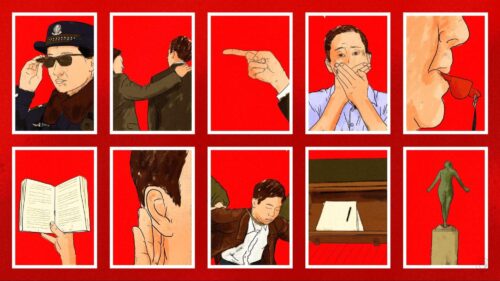

Kuora: Breaking the Great Firewall

This week’s column comes from one of Kaiser’s answers originally posted to Quora on January 12, 2015.

Can’t hackers around the world unite to break the Chinese GFW and free the people in China? Where are the heroes?

This question supposes incorrectly that the main problem of censorship is the inability to access sites outside of China, which actually almost any intelligent Chinese person with a networked device can get to at little or no cost through the use of numerous widely available circumvention technologies. Access to many such technologies is not itself prevented by the Great Firewall of China. Look at the great number of VPN apps available just on the Chinese iTunes Store if you don’t believe me. [UPDATE: How things have changed — many of these apps have vanished in the last two years.]

Having access to Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and the New York Times (to say nothing of The China Project!) would not “free the people in China.” Not when there’s so much censorship of websites hosted within China, carried out not by some automated and central system but rather by the internet companies themselves, on orders from the government. Once a post is deleted from, say, Weibo, it’s pretty much gone. Sure, one could set up mirroring sites that preserve posts even after they’re removed, and some organizations have set up such mirroring sites, but for the most part Chinese users of social media are not apt to find and use those.

China has internet services that fulfill the needs of many of their users: tremendously good ecommerce services, massive social networks (where all their friends are, anyway), chat apps, search engines, you name it. Such services will of course be inadequate for people who want to engage on political topics or other things that the government actively censors — Tibet or Xinjiang independence, historical events like the Tiananmen Square demonstrations of 1989, Taiwan independence, the Falun Gong religious sect (which Beijing regards as a cult, an opinion shared by many who are otherwise very critical of Beijing) — or for people who want to use the internet to organize political opposition. Even if you believe that the rights of such people to speak on, read about, and share such things ought to be protected — and many people within China certainly feel that way — the fact is that most people aren’t that interested in those things, and don’t feel all that frustrated by the fact of censorship.

Ironically, it’s this very idea that “heroes” can “free the people of China” through the internet that really prompts the Chinese government to believe that internet censorship is necessary. When the people most critical of Beijing, most apt (in Beijing’s eyes) to want to sow discord and create social instability, who most want to bring about “regime change” or the collapse of the Chinese Communist Party — when those people are the ones calling most loudly for internet freedom, naturally they’ll provoke even greater hostility to the idea of an uncensored internet. If every one of the Chinese Communist Party’s perceived enemies shouted that aluminum foil was the way to bring them down, and encouraged everyone to find ways to bring aluminum foil into China, you can safely assume that the CCP would crack down hard on aluminum foil.

Kuora is a weekly column.