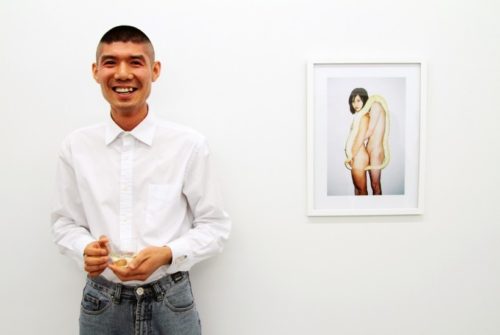

The naked poetry of Ren Hang

The short life of a provocative and talented photographer who defied social conventions.

There was an outpouring of grief from around the world on February 24 as news spread that Chinese photographer Ren Hang 任航 had died at age 29, after reportedly jumping from a building in Beijing. Fans of his playful, overtly sexual work expressed their feelings over social media, while galleries and art publications from Shanghai to Paris to New York issued statements or re-released interviews in his memory.

Ren, who was born in the northern city of Changchun in Jilin Province in 1987, gained international renown for his unique perspective on youth in China. His intimate, graphic shots of his friends seemed to underline the fluidity of their sexuality and their comfort with nudity. Yet ironically, it was this focus that prevented Ren from gaining widespread success within China. Due to anti-pornography laws dealing with nudity, he was unable to exhibit much of his work in his own country.

Despite this, Ren remained dedicated to China, to photographing his Chinese friends and peers, and to pursuing his work in Beijing. And while his images were more widely shown abroad, his loss is felt keenly in China and in Beijing, the city where the artist remained firmly rooted and where he found his artistic style.

“The more I’m limited by my country, the more I want my country to take me in and accept me for who I am and what I do,” he told Vice Japan in 2013. “I love China, and I like shooting Chinese people.”

Black wigs and pig hearts

In his photo shoots, which took place atop buildings, in parks and forests, and in sparse studios, Ren was known for his distinctive speed, decisiveness, and spontaneity. Right hand there, left foot there, body like this, he would direct. Sex organs, breasts and butt holes were not covered up, but featured, or accentuated with props and close-ups. In quick succession, naked bodies and hands were stacked, splayed, and sprawled. Then his film-loaded, point-and-shoot camera would start snapping.

In his photo shoots, which took place atop buildings, in parks and forests, and in sparse studios, Ren was known for his distinctive speed, decisiveness, and spontaneity. Right hand there, left foot there, body like this, he would direct. Sex organs, breasts and butt holes were not covered up, but featured, or accentuated with props and close-ups. In quick succession, naked bodies and hands were stacked, splayed, and sprawled. Then his film-loaded, point-and-shoot camera would start snapping.

“The bodies, to him, were like building blocks that he could manipulate and play with, and in the process, gender and sexual orientation break down,” says Stephanie H. Tung, Ph.D. candidate in modern and contemporary Chinese art at Princeton University, who interviewed Ren for Aperture and became familiar with his work while she was a junior curator at Three Shadows Photography Art Center in Beijing.

Tung says that “seeing these young Chinese models, so brazen and carefree, is quite shocking” within the larger context of a typically modest China. And yet she classifies Ren as “part of a younger generation [of artists] that looked inward. They don’t try to make statements about the state of Chinese society or identity directly. They’re much more interested in play, documenting the lives of their friends and loved ones. Their work is very personal.”

Ren’s friend Helen Feng, front woman for the Beijing-based rock band Nova Heart, agrees, saying the emphasis on sexuality was intuitive, not political, for Ren.

“I think it was just naturally happening in his life. He was young, in his twenties, he was exploring sexuality, and that was what he wanted to show,” says Feng, who first met Ren at a photo shoot involving black wigs and real pig hearts. “I had met a lot of photographers, but it was the first time that I met somebody who had an eye for making iconic photos so quickly,” she says of the experience.

The artist as a young man

Ren began taking pictures after he moved to Beijing at age 17 to study advertising at the Communication University of China. He carried his camera everywhere, says author Zhou Yuanyuan (周源远), who became a close friend of Ren’s around 2008, when Ren was still a student.

Ren began taking pictures after he moved to Beijing at age 17 to study advertising at the Communication University of China. He carried his camera everywhere, says author Zhou Yuanyuan (周源远), who became a close friend of Ren’s around 2008, when Ren was still a student.

“He wanted to capture everything,” says Zhou.

In those days, Ren fed on the Beijing art scene, making the hour-long trek from his apartment outside the East Fourth Ring Road to the city center for rock shows. Around 2008, he began to plug himself into it more, publishing about 10 issues of his own online magazine, Moon, and shooting artwork for bands or events. Ren also began producing his own monographs (he eventually self-published 16 of them all told, including one volume of poetry) and showing his work at small venues.

Lu Zhiqiang 吕志强, director of the Beijing live music venue Yugong Yishan, remembers being approached by a curator friend of Ren Hang’s about holding a show around 2010. “I said yes immediately,” he says after seeing how distinctive Ren’s work was. “Not many people heard of his name before. But that night, around 500 people from both the music and art circle had turned up — it was overwhelming.”

In addition to his photography, Ren was a prolific poet. His poetry, published online on his website, usually comprised a handful of short lines, their tone ranging from humorous to sensual to dark. This online collection of poetry, starting in 2007, predates his website’s photo collections by a year.

“He was, in a way, a poet who just happened to be a great photographer,” writes Tim Crowley, assistant director of KWM Art Center in Beijing, where Ren’s work is currently being shown, in a press release after the artist’s death. Crowley says that while Ren was laconic about his photography, “his eyes lit up and he became very alert and enthusiastic” when asked about his poetry.

Going global

Yet photography was what brought Ren attention. As he gained traction for his work, Ren was able to show carefully selected sets of photos at a few major Chinese centers of art, including a show curated by photographer Rong Rong 荣荣 at Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in 2011, and another at Three Shadows Photography Art Center in Beijing in 2014. Ren’s work is currently part of a joint exhibition with French-Chinese painter Li Xinjian at Beijing’s KMW Art Center.

But in China, he was less on the radar than some of his contemporaries. “You never really heard too much about him domestically. He wasn’t really analyzed that way,” says Steven Harris, director of Shanghai’s photography-focused M97 Gallery, referring to conversations in the gallery and arts scene in China.

Instead, Ren was meeting a growing international interest that pulled him out of the country more and more for jobs and shows from Tokyo to Paris to Copenhagen to New York. He was part of Ai Weiwei’s 2013 show FUCK OFF 2 at the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands, and has shown in over 20 solo and 70 group shows since 2010 (including those in China). His work is currently on display in two solo exhibitions, one at Amsterdam’s Foam Museum and the other at the Fotografiska Museum in Stockholm. His first complete monolith, Ren Hang, which runs 312 pages in French, English, and German, was released for international sale earlier this year by Taschen.

“Ren grew from a young photographer to an artist,” says his old friend Zhou, who published a short personal memoir (in Chinese) of his relationship with Ren on WeChat two days after he died. He contrasts their growing recognition, prior to Ren’s death, with the days when they had both newly finished college. “Those days when we had no money, no fame, everything was pure.”

Success did not stop Ren from experiencing depression, which he had long lived with and documented in a journal (in Chinese) and which appeared as a theme in his extensive collection of poetry. In one poem, he writes: “Life is really one/Precious gift/But sometimes I feel that/It has been given to the wrong person.”

These words provide a glimpse into the man usually hidden behind the camera, but they do not dictate how he will be remembered, say friends who knew him in Beijing. Instead, they describe a caring man and carefree artist, who was always open to new things.

“Most of us find that which is unique reprehensible,” says Feng of Nova Heart, “but he had a much-higher sense of tolerance. He was able to see things in a way that he found beautiful, and he was able to capture that beauty — that was his eye.”

All images in this article are from Ren Hang’s website, where you can find a large gallery of his photographs. You might not want to view them at work, due to sexual content.