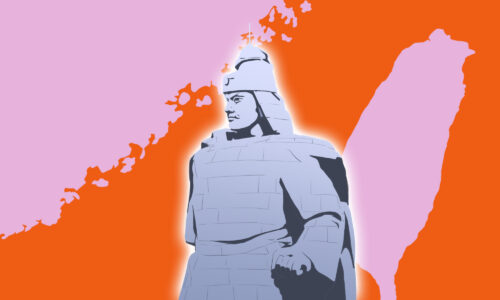

Lost Province: China’s Xikang, now Tibet and Sichuan, is turning 80. But few people realize it ever existed

The people of Xikang’s central region were known as Khampas until the Chinese Communist Party officially recategorized them as Tibetans after 1949. But before Xikang would be relegated to the footnotes of history, it was a fascinating place, one of experimental programs, rapid development, and even a brief war between the Dalai Lama and a warlord of Sichuan.

January 1, 2019 marks the 80th anniversary of a milestone that changed the map of China in perpetuity: On this day in 1939, the Republic of China declared the founding of a “Xikang Province” at the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Its borders encircled a Tibetan-speaking region known locally as Kham, or 康 (kāng) in Chinese. Although few people alive today are aware that Xikang ever existed, it had an indelible impact on ethnic relations in the PRC. The emergence of Xikang Province is a fascinating story involving inter-ethnic warfare, warlord politics, and the Japanese invasion of China.

It began with an assassination. In 1905, an official of the Chinese empire named Fengquan was stationed deep within the Kham region when he raised the ire of indigenous residents, known as Khampas, by implementing a program of agricultural colonization in spite of their protests. After a mob ambushed and murdered him at a point known as the “Parrot’s Beak,” the Governor General of China’s neighboring Sichuan Province responded by sending in a conquering army under one Zhao Erfeng 赵尔丰. Zhao led a sweeping military campaign that overthrew indigenous rulers throughout the region and converted their domains into Chinese-style counties. In 1911, Zhao’s successor, Fu Songmu 傅嵩沐, sent the Qing court a detailed proposal for converting Kham into a Chinese province.

“The land of old Kham is in the west,” explained the proposal, “so its name is called Xikang Province” — 西康 (xīkāng), literally “West Kham.”

Then China had a revolution. The Revolution of 1911 saw Zhao beheaded and Fu imprisoned under the authority of the new governor of Sichuan Province. Their province-building project was effectively dead. At the request of his captor, Fu wrote a book about his failed endeavor. This book, titled Record of Establishing Xikang Province, went to press in serialized form in 1912. For a long time, that was that — warlords vied for control of Kham, but the central government in Nanjing, controlled by the Nationalist Party, paid little notice.

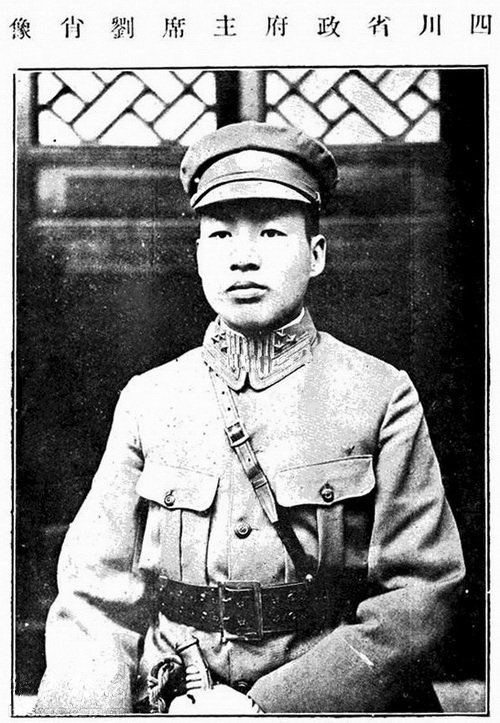

That all changed in the tumultuous 1930s. First, the dominant warlord in Sichuan, Liu Wenhui 刘文辉, found himself drawn into a war with the Dalai Lama of Tibet over control of Kham. When Liu returned victorious to the Sichuanese capital of Chengdu, he was ousted by his nephew and had little choice but to retreat with his army to the foothills of the Kham region. Having lost control of his home province, Liu pondered Fu Songmu’s old dream of turning Kham into a Chinese province: might Liu be the one to finally make it happen?

It would not be a simple undertaking. The central government consented to Liu’s aspirations but offered no real assistance. And there was resistance within Kham. Liu Wenhui’s presence in the region provoked a “Khampa rule for Kham” movement that ended in armed clashes between Khampa rebels and Han Chinese forces. Liu established himself as the supreme Chinese authority over the region, but not before he suppressed two major uprisings by dissidents within the Nationalist Party.

The final push to create Xikang Province came from forces beyond Liu’s control: When Japan invaded China’s eastern seaboard in 1937, the central government fled from Nanjing to a temporary base in Sichuan Province. With Kham practically next door, the Nationalist government was finally eager to negotiate with Liu over the establishment of his province.

In 1938, the Chinese press broke the news that the creation of a new Chinese province was imminent. So did the international press — for example, the Christian Science Monitor reported that “government heads at Chungking have decided that with the New Year, Sikang…will be a new province and given full recognition for its role as site of vast land-reclamation projects which are to be pushed by both Government and semiofficial circles.” On January 1, 1939, Liu Wenhui mounted a stage in the new provincial capital of Kangding to proclaim the founding of Xikang Province. “From this day forth,” he announced, “the process is complete, the borders are clear, and the status of [the province’s] governance, economy, and culture will increasingly be seen as on par with the provinces of the interior.”

For 10 years, Liu worked to develop his mountainous province while the Nationalists and the Communists battled the Japanese and each other. Liu oversaw the creation of boarding schools for Han and Khampa children. He implemented a program of experimental agriculture where scientists worked to improve the efficiency of yak herding and developed high-altitude wheat strains. He even installed a state-of-the-art hydroelectric plant in the provincial capital of Kangding at 9,000 feet above sea level.

By late 1948, word had reached Kangding that the Nationalists were losing badly to the Communists on the faraway battlefields of Manchuria. Liu Wenhui called a meeting of his top officials and told them that “the two provinces of Sichuan and Xikang will become the last battleground in this struggle.” To adapt to the changing situation in the southwest, Liu claimed he must “go to Chengdu and take charge.” Liu then traveled to Chengdu — and defected to the Communists.

Xikang was indeed the very last province to submit to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), months after Mao Zedong declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The PLA carried out an extensive survey of Xikang as they entered, taking notes on the rural economy, religious institutions, local customs, and ethnic relations. They no longer referred to the people of Kham as Khampas, but as “Tibetans” (藏族人 zàngzú rén), officially sorting them into the same ethnic category as their neighbors in Tibet.

Under an entry for policy recommendations, one surveyor wrote that “we must smash the mindsets of Han chauvinism and narrow-mindedness to ‘unite and help one another.’” This statement was an obvious criticism of Nationalist rule, which had prioritized the interests of Han Chinese settlers over Khampa natives, but it was also an implicit criticism of the “Khampa rule for Kham” uprisings, which Chinese leaders had long condemned as “narrow ethnic nationalism.” That same year, in an apparent bid to reduce ethnic tensions, the Communists designated Xikang as the PRC’s first “Tibetan Autonomous Region.”

The name “Xikang” would soon disappear entirely from the political map of China. Now that the Communist Party had reassigned Liu Wenhui away from Kham, the First National People’s Congress in 1955 moved to dissolve his province. Its eastern portion, which had served as the seat of Liu’s government, became the “Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture” (甘孜藏族自治州 gānzī zàngzú zìzhìzhōu) of Sichuan Province, adopting the name Ganzi from one of its counties.

Xikang may be long gone, but its legacy persists in China’s administrative divisions. It was the first “Tibetan autonomous region,” predating the much larger Tibet Autonomous Region (or TAR) by some 15 years. Depending on how you figure it, Ganzi was also the first “ethnic autonomous prefecture,” since it developed out of the 1950 Xikang Tibetan Autonomous Region. Now there are 30 such prefectures.

Today, thousands of Chinese tourists visit Kangding, usually without realizing that it was once the capital of a province. But that may be changing. In 2005, CCTV-1 aired a documentary episode called “A Lost Province” based on found footage of Xikang Province from 1939 and 1944. More recently, Chinese historians have been recovering and publishing huge troves of Xikang-related documents, including a 54-volume set that went to press last May. So it seems unlikely, but worth contemplating: Could Xikang reappear on the map of China some day?