The 1911 Xinhai Revolution and birth of modern China

When the Qing toppled.

This month’s Kuora columns will be in the subject of modern Chinese history. Take a look at last week’s column on how Deng Xiaoping saved contemporary China. This week, we’ll look at one of Kaiser’s answers originally posted to Quora on February 23, 2011:

What were the causes of the 1911 Chinese Revolution?

Political opposition to the Qing Dynasty, founded in 1644 by Manchu invaders from what is now Northeastern China, had been around in one form or another since the inception of the dynasty. Even after the last claimants to the throne from the deposed Ming Dynasty (AD 1368-1644) had been killed, pockets of resistance remained throughout the long Qing reign, often in underground secret societies in the far southern province of Guangdong, membership in which ordinarily required one to swear an oath to “restore the Ming.” Major anti-Qing uprisings took place from 1674 to 1681 (the Revolt of the Three Feudatories), and from 1850-1863 (the Taiping Rebellion, which resulted in the deaths of some 20 million people).

More proximate causes of the 1911 Revolution, though, date only to the latter part of the 19th century (also called the Xinhai Revolution [辛亥革命 xīnhài gémìng], “Xinhai” being the Chinese year corresponding with 1911). China had been defeated in humiliating wars with the British (the Opium War of 1839-41 and the so-called Second Opium War or Arrow War of 1860); with the French, and with the Japanese (1894-95), resulting in a series of “Unequal Treaties” that ceded land to the industrialized imperialist powers and forced China to open “treaty ports” where foreign powers were granted effective trade monopolies. Early efforts by the Qing to respond to preponderant Western might fell mostly under the rubric of the “Self-Strengthening Movement,” a court-sponsored push that began in the 1860s aimed at enlisting Western technology — steamships, cannon foundries — in order to protect a Chinese “essence.” This approach was proven to be inadequate, especially after clashes with Japan over Chinese suzerainty on the Korean Peninsula led to a war that sent the Chinese Imperial Navy to the bottom of the Sea of Japan. The Treaty of Shimonoseki, which settled the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 — and the ensuing “Scramble for Concessions” during which Chinese intellectuals rightly feared the country was about to be “carved up like a melon” — provoked a real crisis.

Popular reaction to this took the form, in some cases, of xenophobic religious movements like the Boxers (the Righteous and Harmonious Fists), which attacked Western missionaries and rail lines and later besieged, with the Qing court’s backing, the legation quarter in Beijing where Westerners held out famously for 100 days before relief arrived.

China’s scholar-official class took a different approach. In 1898, leading reform-minded officials gained the ear of the emperor and for 100 days that year pushed a far-reaching agenda of reforms that ended calamitously as conservative forces at court, led by the Empress Dowager Cixi (the “Old Buddha” and the real power in court), rallied to drive the reform faction out of power — either out of the country, in the case of the lucky few who fled to Japan, or to the executioner’s block.

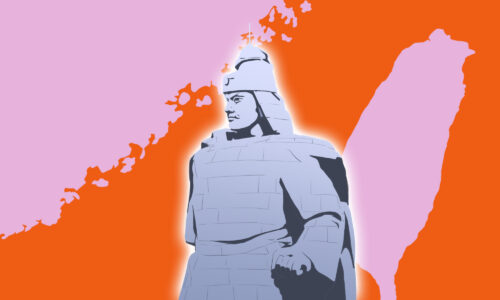

After the defeat of the Boxer Uprising, the Qing court finally began a series of belated reforms. They created a newly organized army, abolished the old Confucian civil service examination system which had been in place since the 2nd century BC, and radically rebuilt China’s education system. But in the meanwhile, opposition to the Qing mounted. Far-reaching as these reforms may have been, they were in retrospect only a last gasp, and proved to be far too little, too late. Sun Yat-sen 孙逸仙 (Sūn Yìxiān) and other (mostly southern) intellectuals, from bases of operation in Japan and in southern China, organized a group called the Tongmenhui 同盟会 (or Alliance Society), the precursor to the Chinese Nationalist Party (the Guomindang 国民党, or Kuomintang). This organization was defiantly anti-Manchu, and called for the creation of a republic. They gained increasing support among intellectuals in China and, most crucially, among young reform-minded officers in the Qing Imperial Army. It was these officers who really touched off the events of October 1911: In fact, Sun Yat-sen himself read about the beginning of the revolution (which broke out in modern Wuhan, Hubei Province) while traveling across the U.S., in a Denver, Colorado hotel.

The Revolution of 1911, though regarded as the birth of modern China (by Nationalists on Taiwan and to a lesser extent in today’s PRC), was really only the first in a series of revolutions that were needed to establish a republic on decidedly wobbly foundations. Victory in this initial revolution, which came with the abdication of the last Manchu emperor in February of 1912, was secured only after a compromise with military strongman Yuan Shikai 袁世凱, who commanded the most powerful modernized Qing forces, and agreed to stop fighting the revolutionaries only after he was promised the “provisional” presidency of the new Republic. Yuan, however, had very different ideas about what the “republic” would look like, and very quickly, a second revolution against Yuan broke out. Before his death in 1916, Yuan actually proclaimed himself emperor — and his was not the only imperial restoration by a warlord in that first tumultuous decade after the Qing collapse.

Kuora is a weekly column.