Who is allowed to report the news in China?

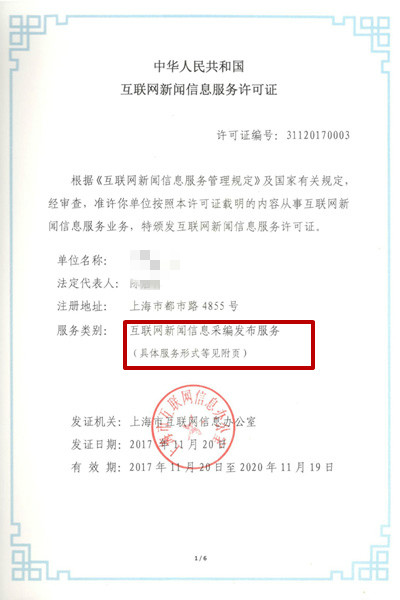

Earlier this month, Shanghai-based Q Daily was ordered to halt producing works of original journalism because it lacked the necessary state-issued “online news and information service” permit. What are these permits, and how are they obtained?

Illustration by Hannah Bae and Adam Oelsner / @eatdrinkdraw

On July 13, an online publication popular among youth in China, Shanghai-based Q Daily 好奇心日报, was ordered to stop original news reporting. The Shanghai Internet Information Office released an announcement accusing Q Daily of breaking the law by “conducting original reporting” and translating foreign press coverage of current affairs. Administrative punishments would be imposed in accordance with the law, the announcement said, though the exact punishment wasn’t specified.

Q Daily isn’t the first outlet to be penalized for trying to do honest journalism. All major online news portals in China, including Tencent, Sina, NetEase, and Phoenix New Media (iFeng), were fined for news reporting in mid-2016, and have been slapped with sporadic violations ever since. In an age where self-media (自媒体 zì méitǐ) — referring to independent, often small media outlets — dominate the landscape, the question is: Who has the authority to actually report the news?

Permit required

As outlined under the Provisions for the Administration of Internet Information Service — a document first published in 2005, then updated in May 2017 — websites, apps, forums, blogs, microblogs, public WeChat accounts, instant messaging services, and all platforms for internet livestream or media must hold a permit in order to “offer online news and information service” (提供互联网新闻信息服务 tígōng hùliánwǎng xīnwén xìnxī fúwù).

There are three types of permits, according to the provisions:

1. Editing and publishing services

采编发布服务 (cǎibiān fābù fúwù)

Required for original reportage. As explicated in this document via the Cyberspace Administration of China: “Editing and publishing services refers to services for the collection, editing, production, and publishing of news information” (采编发布服务,是指对新闻信息进行采集、编辑、制作并发布的服务 cǎibiān fābù fúwù, shì zhǐ duì xīnwén xìnxī jìnxíng cǎijí, biānjí, zhìzuò bìng fābù de fúwù).

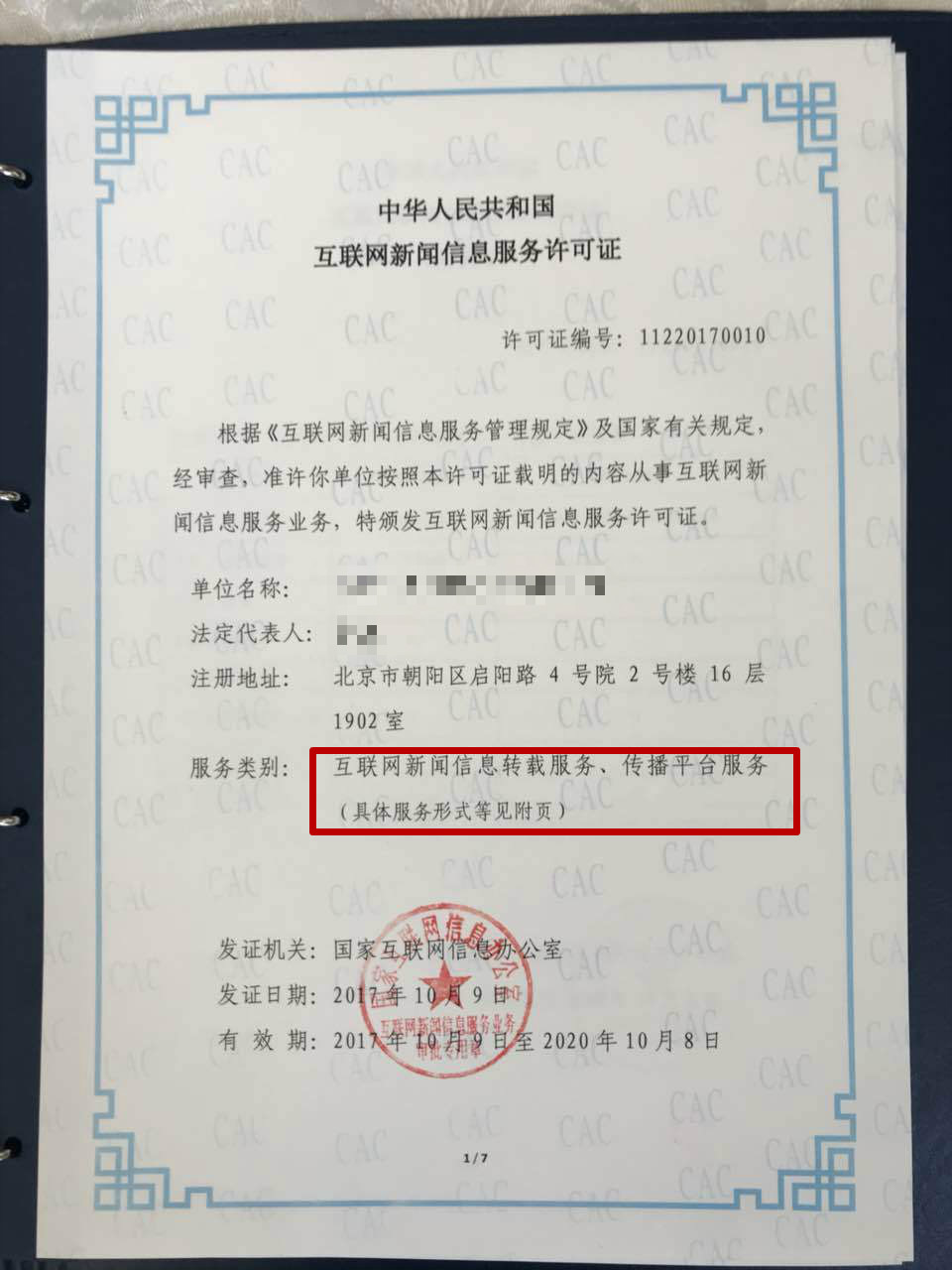

2. Forwarding and reposting

转载服务 (zhuǎnzǎi fúwù)

In other words, news aggregation. Commercial news portals including Sina, Tencent, Netease, and Phoenix do lots of this: Editors aggregate news stories published by media — media that have a reporting permit — and repost those stories on their websites or apps without changing a single word in the story. In fact, modifying the main body of news stories is one of the biggest no-nos for editors at commercial news portals. Their job is to select stories to aggregate and repost. They’re allowed to do so as long as their organization has a “forwarding and reposting permit.”

3. Information dissemination platform

传播平台服务 (chuánbō píngtái fúwù)

As explicated in the provisions, this permit is aimed at platforms — e.g., Sina Weibo, WeChat, Jinri Toutiao, etc. — in which individual users can create and aggregate content. One of the main reasons for last year’s update of the Provisions for the Administration of Internet Information Service was to keep up with these new media platforms.

Different requirements for different permits

The permit for original reporting is the most difficult to obtain, because the provision states that “non-publicly owned capital may not enter into online news information gathering activities” (非公有资本不得介入互联网新闻信息采编业务 fēi gōngyǒu zīběn bùdé jièrù hùliánwǎng xīnwén xìnxī cǎibiān yèwù).

This essentially means “you can only apply for an original reporting permit when you are within the system (体制内 tĭzhì nèi), under direct control of the party,” according to a person who worked as what is perhaps best described as a “content supervisor” within state-owned media for five years.

While the prohibition of “the entry of non-publicly owned capital” precludes non-state-owned or non-state-holding media outlets from applying for the original reporting permit, the second and third permit types are open to all domestic news outlets. (Foreign organizations are strictly prohibited.)

There are 12 commercial news outlets and internet companies holding the second and third permit types, as listed by the State Internet Information Office. In comparison, 292 news media outlets currently hold an original reporting permit.

But it has to be pointed out that while conducting original reporting without the proper permit is technically against the law, enforcement of that law is selective at best.

“It is important to understand that regulation in Chinese media is like a black box,” the content supervisor said.

It used to be fine, permit or no permit

Before mid-2016, commercial news portals provided original reporting despite the first iteration of the Provisions for the Administration of Internet Information Service having been in effect since 2005. Many experienced journalists left print media in the early 2010s and joined news portals, making online platforms a new arena for journalism after the decline of traditional media.

Some edgy original content from that era still survives today. Thinkerbig, a program founded by Tencent Culture Section in 2013, invited scholars from all fields to discuss current affairs or trendy topics in academia. “Publishing original reports every day, we are dedicated to enhancing interdisciplinary understanding so as to promote social development,” the website states. Some stories from the program are still available on Weibo, including a public intellectual arguing why Japan is unlikely to have a military resurgence, and a scholar discussing how media bias led to the deterioration of Sino-Japanese relations.

But in July 2016 — less than a month after Cyberspace Administration of China director Lu Wei 鲁炜 was replaced by Xu Lin 徐麟, a longtime ally of president Xi Jinping — the Beijing Internet Information Office ordered commercial news portals to close programs dedicated to original news reporting, citing violations of the Provisions for the Administration of Internet Information Service. Sohu, Tencent, and Sina were all affected.

The New York Times reported that many news portals were doing investigative journalism before the ban. It listed two investigative pieces, one by Sina’s News Geek program on chemical contamination at a Beijing school, the other by NetEase’s Landmark program on the arrest of a relative of a jailed former top official.

Among the programs ordered to shut down, some did original reporting on foreign affairs. Global Outlook, a program in the international news section of Sohu, still has most of its original articles online, including translations of foreign coverage. The stories are extremely broad in their scope, from the assassination of Kim Jong-nam to Chinese students’ name-tags being ripped off at Columbia University. None of these stories were straight-up reproductions of state-owned media reports.

There were a few more rounds of crackdowns on original reporting on commercial news portals in the months afterwards. Phoenix, the most defiant of the platforms, has been identified by the Beijing Internet Information Office for “illegally conducting original reporting” three times since, once in December 2016, another time in March 2017 during the Two Sessions, and a third time in December 2017.

These days, the news sections of commercial media outlets mostly run similar stories on identical topics. The multiple crackdowns have largely worked as intended. In a December 2017 article about the endangered status of investigative journalists in China — only 175 left in the wild, according to research, an almost 50 percent decline from six years prior — the author cited “increased administrative control over reporting on sensitive societal topics” as a principle reason for the profession’s downturn.

Enter short videos and WeChat public accounts

2016 marks the coming-of-age of livestreaming and short videos in China. According to market research, there were around 200 streaming apps and platforms in 2016, with a total number of 325 million users. The short video market experienced exponential growth that same year. Miaopai, the biggest short video service provider, saw a sixfold increase in views in 2016 compared to the previous year, from 340 million to 2.04 billion.

Launched in November 2016, Pear Video is a newcomer to the field, yet quickly became the leader in short news video production. The video it produced on child labor in clothing factories in Jiangsu Province became an internet sensation. Xinhua, People’s Daily, and CCTV all followed the story, and local police stepped in to launch an investigation. At the height of the U.S. presidential election in November 2016, Pear Video was again at the forefront of original news reporting. From interviewing Chinese-American Trump supporters to documenting the life of immigrants at the border, Pear Video sent out more than 400 short videos on the U.S. election, receiving 850 million total views.

Yet three months into its launch, in February 2017, Pear Video received a notice from the Beijing Internet Information Office, which stated that Pear Video, without the “qualification to provide online audio-visual program services,” was “illegally” publishing “so-called scoops” that included original content, edited clips, and aggregated user-uploaded content.

Pear Video later announced that its editorial focus would shift from current affairs and breaking news to young people’s lives, emotions, and thinking, “to tell the China story through personal narratives.”

Just as one is required to have a permit to publish online news, a permit is required to publish short news videos or streaming news events, according to the 2007 Administrative Provisions on Internet Audio-Visual Program Service. Again, the provision stipulates that only state-owned (国有独资 guóyǒu dúzī) or state-holding enterprises (国有控股 guóyǒu kònggǔ) can apply for the permit.

But where do WeChat public accounts fall? Though the majority of the 3.5 million WeChat public accounts do not have a permit to publish online news or audio-visual information, they still publish current affairs and commentaries on a regular basis.

Zhanhao 占豪, an individual-owned WeChat public account dedicated to print commentary on current affairs, has more views than Xinhua Net’s (新华网 xīnhuá wǎng) public account, according to New Rank, one of China’s earliest and most authoritative data monitoring sites of self-media. (Xinhua Net is the official website of the Xinhua News Agency 新华社.) Among the Top 10 highest-ranking WeChat public accounts under the news category, Zhanhao is the only one not affiliated with a government institution. Yet so far it has not been targeted for reporting without a permit.

“For WeChat public accounts, the state largely chooses to be reactive,” argues the content supervisor with experience within state media. “As long as you don’t touch on taboo matters, no one will target you for reporting without a permit.”

Moreover, individual-owned WeChat public accounts are principally regulated and managed by the platform, not by the State Internet Information Office, as China Communications University Professor Wang Sixin noted in an interview with Hong Xing News. This means that the responsibility for making sure WeChat public accounts don’t publish anything that “goes against the interest of the state” falls upon the platform. Enforced self-censorship, basically.

From November 2017, Tencent began publishing a weekly list of WeChat public accounts that were shut down. One reason given for an account’s closure is “publishing news in violation of rules” (违规发布新闻信息 wéiguī fābù xīnwén xìnxī). The latest Tencent announcement shows that from July 6 to 12, the platform closed 1,233 public accounts — though how many were for “publishing news in violation of rules” is unspecified.

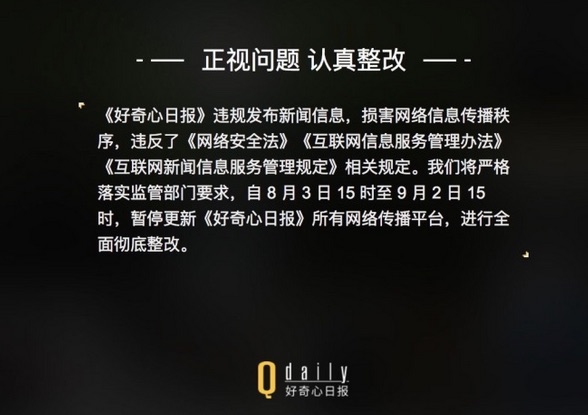

Q Daily, since its establishment, is known for its courage in covering issues ignored by mainstream Chinese-language media, from Beijing migrant worker evictions to the deletion of posts from Chinese social media. Yet this is reportedly the first time since its founding in 2014 that Q Daily has been ordered to scale back its original reporting.

On July 13, Q Daily published a short post on its website acknowledging that it received a warning from the Shanghai Internet Information Office regarding reporting on current affairs. “Q Daily’s reporting on business, the city, culture, and lifestyle has not been affected,” it said.

UDPATE: On August 3, Q Daily published an announcement stating that updates to all media platforms would be halted for a month, from 3 pm on August 3 until 3 pm on September 2. The announcement cited the reason as “publishing news in violation of rules and breaking the order of online news distribution.”

Q Daily’s website and app are showing complete blank pages as of this moment.