqiang is planning his mother’s funeral in advance. Nicky’s first draft made me feel like Xue was very sad, so I told her, He actually wants her to die at that moment. He wants it to happen but he can’t admit it to himself — the joy he feels is too horrifying, even he himself wouldn’t acknowledge it. I do think translation can clarify the text. Sometimes I wonder whether I am too subtle as a writer — I think I’m being very obvious, while readers are left in a fog. I think I have to write indirectly, to leave room for guessing. But when Nicky was translating the novel, I explained to her all the hidden messages. In this sense, I think we’ve done a good job representing the characters and the dynamics.

The China Project: When The Chilli Bean Paste Clan was published in China in 2013, some critics praised its moral ambiguity. I wonder whether this ambiguity partly results from your subtlety as a writer. What did you think of Xue when you were writing the book? Do you want the readers to sympathize with him or pass moral judgement on him?

Yan Ge: When I began to write this story, I was very angry. I could feel my anger when I reread it. The other day, a lot of people were talking about the #MeToo movement in China and I felt deeply about it. I wrote this book because, as a young female writer, I have encountered many, many men who have behaved in such an ugly way. I can think of many scenarios in my early twenties where, as a writer, I was thrilled — this was great material, it revealed the richness, the unspeakable darkness of human nature — but as a woman, I was absolutely traumatized. People often are surprised that this book is written by a woman. Actually, this book is a traumatized woman wanting to get back at those men by writing a story like this. It is venting, an expression of my anger, a therapeutic experience.

“This book is a traumatized woman wanting to get back at those men by writing a story like this. It is venting, an expression of my anger, a therapeutic experience.”

At first I was very angry. But it is important not to hold any moral judgement when you’re writing a novel. When I was writing this book, I passed no judgements on my characters, and I was actually surprised to feel the anger when I reread it. But I think my anger vanished as I wrote on. In the end I truly liked Xue Shengqiang. He is a misogynist, but once you get over it, you can see the other sides of him, his loyalty to his family and friends, his cowardice and kindness. In the end, I reconciled with him.

At first I was very angry. But it is important not to hold any moral judgement when you’re writing a novel. When I was writing this book, I passed no judgements on my characters, and I was actually surprised to feel the anger when I reread it. But I think my anger vanished as I wrote on. In the end I truly liked Xue Shengqiang. He is a misogynist, but once you get over it, you can see the other sides of him, his loyalty to his family and friends, his cowardice and kindness. In the end, I reconciled with him.

Xue Shengqiang was very easy to write, always full of energy. He came to me; it’s quite fortunate for me as a writer. Writing about him cured me. Besides, you can separate his behaviors from his personality. The way he speaks and makes friends is different from the way he treats women, and I spent more time on his characterization. The way he dates and thinks about women can be considered “events.” A friend of mine once said that Yan Ge doesn’t know how to write about love and romantic relationships. You’ll find that I’d quickly skip these things and focus on the daily life. Ultimately, this book isn’t about how he met his mistress, but how he gets along with his mother. Family dynamics instead of love and lust. I think I was able to find a way to treat the subject matter by avoiding a lot of stuff that I wasn’t really familiar with or couldn’t write about convincingly. It’s like I have drawn the legs of a table, and the readers say, Look, she’s drawn a table!

The China Project: The story is structured around the grandmother’s birthday party, but the storytelling smoothly weaves in and out of the present. English is a language that’s very precise with time. Have you and Nicky encountered any problems in the treatment of time? What were the solutions?

Yan Ge: Most of our energy was spent on translating all the dirty words. I don’t think we bothered much with time. There’re a lot of interior events, reminiscences. I like the uncertainty of time. At various points Xue would recollect when this thing or that thing happened; for me, it serves as a reminder to the reader that everything is tinted by his perspective, the uncertainty of his memories. In the end, particularly, everyone in the story comes to the narrator and tells her their side of the story, and you can see that people see things differently — Xue Shengqiang and his elder brother actually have opposite opinions about the same event. It appeals to me that our memories, our perception of things, are actually very subjective. Therefore, there is a haze enveloping the whole narrative. I tried my best to create such uncertainties.

The China Project: What would you say plays a vital part in holding the whole narrative together? Any techniques you were consciously employing? Did it have anything to do with your understanding of time and how an unreliable narrator tells a story?

Yan Ge: Not really. Let me tell you this: before I wrote The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, I was obsessed with structure. I wouldn’t start a story until I had a structure in mind. I preferred the symmetrical structure, all of my early novels are very symmetrical. After I finished Sound Orchestras (声音乐团 shēngyīn yuètuán), I completely broke down. I made up my mind — I’m done with structure. When I was writing The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, I told myself, Just follow your heart. I made no attempt to achieve any kind of structure. The book turned out to be very uninhibited and very short. With Sound Orchestras, I even made drawings; with this book, I wrote it in a freestyle way, and the whole thing is held together by Xue Shengqiang. He’s strong, powerful, and drags me to write about many, many things.