Sinica extra: Bombing Chongqing

An excerpt from "Eve of a Hundred Midnights," by Bill Lascher.

The November 3 Sinica Podcast is an interview with Bill Lascher, author of Eve of a Hundred Midnights. The book tells the story of his first cousin twice removed, Melville (“Mel”) Jacoby, a journalist who covered China during World War II. Mel traveled from Peiping (Beijing) to Chungking (Chongqing), then escaped China to the dank caves where MacArthur’s troops held out on Corregidor in the Philippines.

Below is an excerpt from the book, published with permission from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins.

For most of the hot, suffocating day of June 5, 1941, there were no bombers above Chungking. There were no alarms. There were no screams. There was simply the background chatter of a busy Thursday.

But beginning at about 6:00 p.m. that night, the city’s soundscape shifted. Alarms rang. Storefront shutters clattered closed. Within an hour, eight Japanese planes roared overhead.

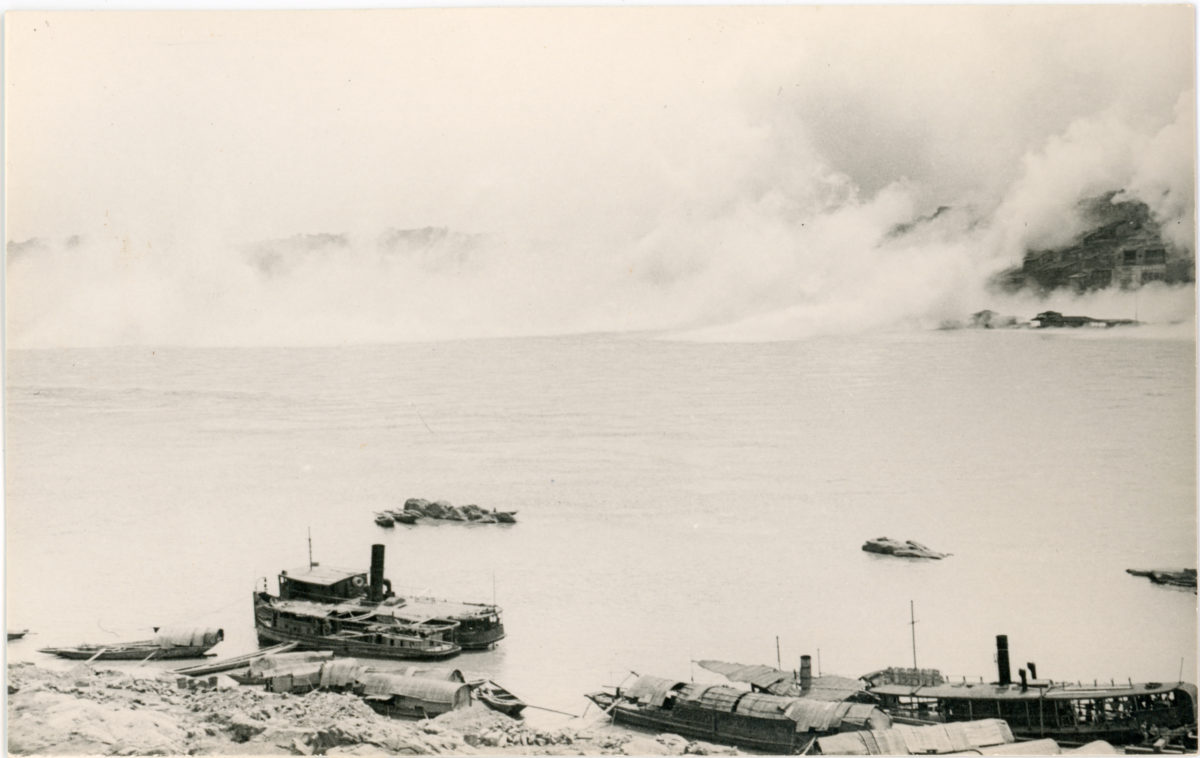

Their crews opened bomb bay doors and showered Chungking with devices packed with kerosene and gasoline. Flaring across the sky, the bombs ignited the papery buildings that packed much of the dense city, replacing Chungking’s daily noise with the crackle of flames.

“Fires lit the city and the sky above glowed pink and red,” Mel wrote two days later in one of his first reports to David Hulburd, his new editor at Time, describing one of Chungking’s most catastrophic nights yet. He had been on the south bank of the Yangtze during the attack.

When the first alert went up that evening, nearly 5,000 people had packed into the city’s largest dugout, nearly a mile and a half long.

At first the city’s air raid warning system indicated that the enemy was gone. But half an hour later, the warning signal returned. More planes were coming. Police shouted for people to return to the shelters. Most had noticed the signal themselves and were already running back toward the gates.

“In one giant shove they crammed, jammed their way back through the monster dugout’s three entrances,” Mel wrote. The weakest in the crowds stumbled, and the panicked crowds shoved forward over them even as more fell beneath their feet. “The sweltering crowd grew restless after the bombs had fallen,” Mel wrote. “Hundreds of them shoved towards one of the three entranceways for fresh air and a look-see.”

However, the shelter’s gates were locked, and guards wouldn’t reopen them. A few minutes passed, and the crowds began crashing against the main gate. Its guard relented, and the crowds streamed out to watch their city burn.

Now the city heard bones and flesh crumple as people ran in every possible direction. They bellowed. They cried. They sobbed. They gasped for air in the choked tunnels and howled in pain as they clawed and bit at one another as they tried to break free.

“There was shouting and cursing as only China knows it,” Mel wrote. “Women beating against those in front, children trying to find air. Scores went down to their death. As the sound of Japanese planes droning overhead came to their ears the shoving became even more intense and the bodies along the floor of the passageway more numerous. The excitement spread through the dugout like a swift breeze.”

As the next round of bombs fell, those inside the dugout again panicked and surged back against the entrances. Waves of frightened residents rushed both into and out of the shelter, each stampede crushing the other. The guards were so overwhelmed that they locked the entrance gates again, trapping the frightened masses inside, leaving those within to claw, scratch, and shove at one another.

Two more waves of bombers attacked, drawing the crisis out for hours. As ever more people were crushed and asphyxiated, bodies piled higher. “Whole families went down into the damp, dirt floor tearing at each other,” Mel wrote. “Body packed against body, walls of flesh grew.”

Finally, by midnight, the raids were over. Elsewhere in Chungking people emerged from the dugouts with their children in their arms. Exhausted, but alive, they headed home and tried to get to sleep.

“Cars honked along the streets again, government people and big merchants came out of their better-made dugouts only half tired, half joking about being kept awake all night,” Mel wrote.

But in the city center another two hours passed before the public shelter’s gates were opened. Its guards had fled. Once the gates finally were unlocked, few people emerged.

“There were only a few faint cries heard inside,” Mel wrote. First local police and other authorities arrived, followed by Red Cross workers. They found bodies everywhere, some unmoving, a few still writhing.

“Most were dead,” Mel wrote. “Like piles of leering, gasping sardines in a cannery, they were twisted and piled here and there along the dirt-floored dugout. A few arms and legs were twitching.”

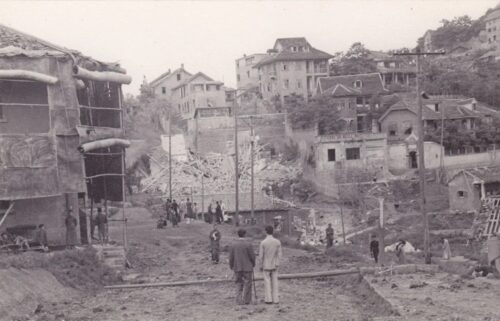

More than 4,000 people are thought to have died in the catastrophe. Blame for the disaster was spread widely. Starting within a day of the attack, air defense commanders were fired, foreign engineers decried shelter designs that limited air circulation and lacked ventilation, doctors excoriated soldiers for not properly removing the bodies, and politicians called for the heads of the municipal officials who cut corners while building the structure.

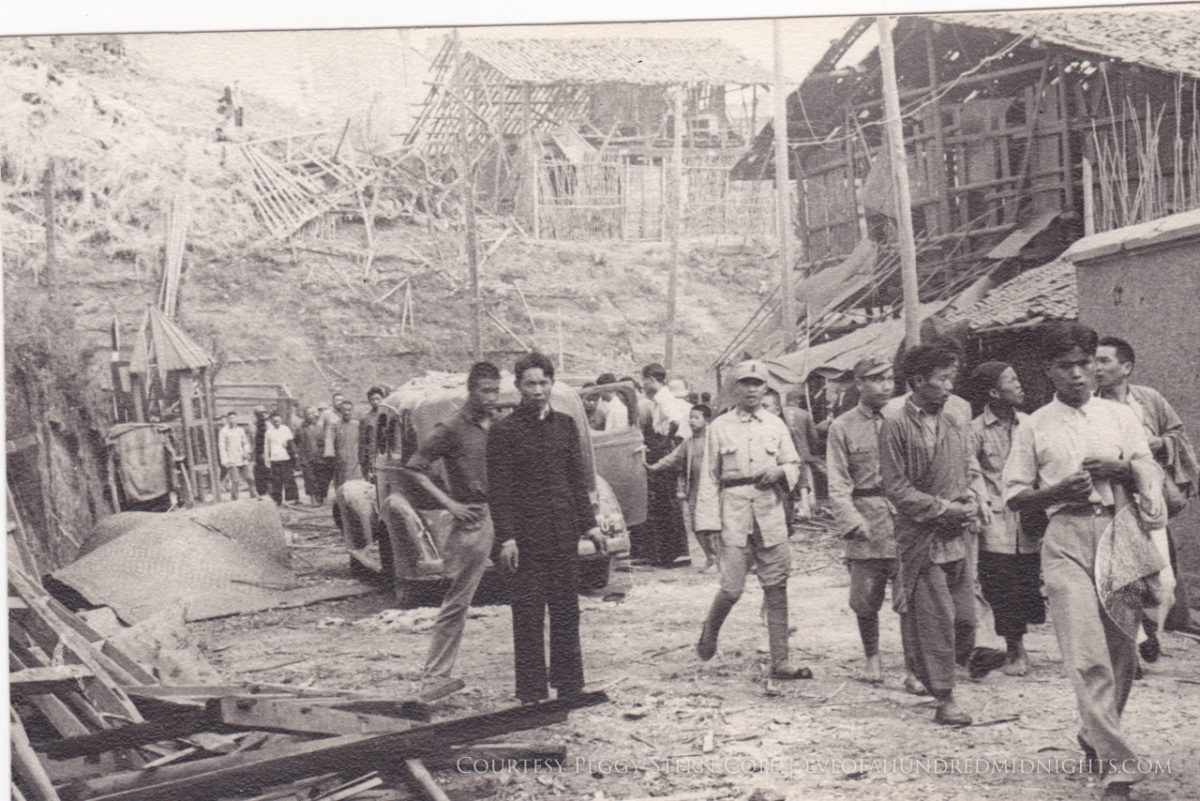

The night after the attack, Mel and the United Press’s Mac Fisher crossed the Yangtze River from the foreign district on the south bank to observe the recovery. On the sampan crossing the river, the reporters met survivors, one of whom had lost two brothers in the disaster. He claimed he saw Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek burst into tears when he visited the dugout at 4:00 a.m., a scene that was widely reported elsewhere.

Once Mel reached the dugout, he pulled out his camera. At the main entrance, seeing dozens of masked Chinese soldiers carrying dead bodies from the shelter’s black maw, he snapped a picture. On a nearby staircase he saw the dead still piled and sprawled where they had fallen an entire day before. He clicked the shutter again. Nearby, Red Cross workers threw the victims’ corpses into a truck, and Mel took another picture. He saw a lifeless child crushed by the stampede and took one more picture.

From Eve of a Hundred Midnights, by Bill Lascher. Reprinted with permission from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins.