Historian gripes about access and quality of archives in China

Historian gripes about access and quality of archives in China

Shen Zhihua 沈志华 is a famous Chinese historian who specializes in the history of the Soviet Union, the Cold War, and Sino-Soviet relations. As a professor of history at East China Normal University, Shen earned a reputation for his obsession with archival research, which, according to him, should always be a priority for historians. In a recent and surprisingly frank interview (in Chinese) with Paper.cn, Shen talked the absurd difficulties of obtaining permission to read historical documents in China, and how often they have been tampered with.

At the beginning of the conversation, Shen talks about how he collected a large quantity of declassified archival materials in the 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union. At that time, he paid out of his own pocket for most of the trips that he made to Moscow. But what bothered Shen more than the lack of funding was the quality of the documents he found: “In the U.S.S.R., many government reports submitted to top authorities were written to please superiors,” Shen said. “And archives preserved by Russia are poorly organized compared with those in Western countries such as the United States.”

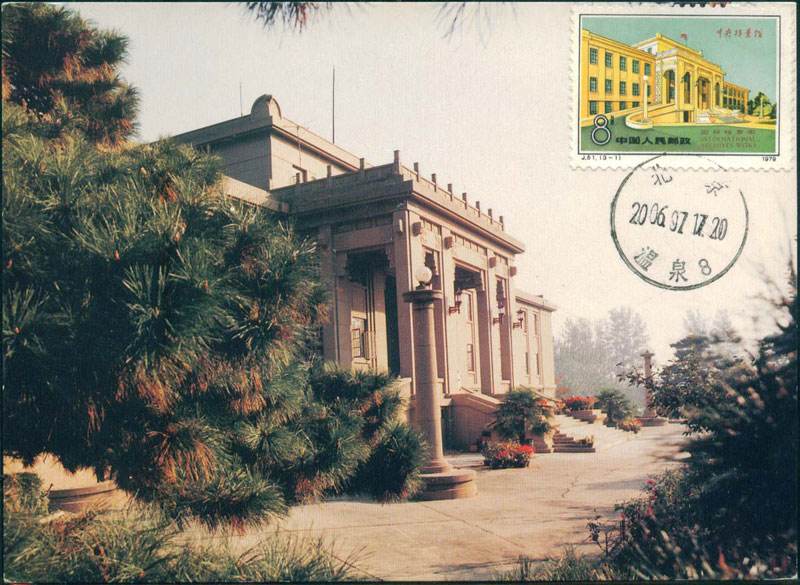

But China is even worse, according to Shen. He recalls three visits to the government-controlled Central Archives in pursuit of some documents. The first time he didn’t give early notice of his arrival and was not allowed into the building. Realizing that there was no way for him to just show up and get in, Shen made a call to Deng Liqun 邓力群, then a senior official in the central government, to ask for help. After Deng gave the institution a heads-up, Shen made his second visit, but he was still frustrated by the staff at the Central Archives: “I was asked which specific document I was looking for, and I replied that I didn’t know and requested an index. Then they said I was not allowed to see the index and needed to give the exact date of the file.”

Shen then compiled a list of over 800 files that he wanted to look at and brought it to the institution. This time, the staff told him that he was asking for too much and was only allowed to see one or two of the files. “I was furious, so I left without seeing any of them,” Shen said.

In addition to the bureaucratic hurdles, Shen said that Chinese historians also need to be careful when using these historical files, as a disturbing number of them are not original. “Many have been modified to serve various purposes,” said Shen, adding that the most reliable archival materials in his opinion are those including a line that says the document was completed and preserved “without review from the person,” referring to whoever is mentioned in the file.

Generally, Shen said, it is nearly impossible to fabricate historical records because there are continuous numbers on them. But in China, destroying archives is fairly common. “Many important documents were destroyed by political figures, apparently on purpose,” he said.

(Image: China Central Archives in 1959)