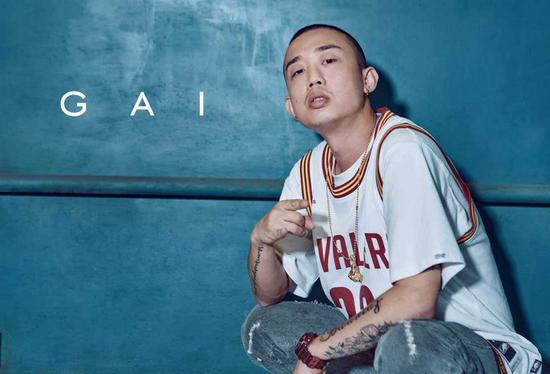

Chinese rapper GAI removed from reality show amidst government crackdown on hip-hop culture

Last week, rumors circulated that Chinese rapper GAI, whose real name is Zhou Yan 周延, had been removed from Hunan TV’s reality competition show Singer 歌手 (gēshǒu). Although no official statement has been issued from either GAI or Hunan TV, media suspects that the Chinese government’s recent move to curb hip-hop culture might be the reason behind the rapper’s sudden withdrawal from the show.

Report: China to ban tattoos and ‘hip-hop culture’ from TV shows

Last Friday, the director of the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television of the People’s Republic of China’s (SAPPRFT) publicity department outlined new rules regulating the content of China’s television programs. According to the guidelines, “artists with tattoos, [representing] hip-hop culture, subcultures (non-mainstream cultures), and decadent [or demotivational] cultures” are no longer allowed to be featured on TV. Artists with “questionable codes of morality or ethics” are also barred.

GAI is not the only rapper to fall victim to the Chinese government’s increasingly draconian control of popular culture. Earlier this month, PG One, aka Wang Hao 王昊, came under fire for the lyrics of one of his old songs, Christmas Eve (紅花會 聖誕夜 hónghuāhuì shèngdànyè), which his detractors denounced for its “misogyny and glorification of drug use.”

Despite later issuing an apology and claiming he had voluntarily removed the track from streaming sites, the rapper’s absence from the live tour of The Rap of China (中国有嘻哈 zhōngguó yǒu xīhā), the rap reality competition show that brought both PG One and GAI mainstream fame last year, would seem to indicate that PG One is still tainted within the industry.

The administration’s clampdown on hip-hop culture also puts into question the fate of shows like The Rap of China, which debuted last summer on iQiyi, one of China’s most popular streaming platforms, and immediately took China’s internet by storm. According to a veteran TV executive in China, the status of shows like The Rap of China remains up to “the will of the government.” Yet at the same time, word is that the auditioning process for the show’s second season is already underway, and faces no obstacles.

Hip-hop goes mainstream in China with billions of views for rap battle reality TV

Will Bollywood movie Secret Superstar break Dangal’s record in China?

Secret Superstar 神秘巨星 (shénmì jùxīng), starring Aamir Khan, broke records over the weekend when it grossed over 100 million RMB ($15.9 million) only two days after its premiere in China, the fastest any Indian film has reached this benchmark. The movie’s box office windfall comes hot on the heels of Indian wrestling drama Dangal’s 摔跤吧! 爸爸 (shuāijiāo ba! bàba) becoming India’s highest-grossing film ever in China last year, and has been read as a further sign that Chinese appetite for Indian movies has grown considerably.

Before Dangal premiered in China, Indian movies had only enjoyed sporadic success in the world’s second-largest market, with breakout films like Three Idiots 三傻大闹宝莱坞 (sān shǎ dà nào bǎo lái wù), which also stars Aamir Khan, being the rare exceptions in a landscape dominated by domestic movies and Hollywood imports. Dangal, however, proved to be a game changer for Indian movies, becoming India’s highest-earning film in the overseas market (it earned nearly three times as much in China as at home, according to Box Office Mojo).

While it remains to be seen whether Secret Superstar can replicate Dangal’s overall popularity, there is little doubt that the movie, which follows a young Muslim girl’s journey to become a singer despite objections from her conservative father, has resonated with Chinese audiences. The film has garnered positive reviews from moviegoers, earning a high 9.5 rating on Maoyan and an 8.0 on Douban. Media outlets like Yiqipaidianying have attributed Secret Superstar’s triumph at China’s box office to its realist representations of social issues in India, including gender favoritism and the tension between individual aspirations and familial expectations, which echo similar problems in China’s society. Yuledujiaoshou, an entertainment news outlet, also pointed out that the existence of Indian movies like Secret Superstar and Dangal, which deal with social ills head on, has satisfied Chinese audiences’ demand for realist, humanitarian dramas, a demand that, unfortunately, domestic movies are unable to meet due to the rigors of government censorship.

The end of ticket subsidies in China?

For Chinese film producers and distributors, the Chinese New Year holiday is one of the most lucrative times of the year in China. According to news outlet D-entertainment, ticket receipts collected during the 2016 Spring Festival week made up almost a fifth of the annual ticket gross in China that year, thanks in large to the record-setting performance of Stephen Chow’s fantasy comedy The Mermaid. And while it’s not every year that the holiday gets a box office juggernaut like The Mermaid — currently China’s No. 2 highest grossing movie of all time, behind last year’s breakout film Wolf Warriors 2 — the holiday season has still remained a significant period for Chinese movie studios. Not only do studios actively try to seek out a release date during this time, they also spend a hefty amount of money subsidizing movie tickets in order to boost overall sales.

This, however, might change as soon as this year. According to reports, SAFFPRFT, China’s top media regulator, has instructed China’s film distributors and online ticketing platforms to curtail their ticket subsidizing practices. Movie studios will no longer be allowed to buy tickets in bulk and sell them at outrageously discounted prices. In the past, a movie ticket in China, which costs 35 RMB ($5.46) on average, could be bought for as low as 1 RMB ($0.16) during Spring Festival. SAPPRFT is now dictating that subsidized tickets can only be sold for a minimum 19.9 RMB ($3.11), and that each movie premiering during the holiday will only be permitted to sell 500,00 discounted tickets.

Assuming that studios and online ticketing platforms adhere to the new regulations, that would mean that the total sum of ticket subsidies allowed for all the movies being released during the holiday — that’s 11 in total — would be in the ballpark of 80 to 90 million RMB ($12.7 million to $14.2 million), which, according to Ent Group, is the same amount studios would typically spend on ticket subsidies for one single movie in previous years. Although it’s still too early to determine whether the drastic reduction in subsidized tickets will impact the holiday’s box office gross, many industry professionals are applauding the government’s move to de-escalate movie ticket price wars that could hurt the market in the long run.