Ningxia to learn from Xinjiang ‘experiences in promoting social stability’

Since China’s mass detention of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang was first documented in detail earlier this year, observers have wondered and worried about where the anti-Islam campaign will end.

A not very comforting signal comes from the Global Times, which reports:

Northwest China’s Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region has signed a cooperation anti-terrorism agreement with Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to learn from the latter’s experiences in promoting social stability.

And this is not the first news of a growing government desire to control Islam in other parts of China beyond Xinjiang, particularly Ningxia Province, where nearly 10 million Hui Muslims live.

- In July, AFP reported, “Communist Party has banned minors under 16 from religious activity or study in Linxia, a deeply Islamic region in western China that had offered a haven of comparative religious freedom for the ethnic Hui Muslims there.” Linxia is in Gansu Province.

- An anonymous senior imam said bluntly to AFP then: “Frankly, I’m very afraid they’re going to implement the Xinjiang model here.”

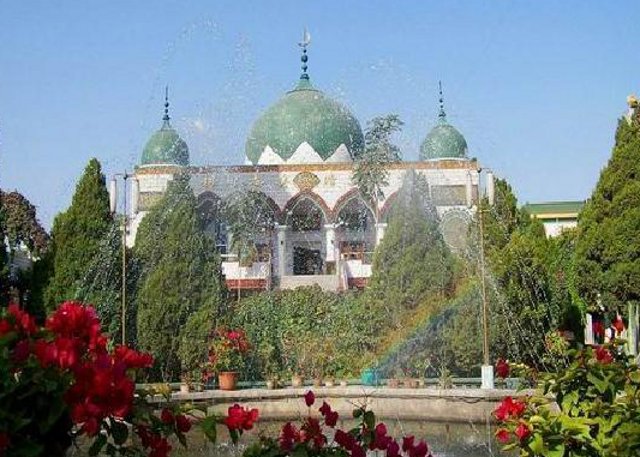

- In August, a plan to demolish the Weizhou Grand Mosque in Ningxia was protested by thousands of Hui Muslims for three days. The protests worked and plans were halted, but authorities appeared to still be keen on at least removing eight of the mosque’s nine onion-shaped domes, to reduce the “Arab style” of the building.

- In September, authorities renamed a river in Ningxia from the Arabic-sounding “Àiyī 爱伊” to “Diǎnnóng 典农” with no community consultation, to have it “better reflect Chinese culture.”

- Yesterday, November 27, the Hui Muslim freelance writer Ismaelan tweeted, “Police take me go,” adding no further details.

Update:

Muslim activist @ismaelan reappears online with a transcript of his interrogation after tweeting about being taken away by police. They seem very interested in what he says on Twitter — a point of emphasis for Chinese security forces recently. https://t.co/EwBo03mb7l

— Josh Chin (@joshchin) November 29, 2018

Beijing has become increasingly defensive about its political education internment facilities in Xinjiang. Most recently, Chinese ambassador to the U.S. Cuī Tiānkǎi 崔天凯 told Reuters that the facilities are targeted at terrorists, and aim to “re-educate” them and “turn them into normal persons,” and he threatened unspecified retaliation against the U.S. should Washington impose sanctions.

James Leibold, an expert on ethnic policy in China, writes in the New York Times (porous paywall) that the camps are instead targeted broadly at Uyghurs for this reason:

In Chinese thought, humans are not equally endowed; they vary in suzhi (素质 sùzhì), or quality. A poor Uighur farmer in southern Xinjiang, for example, sits at the bottom of the evolutionary ladder; an official from the ethnic Han majority is toward the top.

But Communist ideology holds that “individuals are malleable,” so “even a lowly Uighur farmer can improve her suzhi — through education, training, physical fitness or, perhaps, migration.”

Leibold writes that the type of extreme “re-education” ongoing in Xinjiang usually “elicits a mix of emotions. Some subjects comply, others withdraw; a few may even be enthusiastic at first. But over time the suffocating nature of repression also tends to breed resentment and resistance, and those in turn can bring about even more repressive methods of control.”

Other recent notable Xinjiang-related links:

- New exclusive video: Another “transformation through education” camp for Uyghurs exposed in Xinjiang / Bitter Winter

The inside of a recently built “vocational training center” looks exactly like a prison, and very little like a school. Dormitory rooms with locks can hold a dozen or more people, all windows are double-barred, and entrances and exits are each topped by three surveillance cameras. - Woman describes torture, beatings in Chinese detention camp / AP

- Lu Guang: Award-winning Chinese photographer disappears in Xinjiang / BBC

- Statement by concerned scholars on China’s mass detention of Turkic minorities

Correction: The July AFP story cited is about Hui Muslims in Gansu Province, not Ningxia.