‘It is remarkable to see people so resilient’ — An Ping and the class of ‘77

Q&A with An Ping, among the students who tested into the first university classes after the Cultural Revolution

In 1966, the Cultural Revolution began with a bloody August in Beijing. The national college entrance exam (高考 gāokǎo) was suspended, and although some universities remained open, they were in chaos and nobody was teaching or learning anything as Red Guards rampaged through China. No one in this test-obsessed nation would take another university entrance exam until Chairman Mao was dead and the Gang of Four behind bars.

In October 1977, Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 oversaw the first nationwide university entrance examination since 1965. Applicants could be as young as 13 or as old as 37. This allowed the generation called lǎo sānjiè 老三届 — those who graduated from high school in 1966, ’67, and ’68 and therefore had no chance to go to university — to apply. But they had to compete against the most diligent, most ambitious students from all across China.

Nearly six million people took the two-day exam in December 1977. Only 273,000 of them were admitted to university, less than five percent of all applicants. Compare that to today: According to the Ministry of Education (in Chinese), as of May 2017, there were more than 20 million students enrolled at 2,914 colleges and universities in China.

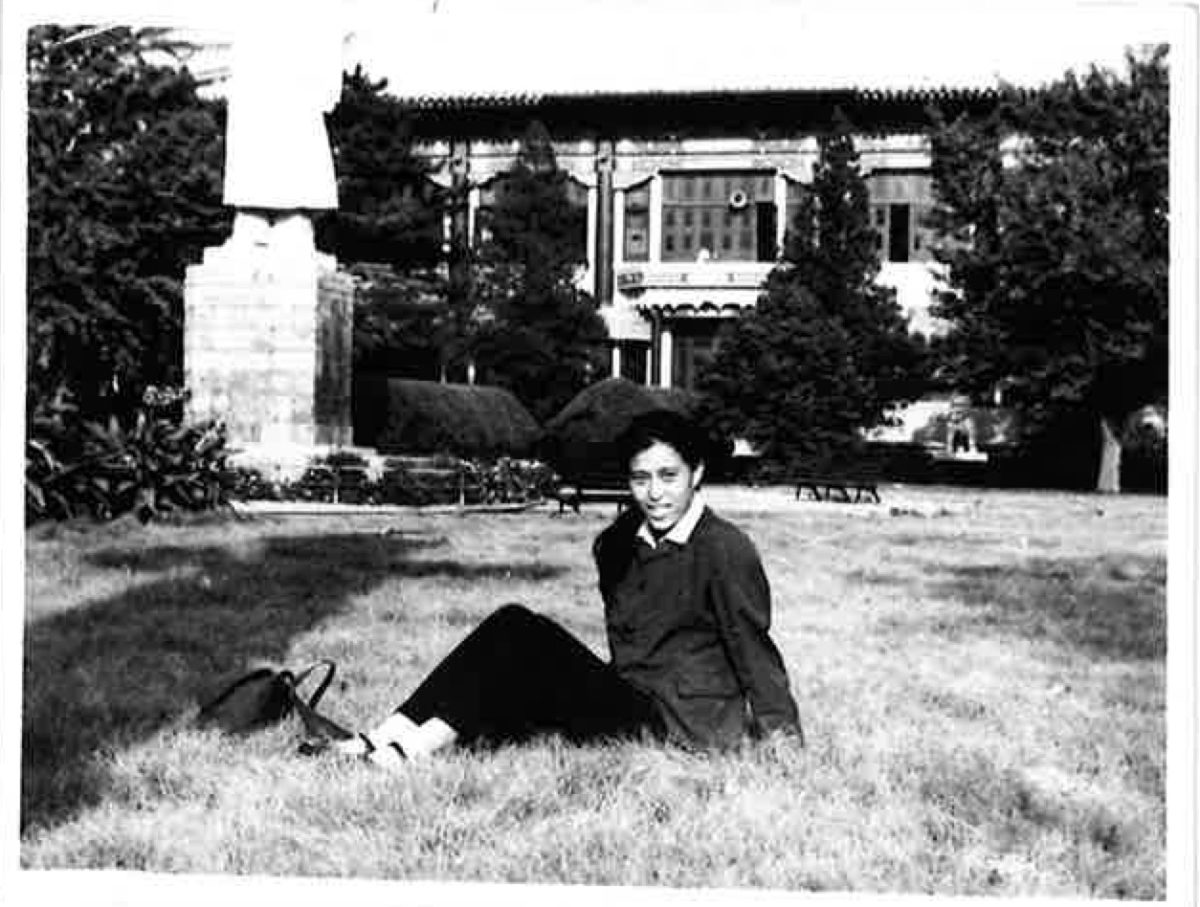

Back in the late 1970s, being a university student was something special. The people who tested into college in 1977 were the rock stars of a country coming out of 10 years of grinding poverty, isolation, and political madness, and they were hungry for knowledge. In China they’re called 77级 qīqī jí — the 77ers, or entering class of ’77. Many of them went on to play key roles in business, academia, the arts, and politics during China’s early opening up period.

Some became the first translators, literally and figuratively, of a China that had been almost completely unknown to the outside world for more than decade. One such 77er is An Ping 安平, who has had a remarkable career as a journalist, as a marketer of jet planes to China, and most recently as organizer of a program that has taken dozens of influential American journalists to China for the first time.

An Ping recently answered some questions by email. An abridged transcript of our conversation is below.

Jeremy Goldkorn: You were in the first class admitted to university after the Cultural Revolution in 1977, the 77ers, and later studied French at the Beijing Language Institute. How many people were in your class, and what other languages were students learning?

An Ping: Beijing Language Institute is not a typical college. It was relatively small and created for foreigners to learn the Chinese language before going to other Chinese colleges in China, and for Chinese to take intensive foreign language training before going abroad. So there were two sections: the Foreign Language Department for Chinese students and Chinese Language Department for foreign students. My class had less than 20 students. Besides French, Chinese students studied English, German, and Arabic. Foreign students studied Chinese, of course.

JG: Are there community or alumni networks of 77ers that stay in touch?

AP: There’s no official alumni network with my class but I stay in touch informally with some classmates who are now in France, China, and the U.S. We communicate more these days thanks to WeChat.

JG: Some prominent 77ers are Yu Minhong 俞敏洪 of New Oriental Education Group, TCL’s Li Dongsheng 李东生, cinematographer and directors Gu Changwei 顾长卫, Zhang Yimou 张艺谋, and Chen Kaige 陈凯歌, and premier Li Keqiang 李克强. Their careers have all been quite remarkable and they’ve put their mark on Chinese society, culture, business, and politics. You yourself have had an amazing career. What have you all got in common?

AP: Because the ’77 class was the first year China resumed the college entrance exam after a 10-year suspension due to the Cultural Revolution, people under 40 years old who had missed the opportunities during those 10 years could apply. According to one statistic, 5.7 million applicants participated in the test, and only 270,000 were admitted, it was the most competitive one. Because of the huge number and highly competitive situation, it’s understandable that there were so many talented people in 77.

I remember that on the first day of classes we discovered that some students were 40 years old while some were 18. Some were married, some were even parents. They came from a variety of professions.

Of course, people went to college for various reasons, but I would say that one common thing is that all these people kept alive their drive and ambition even in the harsh lives we led during the Cultural Revolution. These people didn’t want to accept government-assigned jobs. They didn’t lose hope of going to college, they didn’t lose their curiosity, they didn’t lose the motivation to change their lives. They held on to their ambitions even after years working as farmers in the countryside or as workers in factories. It is remarkable to see people so resilient.

My own experience was typical of resilient ones in the class of ’77. I was sent down to the countryside after high school in 1975, fortunately not too far from Beijing where my family was. I farmed with peasants, I did not have enough to eat and did hard manual work, I was constantly hungry and tired. I could not bear to think that this would be my life forever. When days were short in the winter and we had long evenings, I continued learning French by listening to French language classes on the radio even though I didn’t know if and when I would go back to Beijing or have any chance at higher education. I just told myself that I should keep studying.

JG: After graduating from Beijing Language Institute, you went on to study at the Sorbonne, right? How long did you stay in France, and what was the focus of your study?

AP: I spent about four years in Paris. Before I left for Paris, I was doing a master’s degree in French literature at the China Academy of Social Sciences, so when I landed in Paris, I decided to continue in this track at the Sorbonne.

JG: You later worked as a journalist. What did you cover?

AP: For a short period I was a freelance correspondent for the Chinese-language Radio France Internationale radio station in Tokyo, where I did basic news reporting and broadcasts before moving to Hong Kong.

From 1993 to 1994, I worked in Hong Kong as an editor for the Chinese version of Forbes (资本家 zīběnjiā), the monthly business magazine. I did feature articles, covered a broad range of topics including infrastructure, the luxury industry (the Cognac and Vendome group), as well as aviation (Air France, Airbus). The editor-in-chief and I usually discussed topics and corporations to write on and then I was on my own to do research and interviewing, after which the editor did a final read. I learned a lot from this job — how to research companies and what questions were important. This experience was invaluable in working with journalists once I became a communications executive at Airbus.

JG: How did you end up working at Airbus?

When I was a journalist at Forbes (Chinese version) in Hong Kong in the mid-’90s, I wrote a profile of Airbus, an European consortium composed of France, Germany, the U.K., and Spain, I was fascinated by this company that had been created to break the American monopoly of civil aircraft manufacture. One day, I interviewed the new Chairman of Airbus China in Hong Kong in French. Impressed by my questions, he decided to hire me to be head of corporate communications for Airbus China. I moved from Hong Kong to Beijing in January 1995. At that time, Boeing, our competitor, was a household name, while Airbus was hardly known; some people thought it was an airport shuttle, for example.

Since Airbus realized that China would be the next big market, they made a strategy to open a second Center in China, after the U.S. I was part of this new big venture. My job was to build the Airbus brand in China. I was lucky as I had total support from Airbus Headquarters in Toulouse, France. I got the budget and hired staff I needed.

To build awareness of Airbus for a market where many people had never taken a plane, we spent two years developing the right messaging. My team built up media and advertising campaigns, we did TV commercials, billboards, and placed newspaper advertising; we took Chinese journalists to visit Airbus; we hosted seminars for Chinese airlines and invested $80 million to build training and customer support facilities. When I left Airbus China in 1999, our staff expanded (from 10 when I joined) to 200 in five years. The number of Airbus planes in service in China has increased 50 times in 20 years.

JG: How did you end up in New York, doing work with Asia Society and Committee of 100?

AP: I got married to my husband, who is an American professor. We had a two-year long-distance relationship and we decided that I would give up my career at Airbus in China and move to New York. A friend sent my resume to Committee of 100. I got an interview, loved C100’s mission, and took the offer.

JG: Can you tell us about the delegations of American journalists you take to China and the aims of the program?

AP: This “Understanding China” program was launched by Committee of 100 in 2007. It grew out of a public opinion study called “Hope and Fear: American and Chinese Attitudes towards Each Other”, which confirmed that “neither the Chinese nor American public believes that their country is accurately portrayed in the other country’s news media,” and that travel, seeing China close-up and fact-finding meetings could help improve mutual understanding. According to that Committee of 100 survey, only 32 percent of U.S. opinion leaders had visited China and of those who visit, 70 percent report changed opinions of the country.

Since 2007, I have been running the “Understanding China” program at both Committee of 100 and Asia Society. I am very grateful to Lulu Wang, Anla Cheng, and Ted Wang for supporting this program over many years. [Disclosure: Anla Cheng is the founder of The China Project.] Thirty-eight American opinion leaders from New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, NPR, PBS, CNN, ABC News, Bloomberg, New Yorker etc. have been on this program.

The goal is very simple. We just want American journalists, commentators, and other media leaders to develop a better-informed, more comprehensive perspective on China’s development and challenges. This will, among other things, enrich media presentation of U.S.-China relations. It will deepen U.S. media coverage of America’s most important bilateral relationship in the global order, indeed the world’s most important bilateral relationship.

Our first criterion for recruiting participants is that they must be influential and reputable but not intimately familiar with China. In fact, many eminent journalists I took have never been to China at all. We usually spend one week in Beijing and Shanghai, meeting Chinese leaders from government, business, NGOs, academia, students, etc. This includes very high-level leaders such as current foreign minister Wang Yi 王毅. Asia Society hosts programs with journalists to debrief them when they return from China.

It’s always gratifying to hear from journalists that this program has had some positive impact on them. One journalist commented: “I brought to China a set of suppositions shaped by years of reporting about the place without really knowing it firsthand. Our observation on this trip, with high school students and government officials, with intellectuals and entrepreneurs, left me challenging some of those preconceptions, or at least thinking them through more carefully.”

After one week in China, they usually say that China is a much more complex country than they had perceived. Contrary to the usual American perception of a monolithic one-party-run society, China has multiple, competing interests and authorities about which it’s impossible to generalize in simple terms. Some participants have even said they got confused in the sense that China, in fact, on the ground, is very different from what they expected, different from they read and hear in the U.S. The “Understanding China” program does seem to achieve its purpose of educating American media leaders and, through them, American public opinion.

JG: These are worrying times for people who want China and the U.S. to have a good relationship. Repression of civil society is worsening in China as Beijing flexes its muscles around the globe, while suspicion of China in the U.S. is growing. How are all these big trends affecting the work you do?

It doesn’t affect my job from day-to-day so far. But I observe there is increasing demand for people from both countries to better understand the other country. This modest-sized “Understanding China” program has a bigger bang-for-the-buck return on investment than many larger projects with the same mission.

At this uncertain time, exchanges and better understanding are more important than ever. We need more people capable of explaining their countries in ways that the other can understand. This requires, by the way, people knowledgeable not only about their own history, but also the other’s history and system, the other’s vocabulary, and what the other doesn’t know about their own country.

This is a long-term cause. The U.S. and China are never going to be easy partners. So there’s good and interesting work to be done.