A porcine predicament for rural North Carolina

DURHAM, NC — In this state, home to 9 million hogs as of January 2018 — and just over 10 million people — one could safely say that we know pork, and know it well. But one large aspect of the pig-farming business here may be on the verge of becoming obsolete knowledge: pork export to China.

In the ever-escalating U.S.-China trade war, exports of pork from North Carolina have dropped dramatically, causing economic pain particularly for the rural, eastern part of the state. A slew of major American agricultural products have been targeted twice this year by China in retaliation for a series of tariffs on a range of Chinese goods. In the pre-trade-war era, China had placed a 12 percent tariff on U.S. pork imports into the country, which already had producers complaining. Then in early April, a 25 percent tax was levied, and following further escalation, an additional 25 percent in July.

The Chinese market represents a unique source of value-added income for products like swine offal (internal organs that are termed “variety meats”), which have much lower demand in North America

China’s tariffs on American pork, along with similar taxes on other agricultural products, have caused such severe pain in specific parts of the American economy that the Trump administration has used a Great Depression-era program to approve up to $12 billion in emergency support to farmers. The first round of payments, including $588 million allocated for the federal government to purchase excess pork, was announced in late August. More subsidies for farmers could be decided by December, officials said.

The American side has dug in, ready to weather a blistering trade war that hits more and more sectors. But the primary one hit so far, agriculture, may already be facing long-term consequences: Han Jun, a vice-minister of the Ministry of Agriculture in China, said in mid-August that the country had “basically stopped” buying American soybeans, adding, “Many countries have the willingness and they totally have the capacity to take over the market share the US is enjoying in China. If other countries become reliable suppliers for China, it will be very difficult for the US to regain the market.”

It isn’t difficult to imagine that pork faces a similar predicament — and, in fact, the Wall Street Journal recently reported that pork producers in places like Spain, Germany, and Chile are all gearing up to establish long-term export relationships with China. Despite the potentially prolonged diminishing of exports to China, President Trump and his administration have signaled again and again that they are intent on “going the whole hog” regarding the bilateral trade relationship with China, increasingly appearing to drive the two countries toward economic decoupling.

North Carolina’s porcine predicament

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce detailed in a June 26 report how U.S. products will be affected by the global response and retaliation to the U.S. tariffs, and in North Carolina, pork ranks among the top exports impacted. Over $100 million worth of both frozen swine meat and offal is exported from North Carolina to China annually. However, individuals in various positions up and down the supply chain are feeling pressured by the tariff war, from exporters to producers.

President Trump and his administration have signaled again and again that they are intent on “going the whole hog” regarding the bilateral trade relationship with China

While China trails Canada and Mexico as the third-largest value market for U.S. pork, constituting over $1 billion nationwide, the Chinese market represents a unique source of value-added income for products like swine offal (internal organs that are termed “variety meats”), which have much lower demand in North America. China is the main consumption market for offal worldwide, so without alternative markets, exporters have no choice but to ride the ebb and flow of Chinese import demand. At the moment, the tide is receding, quickly.

Pork imports into China fluctuate largely depending on the price differences between imported pork and domestic pork. However, “no matter how cheap American pork is, the price gap can be almost eliminated by the additional tariff. This is the reason many Chinese clients have suspended importing USA’s pork currently,” says Angela Zhang, head of the Business Intelligence Division at IQC Insights, a Shanghai-based consultancy that focuses on the pork industry in China.

State export data from the U.S. Census Bureau website shows some pork exports from North Carolina to China plummeting to nearly zero after a sharp uptick in late winter/early spring 2018.

Numbers were already down on exports from North Carolina compared with those in previous years. However, after the onset of trade disputes with China, the volume of some pork export products from North Carolina to China appear to have either plummeted dramatically or stopped entirely.

In recent years, North Carolina has been particularly interested in selling pork to China. Two publications on the website of North Carolina’s Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Doing Business in the U.S. and North Carolina’s Distinctive Advantages, have been translated into Mandarin. Given the lack of any other language translations, this reflects the concerted effort the state has put into courting investment and business from China.

According to a statement released by North Carolina Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler in June, 46,000 full-time jobs are supported by the pork industry alone. Prolonged escalation of tariffs poses a grave threat to the health of the local pork industry, which made up one-fifth of all farm cash receipts in 2016, according to the Annual Statistical Bulletin released by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services and the United States Department of Agriculture.

Smithfield Foods, the largest pork producer in the world, headquartered in neighboring Virginia, was acquired by Chinese meat-processing company WH Group in 2013. The Chinese buyers hoped to meet a voracious appetite for pork among Chinese consumers with pork sourced in large part from places like rural North Carolina.

Now that dream is facing challenges on multiple fronts. Besides the trade war, Smithfield faces an amalgam of environmental and legal pressures after losing a series of nuisance lawsuits filed by more than 500 neighbors of industrial-scale farms under contract. To date, juries have awarded locals in eastern North Carolina more than $500 million in punitive and compensatory damages (reduced to roughly $100 million under a state law that caps payment for nuisance suits).

The Chinese buyers of Smithfield foods in Virginia hoped to meet a voracious appetite for pork among Chinese consumers with pork sourced in large part from places like rural North Carolina. Now that dream is facing challenges on multiple fronts.

Smithfield CEO Kenneth Sullivan spoke with the Wall Street Journal in late May and noted that the outcome of these lawsuits, which are set to continue throughout the rest of 2018, will force the company to “revisit whether we can continue doing business in North Carolina.” WH Group share prices have plummeted 36 percent since the initial announcement of planned, large-scale U.S.-China tariffs in late March. Sullivan said in September that he thought confronting China on trade was “a fight that was necessary,” but that the dispute resolution “isn’t happening as quickly as I’d like it to.”

Help for at least part of Smithfield’s business could come from the most unexpected of sources: the Trump administration. The Washington Post reported on October 23 that the company technically qualifies for part of the federal government’s farm bailout, despite being foreign-owned. But Sullivan remains pessimistic about the future for his pork being shipped to China: On October 26, he went on the record to state that that line of business was no longer viable due to tariffs.

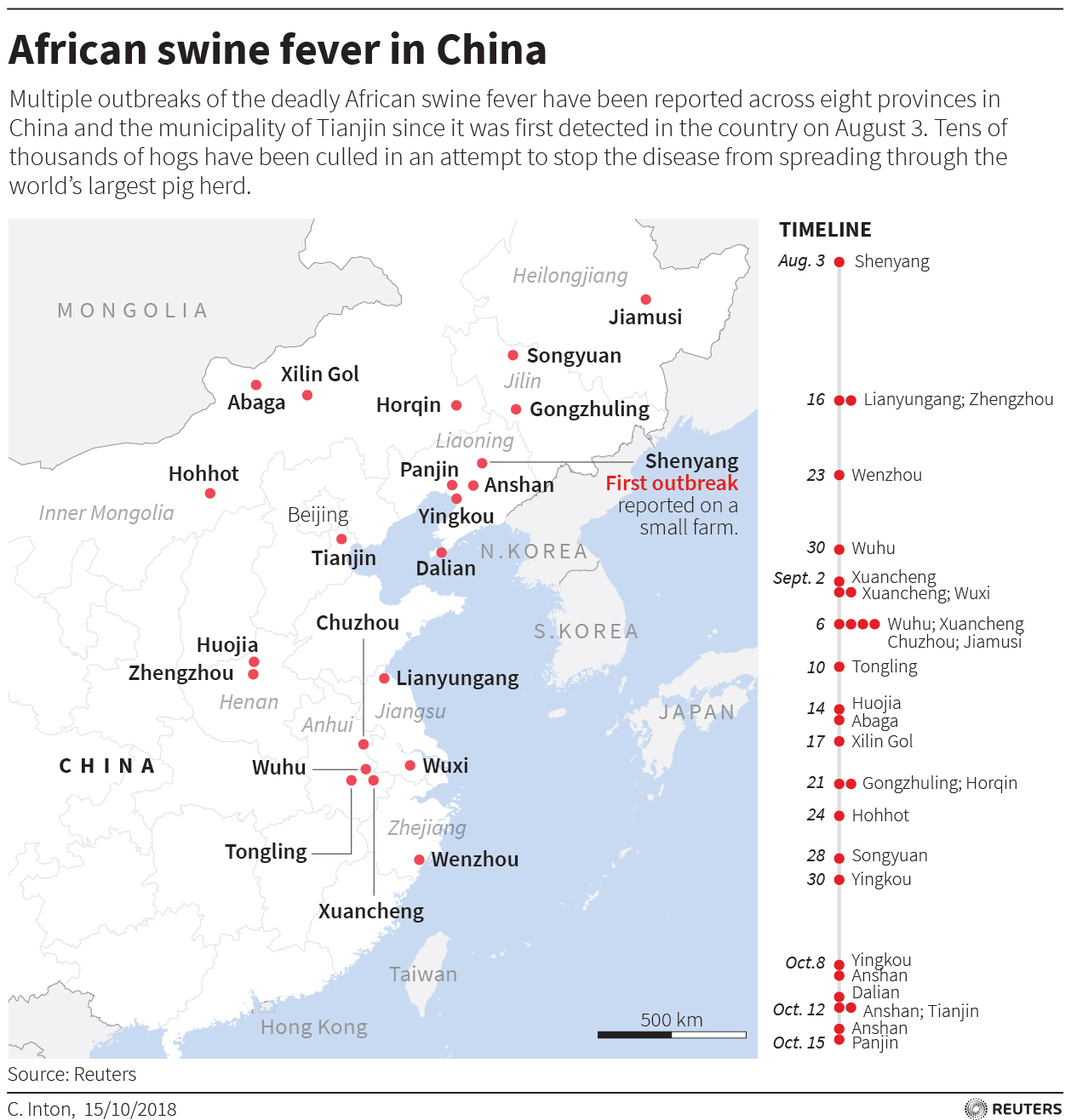

African swine fever

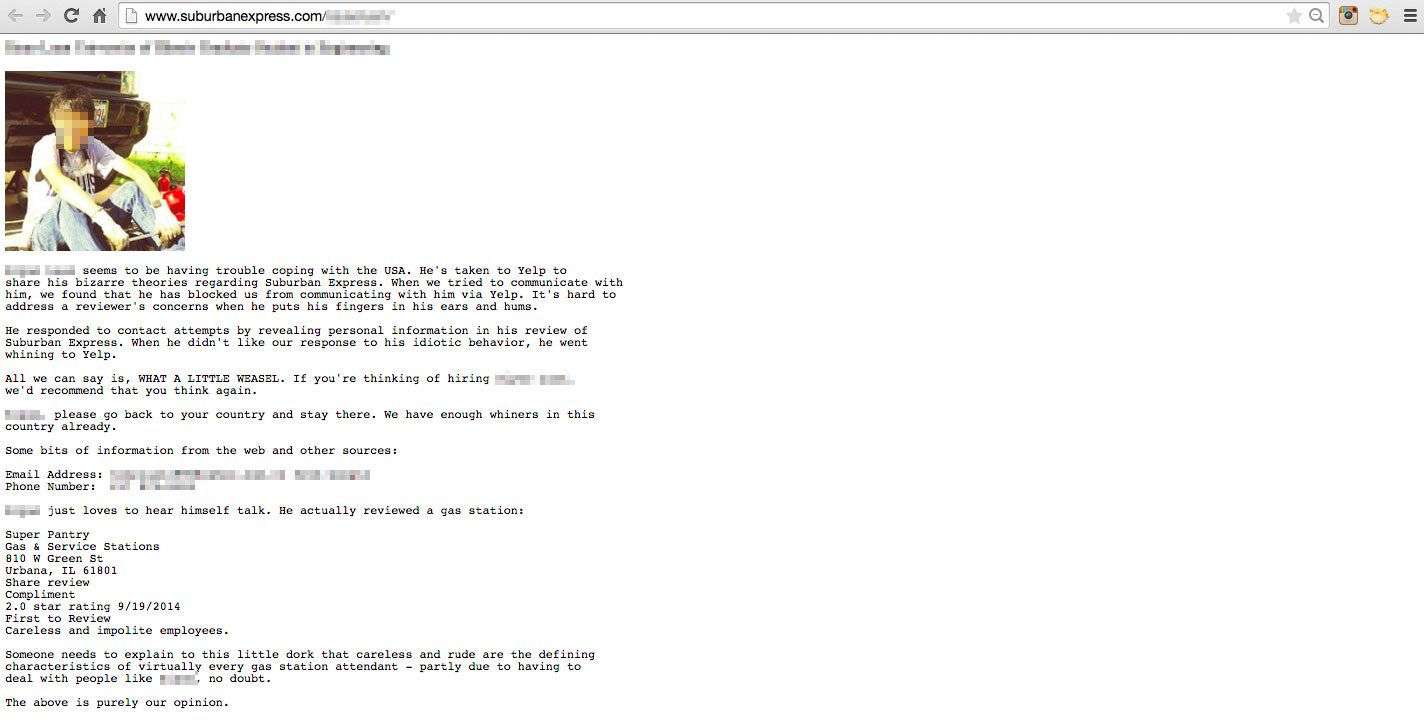

While Americans are being shut out of the Chinese pork market, China’s domestic situation continues to evolve. African swine fever (ASF) was discovered for the first time in East Asia in Heilongjiang Province. Since the initial outbreak on August 3, the virus has spread to over a dozen provinces and municipalities. According to the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, the “virulence and ease of transmission,” as well as China’s “wide geographic distribution,” could “significantly impact China’s swine population and availability of domestically produced pork.” Even as Chinese meat processors fear their stocks may run low due to the disease, they are not turning to the U.S. to alleviate the pressure, but rather to Europe.

The presence of the virus in Henan Province, China’s number two swine-breeding region behind Sichuan Province, could have a significant effect on production for the rest of 2018 and 2019. There is no known cure for ASF, and carriers exhibit up to a 100 percent mortality rate, leaving mass culling of swine as the only dependable method to stymie the spread of the disease.

Dr. Arnon Shimshony, Animal Diseases and Zoonoses Moderator at the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (ProMED), said that this outbreak presents a threat to neighboring countries because of the large distances between infected populations. “Two of China’s thirteen ASF-infected provinces border the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, where — if introduced — will likely remain, with impact onto already fragile rural livelihoods and food security. The disease has spread also to Inner Mongolia, bordering the State of Mongolia. The location of the recent outbreak in Yunnan is very close to neighbouring Asian countries, between 150-300 km from borders of Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand and Laos.”

According to Dr. Shimshony, early eradication odds are “affected by the unfortunate fact that the virus had been circulating on Chinese territory at least two months before being recognized, likely on small holdings in the northeast,” where it was reportedly originally identified in early August. After an outbreak in 1978–79 in southern Brazil, where 224 cases were reported, Brazil did not regain ASF-free status until five years later in 1984.

The spread of ASF across the Chinese pork industry is striking, but not without precedent; independent analyst Simon Quilty of Flinders University in Australia wrote in a report for Beef Central that this outbreak is highly reminiscent of the blue-ear pig disease that struck China in 2008. The language in the report is stark, describing the outbreak of ASF as a “game-changer in global protein supplies for years to come.”

All told, China’s now-monstrous demand for pork may leave no option but to turn to much higher volumes of imported pork. Yet as long as the trade war continues, those importing relationships will be established without Americans involved.