The 12 most noteworthy Years of the Dog in Chinese history

In Chinese myth, the dog came second to last in the race to determine the order of the zodiac — but starting tomorrow, when the lunar calendar turns, it will take pole position. What will 2018’s Year of the Dog bring, and how does it compare to dog years past? We pored through history to get an idea, and below we list 12 different Years of the Dog in order of importance rather than chronology.

Admittedly, we’re guilty of a little recency bias. Could we definitively say 1778 wasn’t more interesting than 2006, or 1526 wasn’t a year that should be remembered? No, we can’t. But records were spotty back then, so we’ll just have to go with what we know.

If you think we missed something, drop us a note in the comments below.

Let’s get started.

1934

1934

Now shrouded in myth, the Chinese Communists’ Red Army began its circuitous 6,000-mile retreat from the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT), in October 1934. The Long March, as it became known, became a seminal moment in Mao Zedong’s 毛泽东 rise to become the undisputed leader of the Communists, and galvanized many young Chinese into joining the Party. It’s also safe to say the Nationalists might have subdued the insurrection, which began in 1927, then and there had it managed to trap the Red Army in Jiangxi Province, where the Long March began. But Mao and his ragtag troops — only a tenth of his army was left by the end of the campaign — lived to fight another day, all the way until 1950 — with a break in between to fight Japanese invaders — when it would secure final victory.

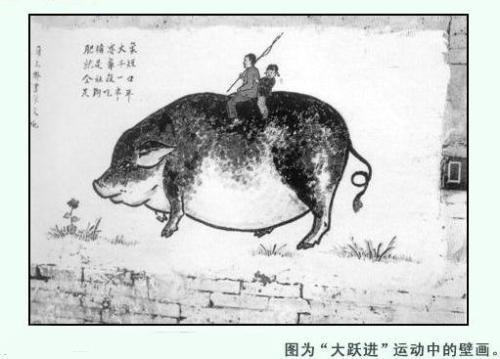

1958

1958

Short of a nuke detonating across the border, nothing that happens in 2018 will likely surpass the devastation Chairman Mao launched in early 1958. The Great Leap Forward, which aimed to rapidly transform China’s agrarian economy into an industrialized society, created a famine that killed millions over the next four years. The figures are disputed, but they’re astronomical no matter how you look at it: Sun Jingxian 孙经先, a professor from Jiangsu Normal University, puts it at 3.66 million — that’s the low end of the estimate — while most other researchers are unanimous in their view that tens of millions of people died during the period; Dutch historian Frank Dikotter places the figure as high as 45 million. Sixty years on, Ian Johnson’s recent article on the event is thought-provoking and recommended.

1898

1898

Zhou Enlai 周恩来, Peng Dehuai 彭德怀, and Liu Shaoqi 刘少奇 — who would go on to shape China in significant ways, as premier, defense minister, and chairman of the NPC Standing Committee — were all born in 1898. But before they could sink their teeth into the history of a new China, they needed an event to precipitate the end of the old. And that event might well have been the Hundred Days Reform, whose failure locked the Qing Dynasty and what remained of imperial China in a headlong path toward collapse.

The Hundred Days Reform was actually 103 days, starting with six intellectuals, sometimes called the “Six Gentlemen” (戊戌六君子 wùxū liù jūnzǐ), who — with the humiliation of the First Sino-Japanese War and Opium Wars fresh on their minds — brought forward a case for sweeping national reform to the Guangxu Emperor. The emperor issued more than 40 edicts that would have overhauled society, from the education system to the military, but the forces of privilege and wealth teamed together with the Empress Dowager Cixi to pull off a coup d’etat and put a stop to the movement. The six intellectuals were executed (along with dozens of others), the emperor was imprisoned until his death in 1908, and the Qing’s fate was sealed.

Revolutionary forces within China, given greater impetus than ever to take drastic measures to overthrow the government, would do exactly that in 1911.

1406

1406

1406 was a time of significant conflict between China and Vietnam, starting with the Ming–Hồ War. The third emperor of the Ming Dynasty, Yongle, ordered an invasion that ended the year after with Vietnam becoming incorporated, as a province, into the Ming Empire.

This was also the year that Yongle fulfilled a longtime desire to move the imperial capital from Nanjing to Beijing. Upon arrival, construction began on what would become the Forbidden City. Major structures within the palace would not be completed until 10 to 14 years later, but the groundwork was set for one of the greatest palaces in the world — home to 24 emperors over 500 years of dynastic rule.

Marco Polo, as relayed in Geremie Barmé’s book The Forbidden City, wrote:

The building is altogether so vast, so rich and so beautiful, that no man on earth could design anything superior to it. The outside of the roof is all coloured with vermilion and yellow and blue and other hues, which are fixed with a varnish so fine and exquisite that they shine like crystal, and lend a resplendent lustre to the palace as seen for a great way round. This roof is made too with such strength and solidity that it is fit to last for ever.

With 9,999 rooms, the Forbidden City is the largest palace in the world, and today is one of China’s most popular tourist destinations, boasting approximately 14 million visitors annually. It remains on pace to realize Marco Polo’s pronouncement of lasting forever.

1946

1946

After a shaky alliance during the Second Sino-Japanese War, full-blown fighting between the Communists and Nationalists resumed. Chiang Kai-shek famously had a chance to end the war when his veteran troops won a key battle in Manchuria and drove the Communists to the northeastern city of Harbin in early June. But Chiang would go no farther, in part because U.S. President Harry Truman and Secretary of Defense George Marshall asked him to pull back. What might have happened had Chiang not heeded Marshall’s request is one of Chinese history’s great what-ifs.

Thousands of miles away, 1946 was also the year that Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump were born.

Let’s check in on the Donald in China, shall we?

1982

1982

Although the Chinese remained the same, the English translation of 主席 (zhǔ xí) was changed from “chairman” to “president.” This move has been regarded by many as a symbolic gesture to distance China from Mao-era politics. Of course, Xi Jinping 习近平 calling himself the “core leader” in 2016 marked a consolidation of power not seen since Mao.

Also in politics, the Third (and final) Communique, which concerned U.S. arms sales to Taiwan, was published. The Communiques were a series of joint statements made by the U.S. and China on the sovereign status of Taiwan, and indicated Washington’s recognition of the Chinese Communist Party as the sole legitimate government of China.

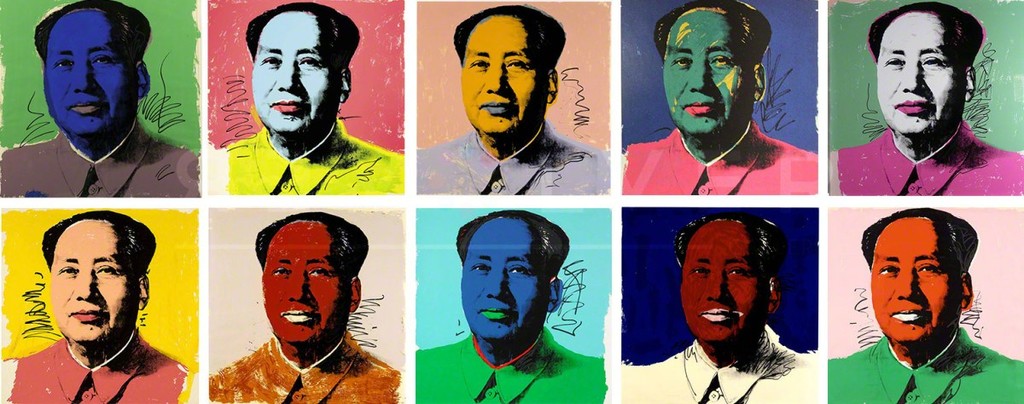

1982 was also the year Andy Warhol visited China. While his famous Mao Series had been completed 10 years earlier, many credit this visit as the inspiration behind his later works on signage and symbology. Warhol also left a sizeable impression on the Chinese; in particular, contemporary artists Ai Wei Wei 艾未未 and Xu Bing 徐冰 credit Warhol for being a key influence on their work.

Also, amid this year of rapid economic change, a meteorite called the Qidong made impact in Jiangsu Province. It was a mass of minerals not much bigger than Donald Trump’s hands, and also apropos of not much, but it’s interesting nonetheless.

1922

1922

Though he had been deposed as emperor in 1912, in 1922 Puyi 溥仪 was married to Wanrong 婉容 in a traditional imperial wedding ceremony. The ceremony, complete with Wanrong’s betrothal presents of 18 sheep, two horses, 40 pieces of satin, and 80 rolls of cloth, took place at the Forbidden City, and was the last of its kind.

Down the coast, Albert Einstein briefly stopped in Shanghai while giving a series of lectures around Asia. It was there that the Swedish consulate officially informed that he had been awarded the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics (it had been left vacant the year prior) for his discovery of the law of photoelectric effect.

Meanwhile, the Republic of China was smack dab in the middle of its Warlord Era, with the north and south engaged in a fight for power, and the two sides further divided into competing factions. In 1922, two cliques battled in what would become known as the First Zhili–Fengtian War. The winning Zhili side, based in modern-day Hebei Province, then plotted to overthrow southern-based Sun Yat-sen, who had years earlier founded the Chinese Nationalist Party.

As if manmade conflict wasn’t messy enough, a massive typhoon in Swatow (now Shantou), Guangdong Province killed more than 60,000, making it one of the deadliest tropical cyclones in history.

518 BC

518 BC

518 BC was when Confucius 孔子 met Laozi 老子: two titans of Chinese philosophy exchanging pleasantries — and pedagogies? ideas? criticisms? rants about the rapscallions within their student body? — perhaps already sensing that they would go on to influence a bazillion people and shape thousands of years of East Asian culture and thinking.

This year was also solidly within China’s “golden age,” known as the Hundred Schools of Thought (770 to 221 BC), which saw a vast number of freelance scholars from a newly formed intellectual class jostling to influence the minds and hearts of a fast-changing, feverishly curious society that welcomed debate, knowledge acquisition, and free expression at heretofore unprecedented levels.

1910

1910

China’s recent Olympic successes are well known, and they can be traced back to 1910: the establishment of the Chinese National Olympic Committee. Team China would not make its Olympic debut until the 1932 Summer Games in Los Angeles, but it’s certainly made up for lost time in the recent past, with Beijing set to become the only city in history to host the Summer and Winter Olympics when it (along with Zhangjiakou) hosts the Winter Games in 2022. (The lineage of the Chinese National Olympic Committee is, alas, not so straightforward; the People’s Republic of China wasn’t invited to the Olympics until 1952. In 1959, the Republic of China — by now situated in Taiwan — decided to stop using the name “Chinese National Olympic Committee.”)

1910 was also the year that the Qing military marched into Tibet and established direct rule in Lhasa, driving out the 13th Dalai Lama in the process. Although their rule was short-lived — ending just two years later – the effects were long-lasting. Some have argued that the Communist Party’s rationale behind its “liberation” of Tibet in 1950, which brought the region permanently under the control of the People’s Republic of China, has its roots in the Qing’s justification of its 1910 expedition: to restore historical Chinese presence in the region.

2006

2006

Perhaps due to the excitement (and anxiety) surrounding the fast-approaching Beijing Olympics, not many new projects were undertaken in 2006 — but some pretty impressive feats of engineering were completed. The main body of the Three Gorges Dam, the largest power generator in the world, and the Qinghai-Tibet railway — the first to link Tibet with Greater China, and the highest railway in the world, passing through heights as great as 16,640 feet above sea level — were both completed. Also launched was Baidu Baike, which currently houses more than 15.1 million articles, three times the number of its Western counterpart, Wikipedia.

214 BC

214 BC

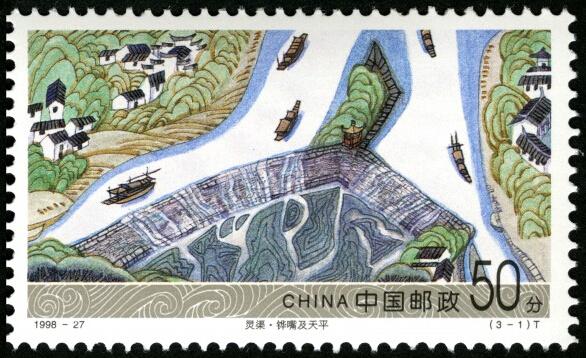

“北有长城, 南有灵渠” (běi yǒu chángchéng, nán yǒu líng qú) — The North has the Great Wall, the South has Lingqu Canal.

The Great Wall is China’s entry as one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World, but the country had another massively impressive feat of engineering that began around the same time: the Lingqu Canal, which was completed in 214 BC. Emperor Qin Shi Huang 秦始皇, the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty, ordered it to be built for military purposes, so that troops and supplies could easily flow from north to south, but during peacetime it carried trade. It is the oldest contour canal in the world and connects the Xiang River with the Li River, allowing 1,200 miles of uninterrupted travel by boat from Beijing to Hong Kong. Along with Dujiangyan and the Zhengguo Canal, the Lingqu Canal is known as one of the “three great hydraulic engineering projects of the Qin.”

1994

1994

Meng Zhaoguo 孟照国, a longstanding UFO fanatic, reported seeing a shiny object plummet from the skies into Heilongjiang’s Red Flag Forest. His claims were deemed true by both the UFO Enthusiasts Club at Wuhan University and the state-sponsored UFO Research Society. In the eyes of some, 1994 was the year that China made its first foray onto the intergalactic world stage.

In less exhilarating but (probably) more consequential news, China stopped pegging the yuan to the U.S. dollar — from 1994 to 2005, one dollar bought you 8.28 yuan. From 2006, the yuan began a managed float exchange rate system, which allows the currency to fluctuate in value within a range set by the government.

With contributions from Anthony Tao. Image by Katie Morton. What’d you think? Let us know. Happy new year, everyone.