Kuora: The Opium Wars and China’s Century of National Humiliation

Including the loss of Hong Kong.

The Opium Wars and the humiliation that the Chinese endured at the hands of foreign powers remain a source of shame and anger for many today. Let’s explore a bit more with two questions that Kaiser answered on Quora: one originally answered on December 10, 2014, and the other one from March 20, 2017:

What was the First Opium War all about?

and

What do the Chinese think about the Century of National Humiliation (1840–1945)?

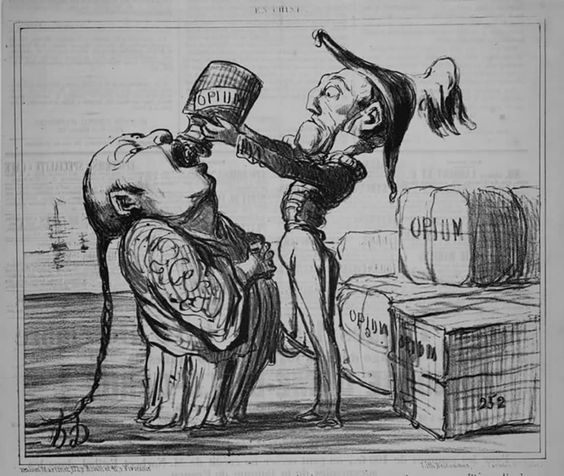

Simply put, by the late 18th century, China under the Qing dynasty had, through its very one-sided trade policies, accumulated very large amounts of silver bullion. Chinese goods like porcelain, silk, and especially tea were being exported through the city of Canton in the Pearl River Delta — the only place where, for limited times of the year, foreign merchants were permitted to trade. Great Britain was paying dearly to feed its appetite for tea, especially. But China had no real interest in most goods that the British wanted to trade. In modern terms, the British were running a huge trade deficit with the Chinese.

But there was one good that the British discovered that they could bring into China that the Chinese would actually buy: opium. They took chests of opium across the Indian Ocean from their colonial possessions in India and sold it in China. Opium addiction spread quickly in China, and among all classes, from the laborers who found it relieved the pain and drudgery of their toilsome existence to the literati, who liked the poetic, dream-like state it could induce. Silver began to flow in the other direction, $500 at a time for a chest of opium.

Chinese emperors banned opium outright in 1800, and again in 1813, but neither of these bans took. There were many Chinese involved by this time in the trade, themselves making good money as they abetted in the poisoning of their countrymen. Finally, in 1838, the Qing emperor Daoguang appointed a very accomplished and highly conscientious scholar-official from Fujian named Lin Zexu as commissioner to suppress the opium trade. He took a very hard line, ordering British (and American) ships to turn over the opium they had in their holds, and seizing the ships forcibly when those orders were refused. He seized and destroyed some 3 million pounds of raw opium.

Not without considerable debate in Parliament, a pro-war faction in London won out, and a fleet was dispatched with the aim of blowing open China to trade, and gaining reparation for the opium that had been seized. It made quick work of the Chinese naval vessels and the fortification of the Pearl River Delta. After the Qing court sued for peace, China was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing, the first of many of the so-called “unequal treaties.” This one ceded, among other things, Hong Kong to the British, and opened up a number of “treaty ports” where the British would be allowed to trade and take up residence.

This would kick off what would become known as the country’s “Century of National Humiliation.”

There are Chinese people today who believe that the Chinese Communist Party has cynically perpetuated the humiliation narrative for its own ends, and there are Chinese people who say they honestly feel it even today, though born many decades since it came to an end in the middle of the last century. But there are very few, I think, who would dispute the basics of the narrative: that China, once a proud, wealthy, and powerful empire with an immensely rich heritage of art and literature, was brought low and humiliated by more technologically advanced powers. Whether they lay the blame more at the feet of complacent rulers, effete bannermen, their own civilizational arrogance, or the rapacity of the imperialist powers, they all would agree that China’s sense of itself was completely upended, its grandeur despoiled, and its very existence imperiled.

We’ve come now to think of this idea of a “national humiliation” as a narrative owned by the Communist Party, but we’d do well to remember that it was felt keenly by pretty much any intellectual of the modern era who cared a fig for the fate of his or her nation. Chiang Kai-shek wrote the words avenge humiliation on every page of his diary for 20 years. If you fail to grasp how central humiliation was to the whole story of modern China, you’ll never really understand China today on its own terms.

There are plenty of younger people for whom humiliation no longer carries what I recently called “the fresh sting of recency,” and there are certainly people within China and, less surprisingly, outside of China who wonder why Chinese don’t just “get over it.” I fully understand why they might feel that way, but think those people lack in fundamental empathy. Though I certainly haven’t experienced it myself, it’s not hard for me to imagine what it feels like to have one’s whole civilizational inheritance — the fundamental cosmology, the core structures of society, the whole approach to pedagogy, the structures of state that evolved over a dozen centuries and worked so well in a premodern context — suddenly just invalidated, exposed as the very reasons for weakness and rot within and for the inability to meet challenges from without. To me, it seems like a bigger psycho-cultural disruption than, say, white southerners in the U.S. having to confront the legacy of chattel slavery, defeat in the Civil War, and Reconstruction.

And yet today in the South, where I now live, we still speak of the “backward glance.”

Also see:

Kuora: China’s dramatic fall from grace and its long road back to respectability

Kuora is a weekly column.