‘Make Americans call us daddy’: Nationalist Chinese rap provokes Penn State CSSA response

At this year’s Lantern Festival Gala in February organized by Penn State University’s Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), a young man named Wang Yifan 王伊凡 performed an original Chinese-language rap song called We Are Penn State. As requested by the organizer, Wang then carried out an improvised freestyle rap: “CSSA gala is so lit, one day we’ll make Americans call us daddy!” he rapped — a line that irritated professors at the university.

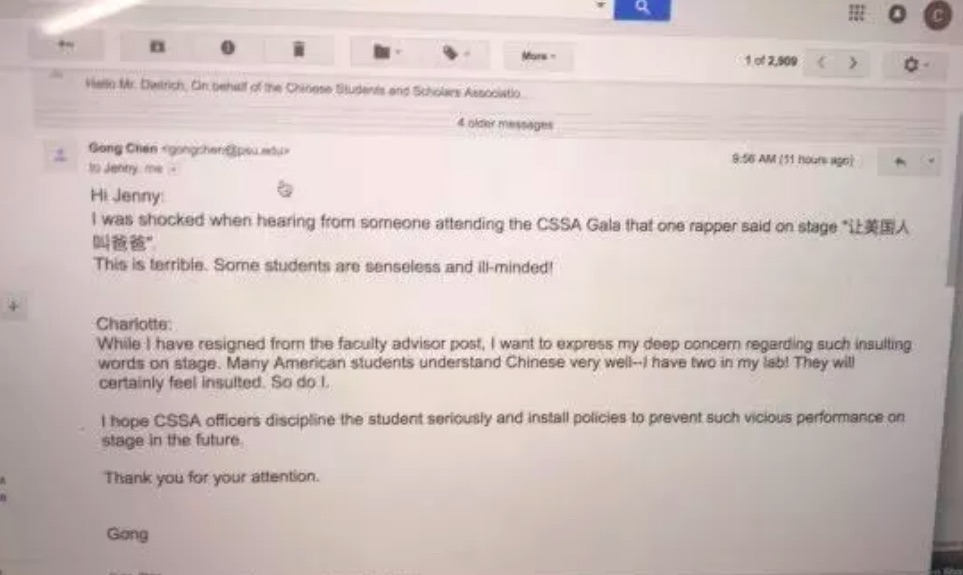

Gong Chen, a professor at Penn State and advisor of the CSSA, expressed his dissatisfaction in an email to another faculty member, Jenny Li: “I was shocked when hearing from someone attending the CSSA gala that one rapper said on stage ‘让美国人叫爸爸’ [ràng měiguórén jiào bàba — make Americans call us daddy]. This is terrible. Some students are senseless and ill-minded!”

Addressing an event organizer called Charlotte, he wrote: “While I have resigned from the faculty advisor post [of the CSSA], I want to express my deep concern regarding such insulting words on stage. Many American students understand Chinese very well — I have two in my lab! They will certainly feel insulted. So do I.

“I hope CSSA officers discipline the student seriously and install policies to prevent such vicious performance on stage in the future.”

Li wrote in response to Chen: “A few [faculty members] and friends did mention [the incident] to me and showed their concern and [discomfort].” Li suggested that the CSSA needed to prevent such occurrences from happening and “really understand the meaning of freedom of speech.”

In an interview with Los Angeles-based WeChat account TilDawn (link in Chinese), Wang Yifan defended himself, saying that in the American context, his lyrics were not very offensive, as it was part of a hip-hop diss song. Wang also said that despite complaints expressed by professors, the university administration never reached out to him.

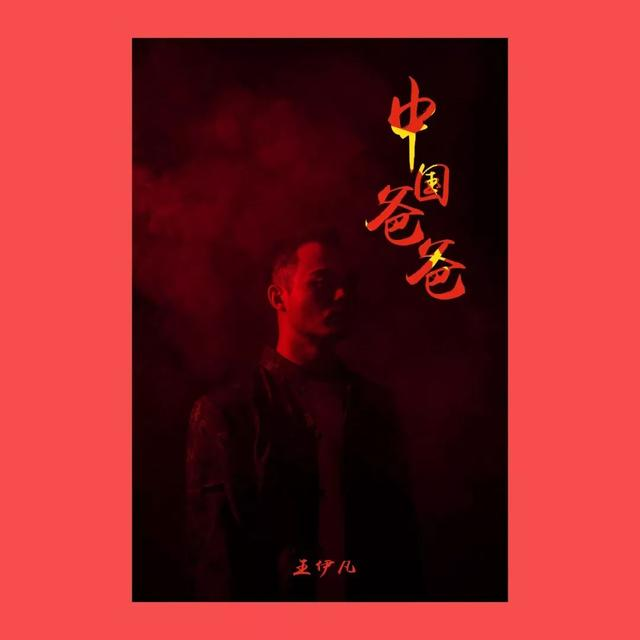

On April 22, two months after the gala, Wang released a Chinese-language rap music video called “Chinese Daddy” 中国爸爸 (zhōngguó bàba) on YouTube (see top embed). After directly addressing Professors Chen and Li, as well as all the “dogs who dedicate their hearts to America,” Wang rapped in the Sichuan vernacular:

Listen / the fresh air / you can freely breathe

Worshipping foreigners / forgetting your ancestry / betraying your native country

I’m talking about you

Bowing and scraping / forsaking good for the sake of gold

I’m talking about you!

Wang references Shuping Yang, the Chinese-born University of Maryland graduate who gave a controversial commencement speech in which she railed against China’s air pollution and lauded America’s freedom of speech and democratic system, calling it “fresh air.”

Wang also refers to Chinese immigrants in the U.S. as “third-class citizens”:

At some points in history / foreign countries have been more advanced than us

It’s fine that you have left China / but I’m going home

going home / after going home / I will build my country

Americans are frightened by the rapid rise of China.

The hip-hop diss rap has received mixed reactions in China. Critics assert that Wang’s nationalist lyrics constituted discrimination against Chinese Americans, while also making it harder on Chinese students seeking respect on U.S. campuses. But Wang’s supporters argue that his lyrics are par for the course for hip-hop.

On April 26, the Penn State CSSA issued a statement on Sina Weibo in which the association acknowledged that Wang’s verbal attacks toward professors Chen and Li have hurt their reputations. “While we respect everyone’s freedom of speech, we should also evaluate whether our remarks are appropriate,” the statement says.

Notably, the statement emphasizes that Wang is not a registered student at Penn State. Wang, on his Sina Weibo account, doesn’t claim he’s a current student, but lists Penn State as an alma mater. It is unclear whether he dropped out or what he is currently doing in the U.S. (he lists “cook at Nittany Lion Inn” on his Facebook profile). In a recent Weibo post he noted that he’s been in the U.S. for six years as a student of business and hospitality.

“Music is a subjective matter,” he also wrote. “The creator is subjective, while viewers also judge subjectively. Different views are permissible. But if anyone can truly look objectively upon the music itself, I’ll be grateful no matter whether you praise or criticize.”

Pan-Chinese nationalism

“If the two professors [Chen and Li] are American, I would politely explain to them that this is freestyle, a form of rap performance, and I did not intend to insult them,” Wang said in the interview with TilDawn. “If they are Chinese, then I won’t bother to explain.

“I think if one speaks Chinese and looks Chinese, people would ask ‘are you Chinese?’ These two professors are not so-called ‘ABCs’ (American-born Chinese), they are first-generation immigrants. Even if they are naturalized American citizens, they were educated in China when the country’s educational resources were precious. In that case, I don’t think there is a problem if I consider them Chinese — zhongguo ren.”

The English term “Chinese” has multiple variations in Mandarin. Huárén 华人 refers to ethnic Chinese, huáqiáo 华侨 refers to overseas Chinese, and zhōngguó rén 中国人 means “people of China,” a term generally designated to Chinese nationals.

The statement from the Penn State CSSA chapter shows that both Gong Chen and Jenny Li are 美籍华人 (měijí huárén) — U.S. citizens of Chinese descent.

The Chinese internet often expects Chinese émigrés — even those with foreign citizenship — to retain allegiance to their birth country. Besides the case of Shuping Yang, Wei Wu — a political dissent from China — received backlash from the Chinese internet after posting a video of burning his Chinese passport after he became an Australian citizen in 2016.

The Chinese State Council administers an office called Overseas Chinese Affairs, or 侨务 (qiáowù). On multiple occasions, Chinese President Xi Jinping has suggested that the Communist Party’s United Front Work Department should “unite all forces that can be united,” specifying communities in the Chinese diaspora as one of the forces.

New stage for Chinese nationalism

Chinese millennials are already familiar with hip-hop culture, despite it being relatively new to China. The country’s first rap reality show, The Rap of China (中国有嘻哈 zhōngguó yǒu xīhā), went viral last summer and became a multimillion-dollar business. Thanks to the popularity of Chinese hip-hop music, an episode of HBO’s Silicon Valley even ended with the Chinese rap song I Want by DMOB — a duo from Xinjiang — which debuted on The Rap of China.

The dudes 黄旭BooM + 艾福杰尼 are from Xinjiang and call themselves the 沙漠兄弟 DMOB (The Desert Brothers). They were apparently a hit on the TV show《中国有嘻哈 The Rap of China》last year: https://t.co/f75UWGGXBY

— Emily Y. Wu (@emilyywu) April 18, 2018

Unsurprisingly, Chinese regulators have not been happy with the vulgar language often in rap, which doesn’t comply with Chinese-flavored socialism. In an effort to shape public opinion, Chinese authorities clamped down on Rap of China superstar PG One, whose lyrics involved sex and recreational drug use. (PG One attempted a recent comeback of sorts into the public limelight, but it didn’t go great.)

But pop culture has been, and still is, one of the favorite weapons of Chinese nationalists. In 2016, a Chinese rap group backed by the Communist Youth League called Tianfu Incident produced an English-language hip-hop music video titled This is China. In the video, the rappers try to inform English speakers that China-related reportage from Western media outlets are biased. One lyric goes, “We have tight gun control laws and don’t fear mass shootings.” Another release from the band, The Force of Red, called white foreign journalists “media punk ass white trash fuckers.”

To Chinese students, America is no paradise

Like many other Chinese students in this country, Wang Yifan knew that the Disneyfied portrayal of America was merely a fantasy. “Although it’s not always the case, Americans often characterize [Chinese students] by stereotypes to a certain extent, and they do not treat us equally,” Wang told TilDawn. “When I first came to America, I had a white roommate and a black roommate. My black roommate was fine, but my white roommate was always targeting me. Once he threw a shoe on me; that was the first time I was bullied.”

In addition to the social pressure they face as foreign students, many Chinese international students realize that the average American’s understanding of China is lacking, and full of biases. “A lot of Americans get off on that idea — that they’re going to liberate the minds of overseas students,” Henry Chiu Hail, an American Ph.D. candidate in sociology, told Eric Fish in his report for The China Project about Chinese students “caught in a crossfire”:

Caught in a crossfire: Chinese students abroad and the battle for their hearts

“They become kind of disenchanted with the notion of objectivity, freedom of expression, democratic values — all of the things they actually came to learn about in the first place,” University of Sydney professor Wanning Sun said in the same article.

A saying has emerged out of recent discussions on this matter: “One becomes more patriotic after one expatriates.” From the U.S., Chinese students get a close and personal view of the shortcomings of American society, from mass shootings to racial discrimination. Donald Trump’s election has also convinced some Chinese international students that the American democratic system is not, after all, perfect.

Wang Yifan would probably agree. “I think Americans have a weak connection, I personally prefer how people in China can talk work while building a personal relationship at the same time,” he told TilDawn. “If you think the air’s no good back home, you can work to improve it, and change with it for the better.”

Wang said he plans to return to China this summer, where he’ll continue to make music.