The stinky cheese saga: What China’s short-lived import ban on soft cheese really represents

If you think China’s brief embargo on Roquefort, Camembert, Brie, and other soft cheeses only affected expats, think again. Local consumers are developing global tastes at astonishing rates.

You’ve probably heard about China’s most recent, since-overturned ban, given that it was stranger than most. The victim was soft cheese, that breed of food known to many for its strong aroma (or stench, to some).

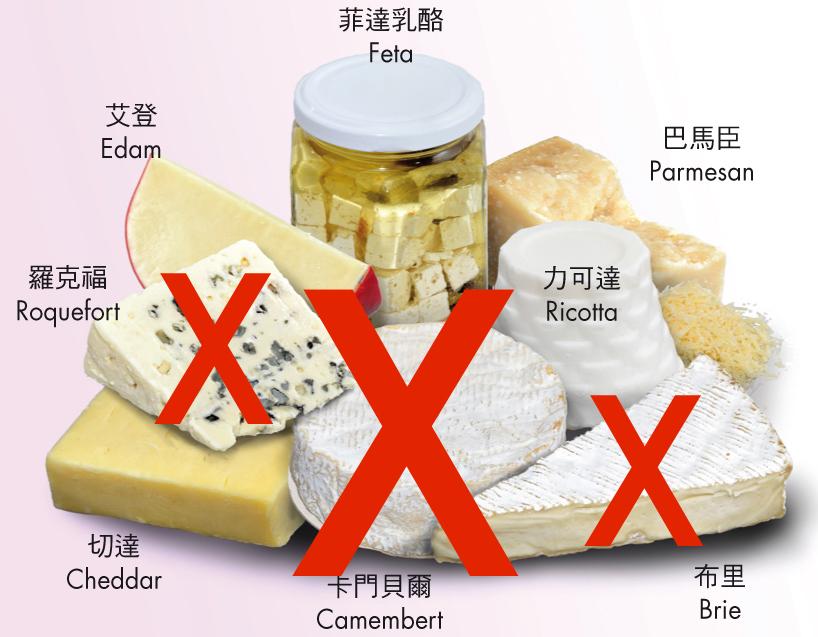

In August, citing potentially unsafe bacteria, Chinese health authorities announced an embargo on soft-rind, marbled, and mold-ripened cheeses such as Roquefort, Gorgonzola, Brie, and Camembert. The reaction was mixed. While dairy importers and European restaurant owners lamented that their businesses would suffer, others saw it as somewhat comical. “To us it was kind of funny,” said Hong Kong-born journalist Joanna Chiu, who grew up in Canada and is currently living in Beijing.

Chiu threw a “Farewell to Cheese” party in October as supplies around the city were dwindling, nicknaming it a “speakcheesy,” a pun on the illicit speakeasy bars that defied anti-alcohol laws during Prohibition. “China bans so many things,” she said. “There are so many government rules — what people should and shouldn’t do — the idea that the government had moved to ban people from eating certain types of cheese struck a lot of people as just kind of funny.”

Much like Prohibition, the ban was short-lived. Two months, in fact. Following a round of meetings between European Commission representatives and Chinese quarantine and health officials, China reversed the ban in late October, effective immediately. “The ban was in place for a short time, so it hasn’t affected our business,” one French restaurant manager in Beijing told AFP.

The strange series of events left an impression on consumers. “It highlighted how arbitrary some of these government decisions are,” Chiu said.

But how arbitrary are they, actually? The global dairy industry was worth $335 billion in 2014 and is estimated to grow to $442 billion by 2019. The cheese industry alone is projected to reach over $100 billion by the same year. China, meanwhile, is the fastest–growing market for cheese imports in the world. Cheese is big business — which makes it a bargaining chip.

China imports 90 percent of its cheese, the majority from New Zealand and Australia in the form of mozzarella for increasingly popular pizza dishes, but all of China’s recent cheese bans targeted EU countries. (To be fair, the U.S. has also engaged in cheese-centered trade spats with Europe.) “This effectively means that China is banning famous and traditional European cheeses that have been safely imported and consumed in China for decades,” William Fingleton, spokesman for the EU delegation in China, was quoted saying in the Financial Times. “There is no good reason for the ban, because China considers the same cheese safe if produced in China.”

Chinese commerce ministry deputy Europe director Wu Jingchun said the ban “is not a political problem but a problem with regulations,” yet the timeline for China and Europe’s tit-for-tat trade battle suggests differently. In May, two months before the cheese ban, the European Commission raised import duties on steel and iron made in China, angering Beijing. Less than a month after the cheese ban, the European Bicycle Manufacturers Association lodged a formal complaint accusing Chinese e-bike companies of dumping products.

But China’s dairy story is also more complex. Most consumers can vividly recall the horrifying 2008 milk scandal, in which melamine-tainted dairy products sickened nearly 300,000 babies and killed six. The highly publicized incident, coupled with a string of dairy contamination incidents in the same year, caused Chinese dairy export numbers to plummet more than 90 percent and resulted in 11 countries blocking all Chinese dairy products.

The events severely damaged the credibility of food safety in China and created a void for foreign dairy producers to fill. China has averaged 12.8 percent annual growth in its dairy consumption since 2000, more than 80 percent of which is milk products. Thanks to increased milk, yogurt, and cheese consumption, the country is projected to overtake the U.S. as the largest dairy market in the world by 2022. With the implementation of the two-child policy, this trend will only grow.

In other words, it is Chinese consumers — not foreigners — who are most affected by a foreign cheese ban. Brie and Camembert, two of the dozens of soft cheeses banned, make up 15 percent of the country’s cheese imports. As China’s middle class expands and its citizens continue to buy from the international market, consumer preferences are changing, and fast. Twenty years ago, it was difficult to find a good slice of cheese pizza in China; now, China imports more mozzarella than any other cheese. It also surpassed the U.S. in 2014 as the number one global market for ice cream.

It begs the question, what other behavioral changes are we missing?

The country’s consumer preferences are morphing, and with a population larger than any other, that means big economic impacts. It also means increased interest in the global market, and not just in food. The basics of marketing teach us that products bring ideas. The spike of interest in cheese, a food that previously had very little relevance in China, serves as a great example of the country’s increasing interest in Western-style preferences and lifestyle choices. What does that mean for the country at large? Trade has been proven since the Roman Empire to be one of the most effective tools for projecting greater influence between nations. Only time will tell what an increasingly globalized market will mean for China. For now, though, residents will settle for enjoying soft, stinky cheese once again.