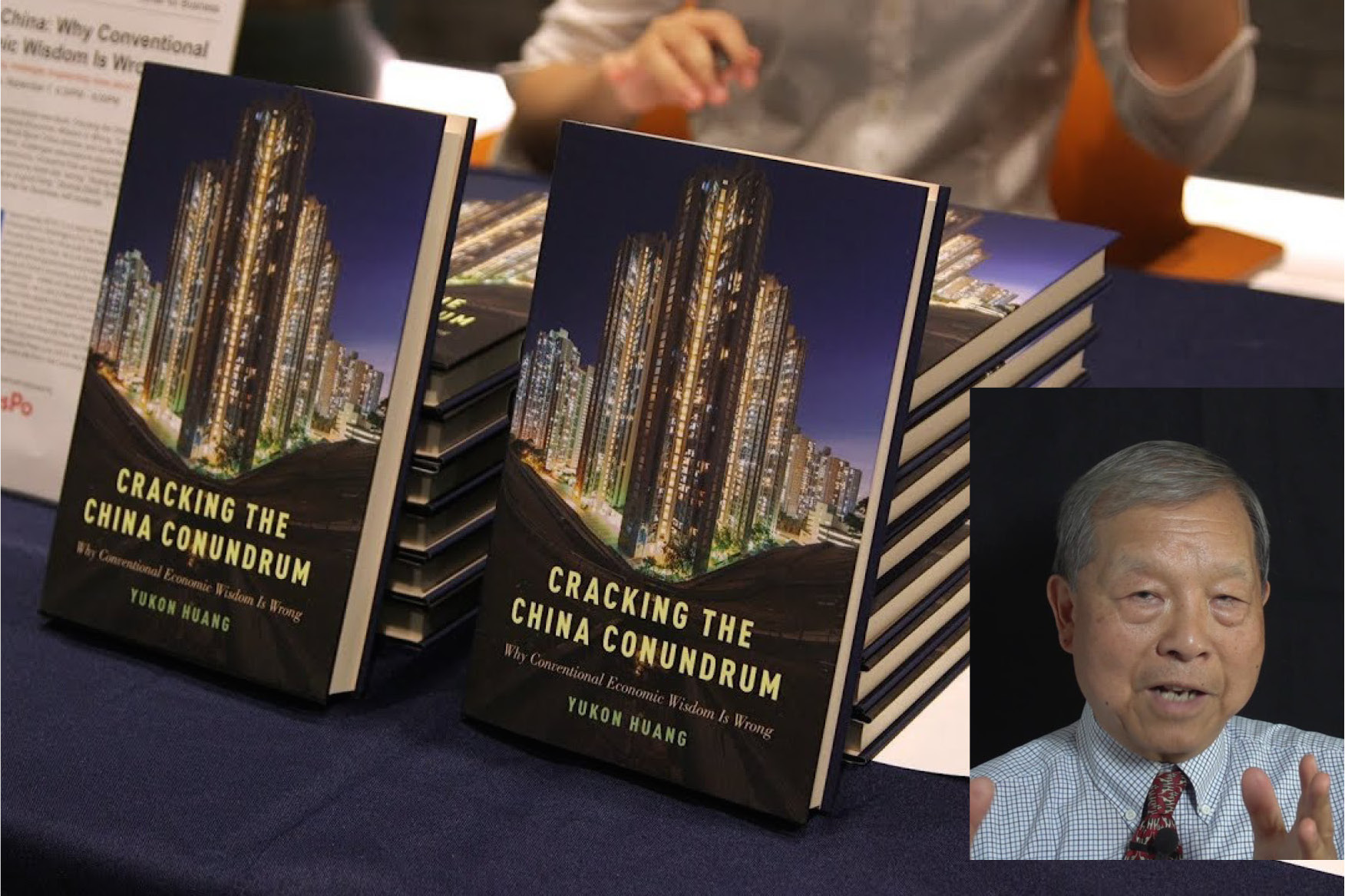

‘Cracking the China Conundrum’ makes bold claims about the nature of China’s economic reality

The latest book by renowned economist Yukon Huang offers fact-based rebuttals to popular assumptions, and argues, above all, that conventional western economics will not save China.

Book review: Cracking the China Conundrum: Why Conventional Economic Wisdom Is Wrong, by Yukon Huang (Oxford University Press, 2017)

Yukon Huang’s new book, Cracking the China Conundrum: Why Conventional Economic Wisdom Is Often Wrong, offers a breath of fresh air in an environment of fake news and media-driven distortions. The author, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment who was the World Bank’s country director for China, offers fact-based analysis and goes to bat against all extremes, both Chinese optimists and economic pessimists, in an attempt to illustrate the true picture of China’s economic and political situation.

Huang dismantles strongly rooted positions of both Chinese and economics experts, and criticizes the opinions offered from those who view the country through the narrow lens of modern, Western-style economics. The fact that China has been able to grow into the world’s second-largest economy without Western-style free markets, democracy, or guarantees of human rights — the pillars on which the Western world has built its success — is unsettling for many, as Huang acknowledges. China’s success indirectly challenges these principles and calls into question if there really is a “one size fits all” approach to building a country’s strong financial and economic structure.

Yet Huang cautions against viewing China’s economic growth as “unstoppable.” Yes, the country ranks second in overall nominal GDP, but it comes in 80th in per-capita GDP. It also has an impoverished and huge migrant population pouring into major cities in search of work. Huang notes that even by 2030, only one-tenth of the Chinese population will be relatively well off (defined as within the top 10 percent of global incomes), compared with about 90 percent in the U.S. and Europe. Despite its impressive economic stature, Huang notes that the country’s tactless soft-power skills and its underdeveloped alliances in the international arena leave it far short of “great power” status, at least for the time being.

Cracking the China Conundrum is not for the casual China reader, nor the economic novice. It is filled with data on China’s economic performance, even as Huang admits the country’s statistics are not without methodological problems (he even points out that the majority of China’s official economic numbers have been understated over the past decade). But I have to say, the book is not without bias. Huang attempts to dissect several of China’s biggest stereotypes, and while he paints a fuller picture than most, he isn’t always able to offer a multifaceted explanation. Examples include his ideas about the U.S.-China labor market, China’s role in America’s trade deficit, and the nature of China’s so-called property bubble.

The author also touches on less numeric (and slightly more juicy) topics like corruption. While most analysts believe corruption impedes growth, Huang claims China’s overcentralized financial system actually enables corruption to promote growth. He argues that the nature of China’s excessively regulated and bureaucratic system can be a barrier to investments entering the market — if not for corrupt practices, that is. He points out that President Xi Jinping’s crackdown on corruption and conspicuous consumption has actually gone so far as to hinder economic growth, as officials are now overly cautious to make even routine decisions for fear of misbehavior.

Huang falls prey to a common failing of many economists who believe that the economy is the actual focus of leaders’ agendas, rather than just one of their many political tools. He writes that Xi’s campaign against corruption seems to be “another form of ‘concession with repression’ to handle social pressure while keeping the focus on economic progress.” Unfortunately, this stance makes the incorrect assumption that the anti-corruption campaign is not, in fact, corrupt itself. Just as China has used territorial disputes with its neighbors as national rallying cries, it is highly likely that the state’s anti-corruption campaign is being used, at least to an extent, as a tool to take out political and personal enemies. It is worth noting that the number of people detained since Xi took office has not been this high since the Cultural Revolution.

It is indisputable that the author is more informed than most scholars, and maybe even more than several heads of state, on China’s economic affairs. But his glasses are more rose-colored than is sometimes appropriate. China’s problems are not less alarming just because they are more unique, or enigmatic. What’s more, it would have been useful for Huang to acknowledge that China’s leaders can just as easily fall victim to universal human failings of greed, misuse of power, envy, etc., especially within an authoritarian regime.

China’s many systems and institutions are knit together in delicate and complex ways. If any major missteps were to occur — if one piece falls out of place — there is a very real risk of the entire structure falling apart. China needs to embrace change if it expects to survive its next phase of economic growth. But here’s Huang’s book in a nutshell, which is also perhaps its least controversial aspect: Does China have problems? Yes. Will the answers to those problems necessarily come from outside observers and so-called experts? Definitely not.