Our weekly explainer series, China Ties, looks at China’s relationship with different countries of the world.

It’s the latest round in a never-ending spat. In early August, the Chinese coast guard turned a water cannon on a Philippine ship ferrying supplies to the Sierra Madre, a rusty battleship deliberately run aground by the Philippine government in 1999 to stake its claim in the contested South China Sea (or West Philippine Sea, as the Philippine government has called it since 2011). China responded by demanding the Philippines remove the grounded ship from its territorial waters; the Philippines refused.

The Philippines is one of the most vocal states protesting China’s claims to the South China Sea, even taking it to court in 2013. It’s a sore point in what would otherwise be a prosperous relationship. Only this January, current president Ferdinand Marcos Jr. visited Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 in Beijing, both promising to increase an already booming bilateral trade, signing MoUs and deals for Philippine infrastructure projects, all while “emphasizing that disputes in the South China Sea are not the whole of bilateral relations.”

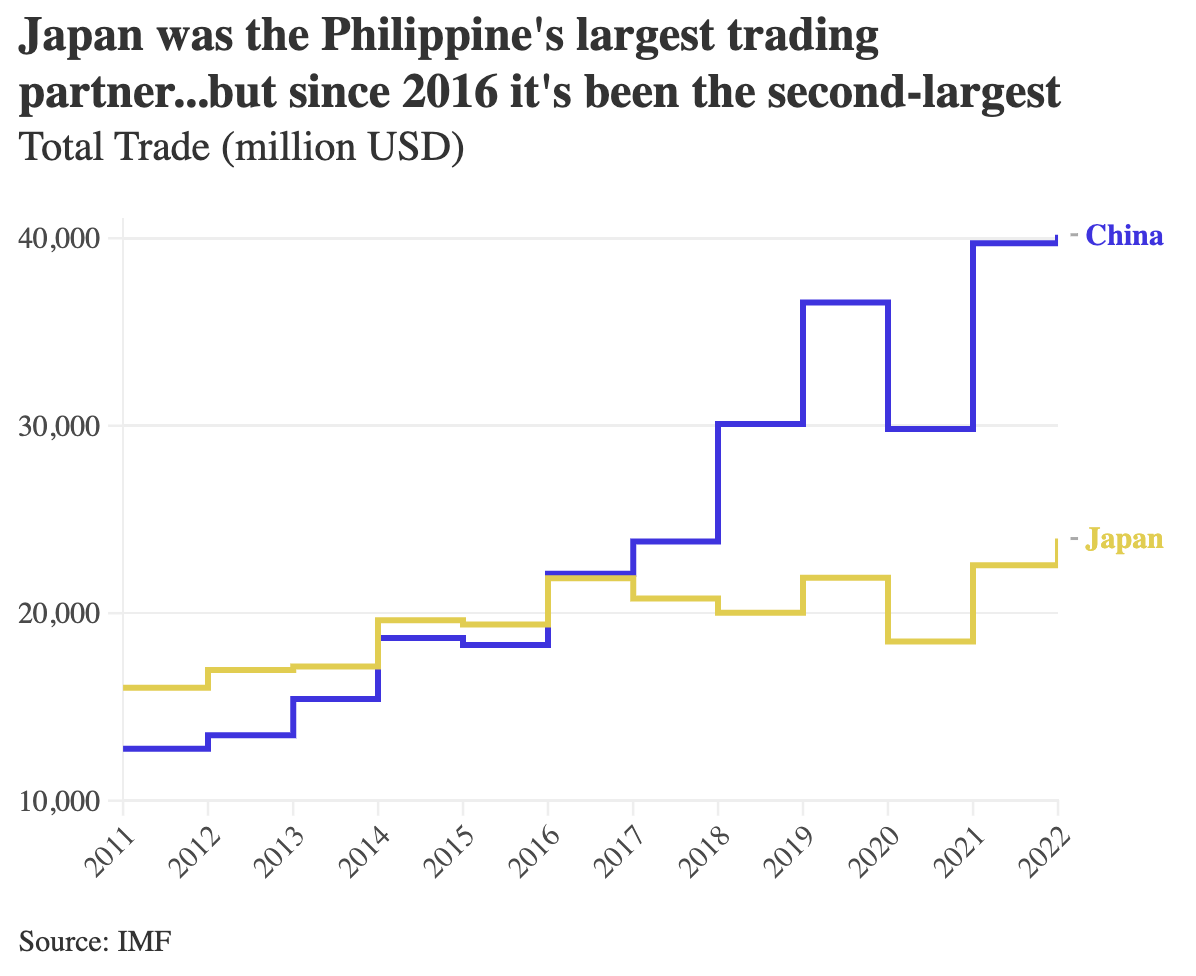

But it’s hard to keep the disputes from setting the tone. “China, my friend, how politely can I put it? Let me see… O… GET THE F*** OUT,” then Philippine foreign minister Teodoro Locsin tweeted in 2021 — now appointed by Marcos as his special envoy to Beijing after this most recent skirmish. A bold message to the country that’s been its largest trading partner since 2016.

Republic of the Philippines

Founded: July 4, 1946

Population: 117.3 million

Government: Constitutional Democracy

Capital: Manila

Largest City: Quezon City

Established relations with the P.R.C.: June 9, 1975

The two have partnered since 1975 — the warming relations between the P.R.C. and the U.S. aiding the diplomatic switch from Taiwan, along with the hope that Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 would stop P.R.C. support for terrorists linked to the Communist Party of the Philippines. But at that time, the Philippine government was desperate to boost its economy, and toyed with swapping back diplomatic relations to the wealthier Taiwan in the late 1980s and 1990s.

But the P.R.C. started to offer economic returns for its decision to stay — total trade rising to $4 billion from 1993 to 2003, promising infrastructure projects and a plethora of (small) aid donations for the typhoons, floods, and earthquakes that have hit the archipelago over the decades.

Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency (2016 to 2022) was about getting closer to China. “I need China, more than anybody else at this time,” he said in 2018, citing the need for Chinese money to fund his Build, Build, Build infrastructure campaign (the majority of projects now listed with China are around the city Duterte was once the mayor of). His tenure also included an increase in trade — China becoming the Philippines’s biggest trading partner in 2016, the year Duterte was elected — signing the Philippines up for the BRI in 2017 and backing China in the UN in 2019 over its mass internment of Uyghers in Xinjiang.

As with other BRI projects around the world, some of those begun under Duterte’s watch have come under criticism. An irrigation system was planned without the say of the indigenous people who live there. Huawei was involved in a scheme to create an urban monitoring system, until the Philippine senate called for an inquiry. The Chinese contractor behind the massive Kaliwa Dam began work without government permits, or care for the concerns of the locals the dam displaced. Chinese state-owned company State Grid Corporation of China owns 40% of the Philippines’s National Grid, which has also raised concerns (some of them apparently just because the workers were Chinese).

But for all Duterte’s big promises, the Philippines is surprisingly empty of Chinese projects — only two currently being worked on. Current building work listed by the National Economic and Development Authority shows Japan dominating foreign investment in infrastructure projects (21%), compared to China’s 1.4%.

Still, China is the Philippines’s biggest trading partner, their total trade worth double the Philippines’s second-biggest trading partner, Japan, according to the IMF. That makes P.R.C. trade a lot more important to the Philippine economy than it is to China’s.

In January the Philippines was given pride of place on the first list of countries China approved for tourist travel since the pandemic, the same month of Xi and Marcos’s meeting in Beijing. Better to have the Philippines inside the tent, keeping goodwill with its neighbor and economic leverage if need be. China has used trade as a weapon in the past, quarantining Philippine fruit imports over a two-month dispute off the Scarborough Shoal in 2012, only lifting these restrictions when Duterte signaled he was distancing himself from the Philippines’s traditional military alliance with the U.S.

The last thing China wants is an escalation of tensions, likely a reason for the U.S. to assert itself further in the South China Sea — Xi Jinping even had a meeting with Duterte behind Marcos’s back in July, telling Duterte he could play “an important role” in Chinese-Philippine relations. Analysts interpret this as a signal he preferred the tone Duterte had set, in contrast to the U.S. partnership resumed by Marcos.

China has tried to keep things cool in the past by signing several codes of conduct about how they would act, each one non-binding. Their Ministry of Foreign Affairs prominently displays all the joint communiques between the two for peaceful resolutions over the South China Sea, which agree to set up bilateral committees and hotlines. But these are viewed with distrust by Philippine political elites — a bilateral commission for joint exploration for oil and gas in the area, under “preparatory talks” between the two governments back in May, was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Vice-Chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Francis Tolentino claimed the commission could lead to “more [Chinese ships in Philippine-claimed waters] because they can say they now have the right to drill, to conduct scientific marine research,” building more substantial ground for future Chinese claims.

While both sides refuse to budge, China’s hotlines and joint committees can only serve the moral high ground. The Philippine coast guard withdrew from their emergency hotline arrangement with the Chinese coast guard in mid-August, claiming the line had done nothing over the past six years, and that they hadn’t been able to get through to the Chinese side for several hours during the Sierra Madre incident. Meanwhile, China’s naval patrols in the region have only increased since the pandemic, the Philippine government filing 444 diplomatic protests against Chinese activities in the area since 2020.

It remains to be seen if China’s bear hug will smother Philippine protest.