Why Chinese companies crush Western tech giants in China

Disclaimer: The following views are mine and not my employer Microsoft’s.

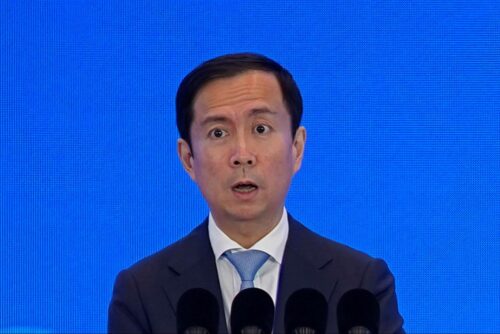

While reading the news, I regularly come across articles stating that Chinese tech giants have the Chinese government to thank for their dominance within China. For example, Bloomberg published an article earlier this month titled “China protectionism creates tech billionaires who protect Xi,” with the author stating, “That’s helped create thriving domestic giants, including Tencent Holdings Ltd. and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.” Mark Natkin, managing director of Beijing-based Marbridge Consulting, was quoted as saying, “As long as they remain protected in the China market, they’ll dominate and use that money to fund their global expansion.”

I’m here to argue: wrong.

About six months ago, when I was traveling to China for work, I was told by an exec of a company, “At first I was only going to copy you, but now I’m going to crush you.” Chinese companies have famously copied American businesses with little to zero compunction, but they are now beginning to innovate at speeds the world has never seen, particularly for the Chinese market. Chinese tech companies would crush Facebook, Twitter, and Google in China even if those foreign companies weren’t banned, and I’ll tell you why.

Relentless hard work

Unless people have seen the Chinese tech culture known as “996,” they don’t understand Chinese tech. [Listen to our 996 podcast for reporting from China’s tech trenches.]

For those unfamiliar, Chinese tech companies regularly work 996, i.e., from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week. What I think a lot of people don’t understand about the Chinese market is that there are many aspects that require pure and utter hard work. Elon Musk knows: “Work like hell,” he once said in an interview. “I mean, you just have to put in 80- to 100-hour weeks every week.

“If other people are putting in 40-hour work weeks and you’re putting in 100-hour work weeks, then even if you’re doing the same things, you know that in one year you will achieve in four months what it takes them a year to achieve.”

Of course, South African Musk’s suggestion received blowback in the Western press, as people argued that working more than 50 hours is counterproductive. The Harvard Business Review weighed in: “In sum, the story of overwork is literally a story of diminishing returns: keep overworking, and you’ll progressively work more stupidly on tasks that are increasingly meaningless.”

But what these commentators and researchers don’t appreciate is that in the age of tech, when you have the fastest feedback loops in history, working 100 hours can work because you get product out faster to receive customer feedback faster, and that leads to faster iterations and finally a market-accepted product. Everything I just said can be done faster and faster. A dev team working 100 hours vs. 40 hours really makes a difference.

When Tencent was making its iterations of the multiplayer battle royale game PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, it created a winner-take-all model: At least three dev teams worked 24 hours a day, working 12-hour coding shifts on different iterations of the same game. The team that created the best version received a winner-take-all prize in the form of a massive bonus. It’s not by chance that Tencent is the biggest gaming company in the world, and certainly not by chance that it dominates the industry in China.

Of course, China didn’t invent this strategy. Apple did it with Apple II vs. Mac. Microsoft’s buildings were originally created for separate product fiefdoms for similar purposes. The point is that Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent, despite their size, can still operate in this manner. This is relentless localization and customer obsession. And they don’t have to worry about media reporting on harsh work conditions, or a social media backlash to 996 hours.

My point isn’t that a system where workers all put in 60 to 70 hours per week is replicable. It’s just that the Chinese actually do it, often without complaint, and Western counterparts simply can’t keep up. Especially in China.

Most global tech companies treat China as just another market

I want to point out a clear distinction between how tech companies operate and how, say, auto companies operate in China. The head of China for many of the auto companies reports straight to the global CEO of the company. It clearly communicates that China is its own unique and separate market. Few tech companies today have a China CEO report straight to the top boss, and that suggests that they don’t believe the China division is worth separating from the overall business. If that’s the case, it’s hard for any company to be dominant in China because it’s not something that’s always on the top of company leaders’ minds.

The other problem with treating China as just another market is it creates a bunch of managers. I don’t mean to use that term as a pejorative. Most heads of China are brilliant, well connected to HQ, and smart folks — but they still have a boss and they need to manage corporate resources. According to a McKinsey report, only 20 percent of China CEOs report to global CEOs, which suggests that there are layers of management that need to be managed, which then gets in the way of operating speed.

Furthermore, especially with more product-focused industries such as tech, a China CEO oftentimes isn’t equipped or empowered to maximize success. For example, most of the people who do backend work or “upstream work” in tech, such as supply chain or product development, rarely if ever report to the China CEO. The China CEO tends to own the go-to market, which produces sales, but it limits their ability to operate as fast as their Chinese tech counterparts, whose primary purview is China and have entire product teams 100 percent devoted to them. How can a manager be expected to beat a faster and more relentless competitor if the manager doesn’t own the product for the Chinese market? It’s not a fair fight.

Localization

Most Western tech firms that come to China try to import the successful aspects of their business models from the West. This doesn’t really work. A great example is gaming. When Western gaming companies come to China, they adopt their Western business model. You pay for a license to play. In China, that’s just not how gaming works, and it never has been. Tencent, for example, has really been the pioneer of freemium innovation, where games can all be played, but players pay for premium items. This has made Tencent create some of the most profitable games in the world, such as Honor of Kings.

Across the tech industry, we have yet to see a Western tech company that has created a completely separate business model for the China market. There are many instances where companies will do something China-specific, such as creating a China entity, joint venture, or even special pricing. But a separate “this is the special business model for China that we don’t use anywhere else” has not been done by any major tech company. Even today, Facebook’s functionality and business models across Facebook.com, Instagram, and WhatsApp outside of China can’t even compete with WeChat’s ecosystem inside of China, so competing in China wouldn’t really be a fight.

Amazon isn’t restricted and it’s still losing to Alibaba and JD.com

While Facebook, Twitter, and Google are blocked in China, Amazon is not, and there aren’t really any restrictions on the ecommerce market. Care to guess what Amazon’s market share is in China today? Less than 2 percent.

Amazon isn’t the first American ecommerce company to lose in China. eBay China was crushed by Taobao. Groupon tried to enter into China with more than $1 billion in its war chest, a headcount target of 1,000 employees, and a goal to hire the “best of the best” McKinsey consultants and investment bankers. What did Groupon China end up with? It couldn’t even get its own name. Moving away from ecommerce, even Uber — which pumped more than $1 billion into China — was simply outmaneuvered by Didi, its nimble and relentless local competitor.

Conclusion

While I can understand Bloomberg and other Western media’s perspective, they tend to overstate the importance of Facebook, Google, and Twitter being banned, and end up falling into familiar narratives of Chinese tech entrepreneurs in cahoots with the government. The boring truth of the matter is, as much as many don’t want to admit it, the Chinese tech companies are successful because they’re genuinely well managed companies with great leaders who know how to execute and who aren’t afraid to innovate. Unfortunately, the headline “Chinese tech billionaires manage companies well” doesn’t sell as many clicks as “China protectionism creates tech billionaires who protect Xi.”