Do we really need to worry so much about Chinese nationalism?

Kaiser Kuo reflects on Chinese nationalism and its interpretation.

We live in an age of rising nationalism, and this is most certainly cause for concern. Nationalism is a potent ideology: It tends, as the late Cambridge philosopher Ernest Gellner once observed, “to prevail with ease over other modern ideologies” in the places where it takes root. Nationalism — distinguished in its current usage from the more innocent “patriotism” by its identification of an enemy, by its zero-sum mentality, and by its stridency — is an isotope that, however volatile and unstable, nevertheless has a long half-life and lasting toxicity.

Chinese nationalism has long been an object of interest, and rightly so: It has, after all, been an active ingredient in the Chinese ideological mix since the Qing court’s first mid-19th-century collisions with the imperial powers. Fifty years ago, the great intellectual historian of China Joseph Levenson noted that every idea that’s been advanced in Chinese political life has been an answer to the question that has framed and defined modern China’s history: How to make the nation wealthy and powerful. It has been an essentially nationalist quest, and even the proponents of liberalism in the Republican era championed the values of the Enlightenment only instrumentally as the secret to the West’s wealth and power. Where liberal and national commitments — the means and the ends, respectively — came to conflict as they were destined to do, the ends invariably trumped the means.

We frequently read about how nationalism is supposed to have filled the ideological and moral vacuum left when belief in Marxism-Leninism collapsed. We read reporting on the latest, often curious manifestations of Chinese nationalism, such as the young, mostly female “Little Pinkos,” or xiao fenhong, who stridently defend China’s national honor online, or the odd theoretical inspirations of the “angry youth” admirers of the Nazi political theorist Carl Schmitt. There are crackdowns in the universities to rid curricula of the taint of “universal values.” An evening spent channel-surfing Chinese TV, with movies about the War of Resistance against Japan and the “War to Resist America and Aid Korea” in steady rotation, leaves no doubt that the current leadership clearly wants to keep the embers glowing, a wave of the fan now and again sufficient to produce flames. Chinese nationalism really is a thing.

Wilting, garden-variety nationalism

But nationalism in China today is not comparable in any meaningful way to what we’ve witnessed in recent years in Russia, in India, in Hungary or Poland, in Greece — or even, arguably, in Trump’s United States. It simply lacks that virulence. While dismissing it as a merely fringe phenomenon would be unwise, so, too, would overstating its ubiquity or its impact — and this, by far, is the more common error.

The Chinese nationalism alive today is, by and large, your garden-variety reactive nationalism, responding with decreasing vigor to half-remembered humiliations visited on China in a receding past. Lacking the fresh sting of recency and pushed into more distant recesses by China’s many successes, these humiliations are kept alive in no small measure by the artificial respirator of state-sponsored patriotic education. But it is the Party-state, too, that has kept nationalism in check: It has been prevented from cohering into a force capable of hijacking the CCP’s agenda. In its neutered form, it can be harnessed safely to vague projects like the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” and the “Chinese Dream.” Unlike Russian nationalism or Indian Hindutva, today’s Chinese nationalism lacks the kind of traditional institutions or religion around which it might cohere. Given the near-universal and largely unquestioned embrace of the primacy of development, the so-called Neo-Maoists have an understandably hard time gaining any traction. Japan still offers an enemy on whom nationalists can reliably focus their angry ardor. But the other would-be enemy — for all its sanctimony and its hegemonic interventionism — is a hard one to get the instinctively Americophilic people of China to hate.

To be sure, nativist and self-consciously nationalist movements been behind horrific paroxysms of violence in China, most conspicuously in episodes like the Boxer Rebellion at the dawn of the 20th century. Anti-Americanism, even if ostensibly in the name of the workers of the world, took on a conspicuously nativist form during the Korean War and well beyond. In more recent years in China, we’ve seen violent anti-Japanese demonstrations like those in 2005 and 2012, as well as occasional outbursts of anti-westernism, as in the aftermath of the bombing of China’s Belgrade embassy in May 1999: I felt the violence there firsthand. Nationalism is animated, in some quarters, by unalloyed revanchism, and it finds frequent expression in irredentism: Even quite cosmopolitan Chinese people one wouldn’t otherwise suspect of jingoism will often bristle at any suggestion that Taiwan or Tibet ought to be independent, or that Japan perhaps has a legitimate claim to the Diaoyu Islands.

But the appeal of nationalism in China appears to be dwindling. A recent paper by Alastair Iain Johnston of Harvard University, examining survey data measuring nationalist attitudes in the Beijing area over a period of 13 years from 2002 to 2015, suggests that at least in the vicinity of the capital, nationalism is indeed in decline. Johnston, aware that Beijing is not necessarily representative, notes that his findings nevertheless accord with nationwide surveys measuring those attitudes.

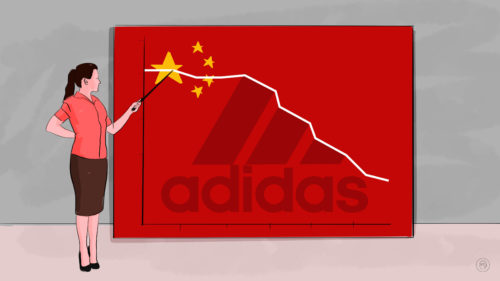

The rising nationalisms of our times — and Trump’s “America First” approach in particular — may even have the ironic effect of diminishing nationalism’s appeal in China still further: Xi Jinping has, after all, stepped (even if opportunistically) into the role of standard bearer for globalization. His unapologetically globalist Davos speech played well at home. And if nationalism has an opposite number today, it is globalism.

What has sapped Chinese nationalism’s potency?

In his recently published book Age of Anger, Pankaj Mishra explores the roots of today’s populist nationalism, looking for the common denominator that links Brexit voters, Trump’s passionate base, the French National Front faithful, BJP supporters in India, and ISIS recruits. He finds the roots of angry nationalism — and really, there’s no other kind — in the restless, resentful energies of immiserated and disaffected stragglers, who have formed unfulfilled and ultimately unfulfillable desires for the the things that others desire — what he terms “appropriative mimicry,” which now happens on a national scale. Thus it has always been: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the “bear” who could never penetrate the salons of mid-18th-century Paris and turned viciously on the well-heeled philosophes, was in Mishra’s telling the archetype for the “men of ressentiment” who bedevil the current age. Why the surge now? Because in the last 30 years, information and communications technologies and the forces of economic globalization have thrust us all into a “common present,” in Hannah Arendt’s term, where the inequalities of circumstance become impossible to ignore: “Individuals with very different pasts find themselves herded by capitalism and technology into a common present, where grossly unequal distributions of wealth and power have created humiliating new hierarchies,” he writes.

It’s a compelling argument. But while he includes Xi’s China in his litany of states representing this new nationalist wave, it’s telling that Mishra — who has spent a good amount of time in China, and who I’ve personally interviewed three times — had to reach back 20 years to the publication of the now-infamous China Can Say No in 1996 for a good example of a substantial nationalistic text. China has an ample supply of its own “men of ressentiment” who feel that same ennui, the anomy, the malaise, the vexation over the “soul-killing venality” so in evidence in Chinese cities. These men even have a name: They are the diaosi, the self-described “losers,” who’ve reappropriated this name for them coined originally as an insult. And insofar as there are foot soldiers for nationalism in China, the diaosi fill their ranks, and share many if not most of the characteristics Mishra so astutely observes among the new populist nationalists everywhere: They tend to be misogynistic, opposed to so-called “political correctness,” intolerant, and admiring of authoritarianism.

This is remarkable for its ordinariness: No ideology akin to the Eurasianism that has emerged as the theory in Russia’s new nationalism, as the Financial Times journalist Charles Clover, now based in Beijing, wrote in his excellent 2016 book Black Wind, White Snow. There is no overarching organization, and nothing much animating it beyond everyday resentments. Why, then, is there no nationalist movement? Part of the answer is of course that the Party-state has effectively co-opted what might have been a movement, effectively channeling it, as I’ve suggested, into Party-approved projects. China’s leaders have wielded the tools of control and coercion — internet censorship is probably the best example — to actively prevent organization outside of anything explicitly state-sanctioned. Dissemination of content the Party deems too inflammatory is almost impossible. The leadership has stood over the fire pit of nationalism with a fan in one hand and a fire hose in the other. They can whip up the flames to intimidate, or to point to during a negotiation so their choices appear constrained by a loud domestic constituency. But with the hose they can also keep that fire from leaping out and burning down the valuable surrounding countryside, and they’ve demonstrated repeatedly their ability to control the flames.

It’s worth noting, too, that the Party never calls nationalism “nationalism” (民族主义 mínzú zhǔyì), opting instead for the less value-laden “patriotism” (爱国主义 àiguó zhǔyì). Minzu zhuyi connotes ethnic (minzu) chauvinism, and as the CCP defines China as a multiethnic country with 56 recognized minority nationalities, it naturally steers away from the word — just as Russia, even under Putin, uses the word “nationalism” only as a pejorative. (Ironically, this is not the case with the nationalism of the Trump era; Stephen Bannon even used the word to describe Trump’s inaugural speech).

Part of it may simply be economic: Nationalism just doesn’t find sufficient purchase in a China where the fruits of globalization over the last 30 years, as inarguably uneven in their distribution as they’ve been, have nevertheless been enough to prevent the pooling of resentment and to sap nationalism’s potency.

I would submit that one important factor is cultural, and has its roots in the early 20th century. Then, especially during the New Culture Movement (ca. 1915–1925), which historians correctly elide with the May Fourth period, China’s intellectuals repudiated traditionalism and, rightly or wrongly, located the sources of China’s weakness and poverty precisely in premodern tradition — in the Confucian family structure and the “slavish” habits of mind it supposedly inculcated, in the stubbornly unscientific cosmology, and so on. The cultural iconoclasm of the New Culture intellectuals came to inform the posture of subsequent generations toward tradition, and in a very real sense, the spasm of anti-traditionalism in the Cultural Revolution was only the New Culture ideology taken to its illogical conclusion. By the time the dust settled after the Cultural Revolution, what remained of “tradition” that might serve as a foundation for nationalists? Ironically, the only nationalists who are suffered to exist in any organized fashion in China today are the Neo-Maoists.

The specter of Chinese nationalism is invoked with some frequency by those who would douse the ardor for multiparty democracy. It’s invoked in this way, indeed, by many a liberal. It’s a twist of course on the familiar sùzhì 素质 argument — that the unwashed Chinese masses just aren’t ready for democracy. In this telling, the problem is that freed of its fetters, nationalism would run the table: “If we had free elections in China tomorrow,” said one liberal Chinese friend of mine, “we would elect Hitler next Tuesday and be at war with Japan by Friday.” The message is “Careful what you wish for.” In this view, some gratitude is perhaps due to an illiberal Party that serves as a bulwark against a nationalism that would be more illiberal still.

The jury is out on what would actually happen were that bulwark to be dismantled, but I’m coming around to the view that we’ve exaggerated its proportions and the dangers it poses. While I’m not suggesting that Chinese nationalism is innocuous, and is not something we ought to continue to concern ourselves with, we really should keep in mind that nationalism is an ideology that feeds on perceived slights and tends, conversely, to diminish when it can’t claim to feel put upon. We should recognize it for what it mostly is — the unsurprising residue of China’s historical experience, utterly comprehensible by anyone with the least capacity for empathy, and remarkable mainly for its relative impotence.